Revised Guantanamo force-feed policy exposed

Al Jazeera’s exclusive publishing of a key Guantanamo prison military document lays bare the brutality of force-feeding.

Guantanamo Bay, Cuba – Hunger striking Guantanamo prisoners who are force-fed a liquid nutritional supplement undergo a brutal and dehumanising medical procedure that requires them to wear masks over their mouths while they sit shackled in a restraint chair for as long as two hours, according to documentation obtained by Al Jazeera. The prisoners remain this way, with a 61cm – or longer – tube snaked through their nostril until a chest X-ray, or a test dose of water, confirms it has reached their stomach.

At the end of the feeding, the prisoner is removed from the restraint chair and placed into a “dry cell” with no running water. A guard then observes the detainee for 45-60 minutes “for any indications of vomiting or attempts to induce vomiting”. If the prisoner vomits he is returned to the restraint chair.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMasked Tunisian police arrest prominent lawyer for media comments

Gaza’s mass graves: Is the truth being uncovered?

Tunisia: The migration trap

That’s just a partial description of the “chair restraint system clinical protocol” which medical personnel are instructed to follow when administering a nutritional supplement to prisoners who have been selected for force-feeding by Guantanamo Commander Rear Admiral John Smith.

Standard operating procedure

The restraint system, published here for the first time, along with the feeding procedures policy, was contained in a newly revised Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for Guantanamo hunger strikers, obtained exclusively by Al Jazeera from United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM), which has oversight of the joint task force that operates the prison.

The 30-page manual contains the most detailed descriptions to date pertaining to the treatment of hunger strikers and prisoners who undergo force-feedings. The SOP replaced a previous SOP issued in 2003 – revised in 2005 – which was declassified several years ago by the Pentagon, albeit with redactions. The new, unredacted policy obtained by Al Jazeera went into effect March 5 – one month after Guantanamo prisoners launched their protest over the inspection of their Qurans.

The procedure appears to have been revised and implemented in order to deal with a mass hunger strike.

“Just as battlefield tactics must change throughout the course of a conflict, the medical responses to GTMO detainees who hunger strike has evolved with time,” says the SOP. “A mass hunger strike was successfully dealt with in [2005] by utilising procedures adopted from the Federal Bureau of Prisons and the approach delineated in this SOP.

“However, the composition of the detainee population, camp infrastructure, and policies has all undergone significant change since the initial version of this SOP… Much of the original instruction has been retained in the form of enclosures. In the event of a mass hunger strike, these enclosures can be utilised as they have proven efficacy under mass hunger strike conditions.”

The SOP notes that there are a number of prisoners who have been hunger striking since 2005, who have “proven their determination”, and whose physical frailty have limited Guantanamo authorities’ “options for intervention”. The document goes on to say, “in the event of a mass hunger strike, isolating hunger striking patients from each other is vital to prevent them from achieving solidarity”.

On April 13, guards staged a predawn raid at the communal camp and isolated more than 100 prisoners into single cells in an attempt to bring an end to the protest.

‘Orwellian’

Leonard Rubenstein, a lawyer at the Center for Public Health and Human Rights at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Heath and the Berman Institute of Bioethics, who reviewed the SOP document for Al Jazeera, said the revised guidelines were troubling because they prohibit doctors and nurses from acting independently and make clear that they are simply “adjuncts of the security apparatus”.

Indeed, the SOP says that in order to effectively manage hunger strikers, a “close partnership” must exist between the Joint Medical Staff and the Joint Detention Group security force. Rubenstein characterised such a srelationship as “Orwellian”.

“It is a very frightening idea that the medical staff is an adjunct of the security force,” Rubenstein said. “The clinical judgment of a doctor or a nurse is basically trumped by this policy and protocol. Doctors are not acting with the kind of professional medical independence [they should]. It’s clear that, notwithstanding references to preservation of detainee health in the policy, the first interest is in ending the protests.”

