Can Turkey’s secularists defeat Erdogan?

Long an ineffectual opposition party, the CHP may now have a chance to chip away at AKP’s political monopoly.

The state crisis in Turkey is deepening. According to Burhan Kuzu, a Justice and Development Party (AKP) deputy from Istanbul, the National Intelligence Agency (MIT) recently submitted a list to Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan containing the names of 2,000 Gulenist (followers of the self-exiled Islamic leader Fethullah Gulen) prosecutors, judges, police officers and bureaucrats who allegedly formed a “parallel state structure”, and treacherously plotted against their national government in collaboration with foreign agents and the “interest-rate lobby”.

Where are the secularists?

To derail the on-going graft probe, which started on December 17, 2013, and punish those involved in the investigation, the government launched a massive purge operation against the “parallel state”, and sacked or reassigned hundreds of prosecutors, police chiefs and officers across the country. The government also issued a new Judicial Police Decree to prevent prosecutors and police from bringing additional corruption charges against Erdogan himself and his son, Bilal. These executive branch interventions into the judicial branch have been so controversial that even Cemil Cicek, Speaker of the Parliament and a prominent figure within Erdogan’s AKP said that the interventions had gone too far, and effectively declared Article 138 of the Constitution which deals with judicial independence, dead.

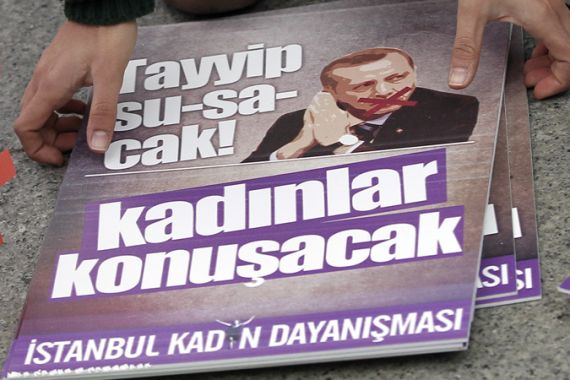

As both AKP members and the Gulenists openly acknowledge it, the power struggle between the two has now turned into a brutal war. While the Turkey’s Islamists are busy with discrediting and destroying one another, what are Turkish secularists doing? Will they declare the enemy of their enemy a friend and ally themselves with the Gulenists against Erdogan? And will that be a smart move?

|

Secularists have long viewed political Islam and its representatives as the greatest threat to the secular regime and the republican ideals and principles known as Kemalism |

It is difficult to talk about Turkish secularists as a monolithic sociological or political category. However, in the common usage, the label “secularist” is often used to refer to the old Kemalist establishment which mainly includes the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the military, and the judiciary (before they were pacified by the AKP-Gulenists coalition) as well as like-minded supporters in the bureaucracy, academia and the media.

Secularists have long viewed political Islam and its representatives as the greatest threat to the secular regime and the republican ideals and principles known as Kemalism. The branch of political Islam established by Necmettin Erbakan – known as Milli Gorus (National Outlook) – especially, has been regarded as the most dangerous stream by both the military and its secularist allies in the political establishment. In order to contain and challenge the ever-growing power and influence of Milli Gorus (and gain access to conservative votes), the secularists have expediently allied themselves with various religious groups and movements in the society.

One of those groups has been Gulen’s Hizmet Movement. In other words, in the past, secularists had adopted a pragmatic approach in their dealings with Islamist groups, and often exploited ideological, institutional and theological differences among Islamists to play them off against one another, and gain political advantage. Given the history and the current state of relations between AKP and the Gulenists, some secularists – especially CHP and its supporters – may be tempted to try to benefit from the situation by seeking an alliance with the Gulenists in hopes of further weakening Erdogan and making modest gains in the municipal elections scheduled for March 30.

Strange bedfellows?

2013 was the most challenging year of Erdogan’s 10-year rule. Two events in particular – the Gezi Park protests, and the December 17 graft probe – have tarnished Erdogan’s image and started his political descent. Even though it has been the main opposition party for more than a decade, CHP has not been able to give Erdogan even a fraction of the trouble that these two events did in a matter of days.

