Analysis: Understanding the Sahel drought

Scientists say that the current drought in the Sahel began as far back the 1960s.

Between the vast Sahara Desert and the dense foliage of the African Rainforest is a band of semi-arid grassland. Known as the Sahel, this hardy landscape is one of Africa’s most productive crop regions.

But the crops in the Sahel are grown close to their limits of tolerance, and rely on natural rainfall. This means that even small changes to the amount of rain can have disastrous effects.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAre seed-sowing drones the answer to global deforestation?

Rainfall set to help crews battling wildfire near Canada’s Fort McMurray

The Alabama town living and dying in the shadow of chemical plants

Unfortunately, this is a region which often suffers highly erratic rainfall.

Droughts in the Sahel don’t last a month or a year, they last for decades. And these long droughts have occurred regularly over the past 12,000 years.

The region is in one of these droughts now – scientists say it started in the 1960s.

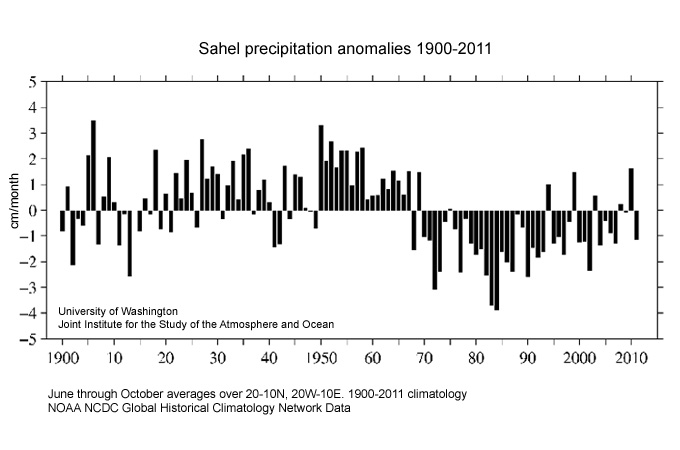

Research by the Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean (JISAO) at the University of Washington shows the amount of rain received each year in the Sahel region, compared with the average. The bars reaching upwards from the centre indicate more rain than average. Those which are drawn downwards, indicate a decrease. Simply, the longer the line, the greater the deviation from the average.

The bars reaching upwards from the centre indicate more rain than average. Those which are drawn downwards, indicate a decrease. Simply, the longer the line, the greater the deviation from the average.

Between the 1950s and 1960s, there was plenty of rain across the Sahel, but just before 1970, a new drought started.

With the exception of a period of five years, all years since have seen a deficiency of rain.

The most severe drought was in the 1980s and, since then, levels of rainfall have recovered a little. However, rainfall remains significantly below the average for the past century.

The rain across the Sahel spreads up from the south during the summer months. The onset is usually in June, with the majority of the rain falling between July and September.

Overall, the amount of rain received in the 2011 monsoon was near normal, but this doesn’t tell the whole story: the rains were patchy and irregular, slow to get going, and retreated very quickly. This left many regions facing water and food shortages.

|

|

Reasons for the drought

Compiling reasons for the drought is difficult, but what is known is that the rainfall across the Sahel is driven by three factors:

- Tropical convection: the huge towering thunderstorms that build quickly in tropical places.

- The West African Monsoon: rains which starts to spread across the Sahel in June.

- El Niño: the effects of the warming of the Pacific, which also affects the weather around the globe.

But there is little understanding of how these factors link together and how they are affected by the changing climate.

In the 1970s it was widely believed that the drought was caused by the farmers in the regions, blaming them for the degradation of the land and the desertification. However, subsequent studies have disproved this idea.

Currently, the most convincing theory is that the recent drought could be due to the change in temperature of the surrounding oceans.

At the end of the 1900s, the south Atlantic and the Indian Ocean warmed quickly, which reduced the difference in temperature between the land and the sea. This may have caused the monsoon to weaken and the thunderstorms to remain to the south.

When the rains do fail, there is concern that this could trigger a knock-on effect in the years to follow.

Less rain means less vegetation, which will lead to a change in colour of the ground. Instead of lush fields of plants colouring the earth in a deep green, which absorbs sunlight, the ground instead would be a lighter, barren beige, which reflects more sunlight.

This, in turn, would mean the temperature difference between the land and the sea was diminished, and would lead to further weakening of the monsoon.

To the future

It is most important to predict what will happen in the future, but currently it is almost impossible.

The difficulty is due mostly to the scant availabilty of historical data from across the region. Therefore, discovering how the climate is changing is an uphill struggle.

The current thought is that the Horn of Africa will become wetter, but what will happen across the Sahel is unknown: will it become wetter or drier? No one can be sure.

What is expected is that the rainfall will become more sporadic, bringing an increase in the number of both droughts and floods across the region.

The 2012 forecast

The monsoon forecast for the Sahel region has just been issued by the African Centre of Meteorological Applications for development (ACMAD). This is the consensus forecast for the region, drawing together forecasts from many different countries.

The forecast focuses on the months of July to September, when the majority of the rain falls across the region.

This year, the forecast suggests that the majority of the Sahel will experience average rainfall, or even above average in some locations.

The exception is the Western Sahel, which is only estimated to receive 70 – 90 per cent of their annual rainfall, and here the onset of the rains is likely to be delayed.

This means that Senegal, southeastern Mauritania, Western Mali and Gambia are all likely to face severe disruptions.

Farmers in these regions are being encouraged to prioritise crops and sow water-stress resistant seeds.

What happens next

Clearly more research is desperately needed – because even small changes in rainfall, both timings and amounts, can have dire impacts on the people who live in the Sahel.

To try to ensure that national governments have access to the best scientific information available, Africa Climate Exchange (Afclix) has recently been launched by a team led by the University of Reading’s Dr Rosalind Cornforth.

Not only does the site help ensure that policy makers have direct access to the latest forecasts, but Afclix helps different research teams with varying expertise connect with each other, enabling collaborations and cross-disciplinary research.

The more studies carried out, the greater the chance there is of discovering the secret of the Sahel rains.

As the knowledge grows, the forecasts will improve and the impacts on the local population can be minimised.

Steff Gaulter is Al Jazeera’s senior meteorologist. Follow her on Twitter: @WeatherSteff