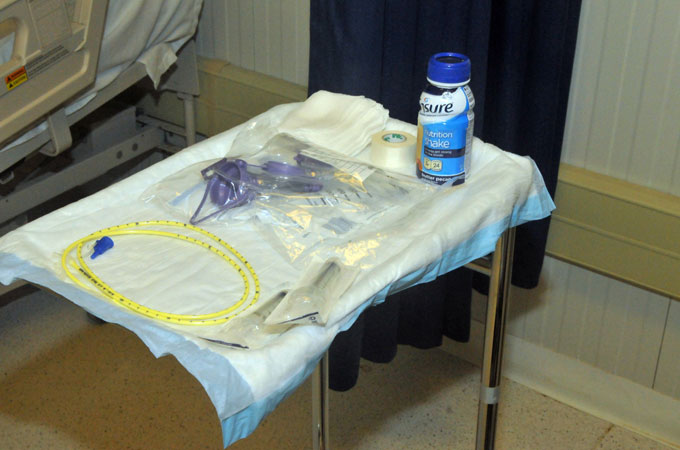

‘Internal nourishment preparation’ supplies in Guantanamo Bay prison, where hunger strikers are being force-fed [Army Sgt Brian Godette]

Rubenstein pointed out the SOP does not provide any direction to medical personnel on how to deal with prisoners who may be suffering from a mental health condition.

Currently there are at least 100 prisoners who are on hunger strike, although some prisoners’ lawyers say that number is much higher.

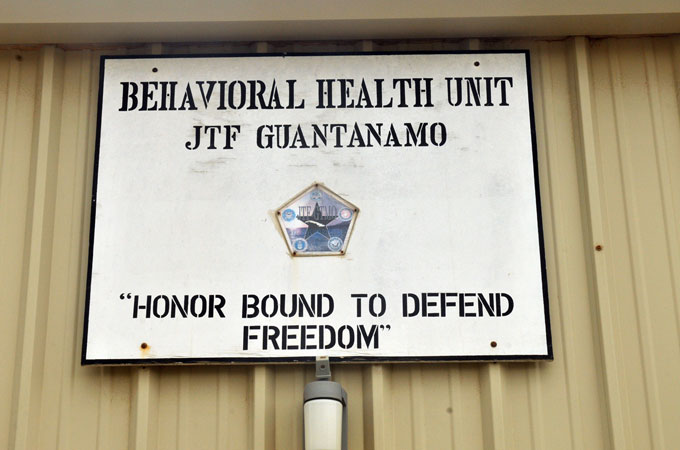

The SOP says the Behavioral Healthcare Service (BHS) “will perform an assessment of the mental and psychological status of the detainee, which will be documented in the outpatient medical record… BHS will continue to regularly evaluate detainees who continue on a hunger strike”.

“What’s missing is the determination of capacity that is required by international ethical guidelines as well as responsiveness to the detainee’s needs,” Rubenstein said.

Prisoners are designated as hunger strikers, according to the guidelines, if they communicate, “either directly or indirectly (ie: repeated meal refusals) his intent to undergo a hunger strike or fast as a form of protest or demand attention”, or if they miss nine consecutive meals and their body weight falls below 85 per cent of either previous or ideal weight – usually calculated using the median BMI for a prisoner’s height.

Final authority

The SOP grants Guantanamo Cmdr Smith – not physicians – the final authority to select hunger-striking prisoners for force-feedings.

Doctors and nurses, who conduct the feeds, are on hand simply to carry out the military’s policy, according to the SOP. Two weeks ago, 40 more nurses were sent to Guantanamo to assist with force-feedings.

“In the event a detainee refrains from eating or drinking to the point where it is determined by the medical assessment that continued fasting will result in a threat to life or seriously jeopardise health, and involuntary feeding is required, no direct action will be taken without the knowledge and written approval of the Commander,” the document says.

Once prisoners are selected for force-feeding, top officials at the Pentagon are notified of “the necessity of initiating involuntary feeding of a detainee”.

