Explainer: How do the elections work?

Convoluted rules mean Egyptians will cast three votes on two ballots over six weeks.

Egyptians will cast three votes on two ballots during the People’s Assembly elections, which begin in November [EPA]

Egyptians will cast three votes on two ballots during the People’s Assembly elections, which begin in November [EPA]During the decades of Hosni Mubarak’s rule, Egypt’s electoral outcomes were pretty predictable: Mubarak was “re-elected” every six years, with 90 per cent of the vote, and parliamentary elections (with the notable exception of 2005) were rigged to ensure a resounding victory for his National Democratic Party.

This year, Egyptian voters will have more than 6,700 candidates to choose from. They represent 47 different political parties, many of which were only established in the nine months since Mubarak’s ouster. Some are grouped into constantly-shifting coalitions.

The vote will be spaced out over six weeks, with different parts of the country voting on different days. The posh Zamalek neighbourhood in Cairo will vote on November 28; residents in Dokki, a few metres across the Nile, will have to wait until December 14.

And voters themselves will cast ballots under two different electoral systems. A resident of the capital’s Raad al-Farag neighbourhood will cast one vote in Cairo’s first district, population 700,000, which has two representatives; and a second vote in a second first district, population 1.25 million, which has 10 MPs.

Confused? Read on.

Dates: A staggered election

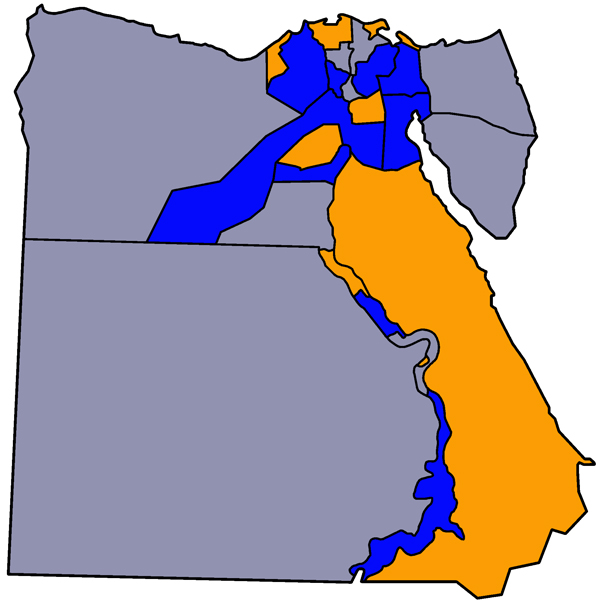

Egypt’s 27 governorates will vote for members of the People’s Assembly in three phases over a period of six weeks, starting on November 28; the governorates are listed below and illustrated at right:

November 28: Cairo, Fayoum, Port Said, Damietta, Alexandria, Kafr Al Sheikh, Assiut, Luxor, and Al Bahar Al Ahmar [the Red Sea].

December 14: Giza, Beni Suef, Minoufia, Al Sharqiya, Ismailia, Suez, Al Bahariya, Sohag and Aswan.

January 3: Al Minya, Al Qalyoubia, Al Gharbiya, Al Dakhalia, North Sinai, South Sinai, Marsa Matrouh, Qena and Al Wadi Al Gadeed [the New Valley].

Run-off elections, as necessary, will be held one week after the initial vote (so December 5, December 21, and January 10).

Elections for the upper house of parliament, the Shura Council, will begin on January 29, with subsequent rounds on February 15 and March 4. A nationwide presidential ballot will follow – in theory, at least – sometime in either March or April.

Representation: Two systems, two maps

The convoluted electoral rules combine elements of both majoritarian and proportional-representation systems.

One-third of the People’s Assembly – 166 MPs – will be elected using a majoritarian system, in which each district is assigned two representatives. Candidates running for these seats can be members of political parties, or they can be independents.

Each voter will choose two majoritarian candidates, and the two which win an absolute majority of votes will be seated. If two candidates do not win majorities, a runoff election will be held.

The other two-thirds will be elected using party-list proportional representation. Districts will be allotted between 4 and 12 MPs under this system. Egyptians will then vote for lists put forth by parties or alliances (such as the Muslim Brotherhood-led Democratic Alliance). The lists are “closed,” which means voters cannot influence their ordering.

These lists will win seats according to their share of the vote: If the Democratic Alliance wins 50 per cent of the vote in a district with 10 seats, then the first five candidates on its lists will be seated in parliament.

So in Cairo, for example, voters will elect a total of 54 parliamentarians. For the majoritarian system, Cairo has been divided into nine districts, which will elect a total of 18 candidates. Under the proportional system, Cairo has just four districts, which have 36 seats between them.

Quotas: Workers, no women

Egypt’s electoral law reserves 50 per cent of seats in the People’s Assembly for “workers and farmers”.

This creates a scenario in which a candidate could win a majority of votes but still lose the election. Consider these hypothetical results from a majoritarian district with 100,000 voters; each may choose two candidates, so they will cast a total of 200,000 votes.

| Candidate | Status | Votes | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hosni Mubarak | Professional | 80,000 | 80% |

| Omar Suleiman | Professional | 65,000 | 65% |

| Ahmed Ezz | Worker/Farmer | 35,000 | 35% |

| Safwat el-Sharif | Worker/Farmer | 20,000 | 20% |

In this scenario, Mubarak would win a seat, because he won the largest majority of votes. But Suleiman would not, despite also winning a majority, because one seat is reserved for a worker/farmer; so Suleiman would be disqualified, and voters would choose between Ezz and el-Sharif in a runoff ballot the following week.

The quota rules are far more cumbersome in proportional districts, but in essence they require smaller parties to elevate worker/farmer candidates in order to ensure the 50 per cent balance.

During Egypt’s last round of parliamentary elections, in 2010, sixty-four seats were reserved for female candidates. That quota has been cancelled; lists are required to field at least one female candidate, but her name can be placed anywhere on the list.

Candidates: Complicated strategy

Candidates are not allowed to run under both systems – to have their names on party lists and simultaneously compete for majoritarian seats. This creates a very complicated calculus for party bosses (independent candidates have an easier time, because they’re only allowed to run in the majoritarian system).

A candidate with strong name recognition might fare better in the majoritarian system, because his name appears directly on the ballot.

But the proportional system offers a better chance of victory – as many as 12 seats, in some districts, as opposed to just two, one of which is reserved for a worker/farmer. Minority candidates like Copts, in particular, will probably fare better at the top of a list rather than running as independents.

Dozens of the so-called felool, the remnants of Mubarak’s now-defunct National Democratic Party, are expected to run for office as independents under the majoritarian system.

There is no prohibition against candidates running for the People’s Assembly and the Shura Council, so election officials say “dozens” of candidates are registered to run for both.