In recent years, CHP’s electoral performance has been abysmal. It has lost every single local and national election since 2002. Many Turks have come to view the party as the eternal opposition party and unfit to rule. One may speculate that this view is largely shared by the party elite who, over the years, have grown increasingly comfortable with their opposition role – albeit an ineffective one – as well. Against this background, one may say that the war between AKP and the Gulenists broke out at a time when supporters of CHP had almost completely lost hope of ever defeating or replacing the AKP government.

It is true that CHP and the Gulenists are not natural allies as they have fundamental ideological differences. However, they now have a common objective – to see Erdogan out of office – forcing them into closer alliance. In fact, there are growing speculations that both parties are now negotiating behind closed doors to form a coalition in order to make Erdogan taste his first electoral defeat in the March municipal elections. Will such an alliance deliver results? The power and reach of the Gulenist Movement is often exaggerated for various reasons by commentators on the left and the right.

Nobody really knows what percentage of the electorate is directly controlled by the self-exiled cleric: Is it one million, two million, or even larger? Perhaps it is smaller. But, for the moment, let’s suppose that Gulen commands several million votes. In reality this will not be enough to defeat AKP or tilt the elections in favour of CHP (in the 2011 elections AKP and CHP won 21.4 million and 11.2 million votes respectively). Thus, it is highly unlikely that, even in view of the crisis, AKP will garner less than about 40 percent of the votes in the local elections – delivering Erdogan mayorships in a majority of provinces in the country.

Neither Sharia, nor coup d'etat.

Istanbul and Ankara are two of the three largest provinces in Turkey currently ruled by AKP mayors. These cities are of great political, symbolic and personal importance to Erdogan. If in either city AKP performs worse than previous elections and loses the mayoral elections, this will further weaken Erdogan and seriously hurt his chances in the June presidential elections. Knowing this, the CHP-Gulenists coalition may focus their efforts exclusively on these two cities before the March elections. To that end, we may expect to see the on-going graft investigations, allegedly conducted by Gulenist prosecutors and police chiefs, to be further expanded into these two cities linking the incumbent mayors to the corruption scandal in the coming days and weeks.

Diversionary tactic

The current political crisis poses both opportunities and challenges to the CHP. There is now a slight chance that CHP candidates, with some help from the Gulenists, may defeat the incumbent AKP mayors in Istanbul and Ankara. However, the crisis poses a larger challenge than the opportunity it presents for the main opposition party. In order to divert public attention away from the graft investigation, Erdogan recently announced that he favours the retrial of hundreds of army officers and others who were convicted of a conspiracy to overthrow the government in the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer cases.

This is a calculated move by Erdogan and his party. They are trying to lead the public to believe that Gulenist agents are now targeting Erdogan’s government in the same way they treacherously plotted against their own national army with show trials built on fabricated evidence – a point of view shared by many in Turkey due to overwhelming inconsistencies, irregularities and flaws reported during the investigation and trial stages of the two cases.

In other words, the government hopes that the public will soon see the corruption charges from their perspective: If the evidence in Ergenekon and Sledgehammer cases were fabricated, then the evidence in the corruption case must have been fabricated, too – ie, millions of dollars found in shoeboxes must have been planted there by Gulenist agents. All in all, Erdogan’s “retrial” move was a very smart move. It not only diverts public attention away from the corruption investigation (at least for time being), but also tricks the main opposition party into a political trap.

CHP is not a party that is known for its democratic credentials. Rather, it is considered by most people as a dogmatic and staunchly militarist party which has often allied itself with anti-democratic forces and coup plotters. CHP, which throughout the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer cases argued the innocence of the defendants, has welcomed Erdogan’s recent remarks about retrials.

The retrial debate will continue to occupy the front pages of Turkish dailies in the weeks and months to come. The process will likely further reinforce CHP’s negative image in the eyes of many Turkish voters as the “party of coup-plotters”, and further diminish its chances of ever winning the government. As the Gezi protests, during which millions chanted: “Neither Sharia, nor coup d’etat”, made it clear, those who reject Erdogan’s religious authoritarianism will not settle for secular authoritarianism either. Unfortunately, neither Erdogan nor CHP leaders seem to have drawn any lessons from last year’s uprisings.

Yuksel Sezgin is Assistant Professor of Political Science, Maxwell School of Public Affairs, Syracuse University.

Follow him on Twitter: @yukselsezgin