Although the manual says medical personnel will make “reasonable efforts” to obtain consent from prisoners designated for force-feeding, it also notes that if consent cannot be obtained “medical procedures that are indicated to preserve health and life shall be implemented without consent from the detainee”.

Rubenstein said the authority granted to Cmdr Smith was concerning because it gives him complete control over a medical procedure that doctors should be responsible for.

In a letter sent to Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel last month, American Medical Association President Dr Jeremy Lazarus said the force-feeding procedure at Guantanamo “violates core ethical values of the medical profession”.

“Every competent patient has the right to refuse medical intervention, including life-sustaining interventions,” Lazarus wrote. “The AMA has long endorsed the World Medical Association Declaration of Tokyo, which is unequivocal on the point: ‘Where a prisoner refuses nourishment and is considered by the physician as capable of forming an unimpaired and rational judgment concerning the consequences of such a voluntary refusal of nourishment, he or she shall not be fed artificially.'”

The United Nations has condemned force-feeding as both a form of torture and a breach of international law.

The revised SOP, however, says the Department of Defense and Joint Task Force-Guantanamo policy “is to protect, preserve, and promote life. This includes any serious adverse health effects and death from hunger strikes”.

Currently, there are 29 prisoners who are being force-fed. Long-term hunger strikers who are force-fed, “are notified by the corpstaff that ‘it is time to feed’.”

Preparing for a mass hunger strike

The new hunger strike policy raises far more legal and ethical questions about the force-feeding process than that issued in 2003 and revised two years later. Pentagon spokesman Lt Col Todd Breasseale told Al Jazeera on March 4 there was nothing questionable about the way in which Guantanamo hunger strikers were treated.

Guantanamo officials, Breasseale said, “follow the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) protocols regarding hunger strike management and involuntary feeding of hunger strikers”.

However, according to a report issued in April by the nonpartisan The Constitution Project, “at least some federal prisons handle hunger strikes very differently, and far less coercively, than at Guantanamo”.

“The written federal guidelines for force-feeding make no mention of restraints, and include several safeguards that are not in place in Guantanamo,” said The Constitution Project, whose members spent two years investigating the treatment of “war on terror” prisoners.

“Prison guidelines require the warden to notify a sentencing judge of involuntary feeding, with an explanation of the background of and reasons for involuntary feeding, as well as videotaping of force-feeding. BOP requires that ‘treatment is to be given in accordance with accepted medical practice’. Accepted medical practice requires an individualised assessment of the patient’s situation that appears to be absent at Guantanamo. It also requires individualised counselling of the detainee…”

The newly revised SOP does not call for that type of counselling. Moreover, according to The Constitution Project, “the BOP’s written policy on the use of restraints also conflicts with the restraint-chair protocol at Guantanamo”.

The United Nations has condemned force-feeding as both a form of torture and a breach of international law [Army Sgt Brian Godette]

The United Nations has condemned force-feeding as both a form of torture and a breach of international law [Army Sgt Brian Godette]

“Federal prisons are known to use restraint chairs for inmates who are physically dangerous to themselves, other inmates, or guards – but at most federal prisons, the chairs are apparently not used for forced feeding,” read The Constitution Project’s report. US prison regulations “make no provision to routine or categorical use in cases, regardless of an individual inmate’s behaviour, or the use of restraints in force-feeding”.

The use of restraint chairs to force-feed Guantanamo prisoners was introduced in 2006 on the recommendation of a forensic psychologist and three Bureau of Prisons consultants who visited GITMO in 2005, following a massive hunger strike. Human rights groups, who say the use of restraint chairs are a form of punishment and an attempt to break hunger strikes, have criticised their use.

Identifying prisoners for force-feeding

The SOP contains a “General Algorithm for a Hunger Strike”, described in the document as “a simplified outline for the medical management of detainees on hunger strike”.

It notes that, after a prisoner is identified as a possible hunger striker, a medical officer performs a physical examination, and the behavioural healthcare service conducts a psychological evaluation. The prisoner is then “counselled” about the dangers associated with a hunger strike.

“If detainee continues to hunger strike and clinical criteria for the initiation of enteral feeding are met… the detainee may be admitted to the Detention Hospital or designated feeding block if medically stable. Authorisation is obtained via chain-of-command from JTF-GTMO Commander to begin enteral feeding.”

Before being placed into the restraint chair, medical personnel offer the prisoner one last chance to eat voluntarily. If the prisoner refuses, the “medical provider signs [the] medical restraint order” to force feed the prisoner, and encourages him to use the restroom before he is shackled.

A guard then “shackles detainee and a mask is placed over the detainee’s mouth to prevent spitting and biting”, states the chair restraint protocol. “Detainee is escorted to the chair restraint system and is appropriately restrained by the guard force.”

A 10 or 12 “French” size (3.3/4mm external diameter) feeding tube is then placed into the prisoner’s stomach through his nostril. He is given a topical anaesthetic, such as viscous lidocaine for his nostril “unless detainee refuses”. A sterile surgical lubricant is applied to the feeding tube.

Medics use a stethoscope and a test dose of 10ml of water to ensure the pipe has reached the detainee’s stomach.

The feeding tube is secured to the prisoner’s nose with tape “and the enteral nutrition and water that has been ordered is started, and flow rate is adjusted according to detainee’s condition and tolerance.”

The manual says a feeding can be “completed comfortably over 20 to 30 minutes”, a claim disputed by Guantanamo prisoner Samir Naji al Hasan Moqbel, who described in a New York Times op-ed the intense pain he experienced from being force-fed.

The administration of two powerful drugs, in addition to a wide range of over-the-counter medication, further undercuts the assertion that force-feeding can be completed comfortably in a half-hour or less. The two drugs at issue, according to the force-feeding policy, are Phenergan, which is used to prevent motion sickness, nausea, vomiting, pain – or as a sedative or sleep aid – and Reglan, which is used to treat heartburn caused by acid reflux. Long-term use of Reglan has been known to cause the irreversible neurological disorder, tardive dyskinesia.

The SOP states that if a prisoner vomits or attempts to induce vomiting after he is placed in a “dry cell” following the “nutrient infusion”, his “participation in the dry cell will be revoked and he will remain in the restraint chair for the entire observation time period during subsequent feedings”.

The manual contains a separate protocol for dealing with prisoners who bite their feeding tubes. That policy also belies claims in the document about the ease of force-feeding a Guantanamo prisoner.

According to the biting protocol, “if the detainee is able to get the [feeding] tube between his teeth, the [registered nurse] shall… direct the guard staff to stabilise the detainee’s head in the midline position… Hold traction on the tube for as long as necessary for the detainee to relax his jaw; then continue safe removal of the tube. This may take considerable time.”

Prisoners are not supposed to remain in restraint chairs for more than two hours.

The size of the tube being used on Fayiz al-Kandari, a Kuwaiti who has been detained at Guantanamo for more than 11 years, is too large and painful, he said through his defense attorney, federal public defender Carlos Warner. Al-Kandari takes force-feedings twice a day through a “10 French” (3.3mm diameter) tube.

“It takes several attempts to get the tube into the right place,” Warner told Al Jazeera. “Once it goes down his throat he has a difficult time breathing. There’s a gag reflex.”

Lt Col Samuel House, a SOUTHCOM spokesman, told Al Jazeera that medical professionals who conduct the force-feedings “carefully evaluate each patient to determine the appropriate size of tube to use”.

“A 10 [French] size feeding tube is tiny,” House said. “It can be used in children as young as six months and is the recommended size for a one-year-old child, according to standard pediatric references. Bottom line: either a 10 or an 8 Nasal Gastric Tube is tiny and should not be a big problem in an adult.”

House added that all prisoners are given a choice at mealtime: “Eat a hot meal, drink the nutrient, or receive an enteral feed.”

Follow Jason Leopold on Twitter: @JasonLeopold