The rich and the wretched of the Earth

Fictitious films can portray life’s harshest realities, writes scholar.

As it happened I watched Neill Blomkamp’s science fiction thriller “Elysium” (2013) just the day before I read the BBC report on the state of poverty in the United States.

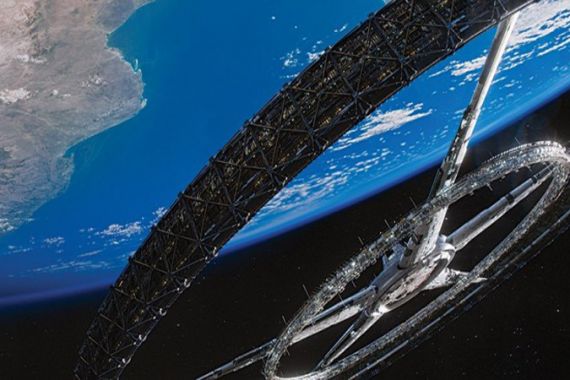

In “Elysium” – by the same director whose “District 9” (2009) had explored themes of racism and xenophobia with unnerving power and audacity – we are transformed to the year 2154, when the world is drastically divided between two classes of people: the rich and powerful who have gone heavenward and are living in a luxurious space station called “Elysium” and the poor who are suffering on a ravaged, overpopulated, dangerous, and degenerated earth. The wretched of the earth are mostly dark-skinned policed by ruthless robots, while the Elysian residents are mostly white (who prefer to speak French with an American accent to each other) floating in space in paradisiac comfort.

In the BBC report we read how “the income gap between the richest 1 percent of Americans and the other 99 percent widened to a record margin in 2012. The top 1 percent of US earners collected 19.3 percent of household income, breaking a record previously set in 1927. Income inequality in the US has been growing for almost three decades.”

In other reports we read even more staggering statistics:

Four out of 5 U.S. adults struggle with joblessness, near-poverty or reliance on welfare for at least parts of their lives, a sign of deteriorating economic security and an elusive American dream. Survey data from The Associated Press points to an increasingly globalized U.S. economy, the widening gap between rich and poor, and the loss of good-paying manufacturing jobs as reasons for the trend.

Between “Elysium” (which is supposed to be fiction) and the BBC and other reports (that are factual), one gets dizzy , as to which is which, for here fact and fiction come together to underline a ruthless reality that underlines the daily existence of humanity on a matrix that has defied its own measures of sanity and obscenity.

In The Wretched of the Earth/Les Damnes de la Terre (1961) Frantz Fanon examined in social and psychological details the dehumanising effects of the European colonialism on non-European nations – with the French in Algeria as the prototype of his analysis. In a critical passage, Fanon makes a stark distinction between the two sites of “the colonies” and “the capitalist countries” – as if these were two distinct entities:

In the colonies, it is the policeman and the soldier who are the official, instituted go-betweens, the spokesmen of the settler and his rule of oppression. In capitalist societies the educational system, whether lay or clerical, the structure of moral reflexes handed down from father to son, the exemplary honesty of workers who are given a medal after fifty years of good and loyal service, and the affection which springs from harmonious relations and good behavior–all these aesthetic expressions of respect for the established order serve to create around the exploited person an atmosphere of submission and of inhibition which lightens the task of policing considerably.

This distinction is definitive to Fanon’s reading of the capitalist-colonial division of the world:

In the capitalist countries a multitude of moral teachers, counselors and “bewilderers” separate the exploited from those in power. In the colonial countries, on the contrary, the policeman and the soldier, by their immediate presence and their frequent and direct action maintain contact with the native and advise him by means of rifle butts and napalm not to budge.

More than half a century after Fanon’s bifurcation between “the colonies” and “the capitalist countries,” as indeed at the time he was writing it, the binary looks quite fragile and conceptually dispensable. One quick glance at police brutality facing demonstrators anywhere from New York to Athens to Istanbul to Cairo to Tehran to Manama shows that bifurcation does not hold anymore. Police and security forces may attack demonstrators on horse in New York, on camel in Cairo or on motorcycle in Tehran – but the velvet gloves of oppression are off all over the world, and the scene of police brutality we witness in “Elysium” in Los Angeles (where the Rodney King beating took place on March 3, 1991) is now definitive in a global context.

The report of the state of poverty in the United States is a clear indication that relation of colonisation and exploitation between the rich and the wretched is not, nor has it ever been, limited between the classical bifurcation between the colonising in one nation, say France or UK, and the colonized in another, say in Algeria or India. We did not have to wait for the thing called “globalisation” to realise that colonialism has never been anything other than the abuse of labor by capital times geography.

Inequality depicted through film

The advantage of “Elysium” is that we see physically the bifurcation not between nations but between the earth and its wretched inhabitants and an extraterrestrial satellite full of rich people circumambulating around it on an orbit – so they can exploit it as viciously as possible without suffering the environmental or social consequences of that exploitation.

The moral of the story put together is not that the rich really live on another planet but that the depraved logic of capitalism is now, as it has always been, integral, organic, and definitive to the global condition of just being on earth. The state of poverty in the United States brings its poor people to the fold of humanity, as the rich of the world anywhere from Russia to China to Saudi Arabia to Europe or the US all look and live alike too.

The distance between the time Fanon wrote “Wretched of the Earth” and the time Neill Blomkamp’s made “Elysium” is covered by the extended logic of globalised capital in which all the false binaries between any fictive center of the capital and its peripheries have collapsed and by placing the 1 percent outside the earth roaming in space, Blomkamp has shown how in fact all such earthly bifurcations between “the West” and “the Rest” are entirely fictive and distorting reality.

The world is not divided between the colonising and the colonised nations, but between the rich and the wretched of all nations. The race, gender or geographical codification of the vicious logic of capitalism has camouflaged that simple and overriding logic. Without the delusion of colour, gender and national identity crudely camouflaging the cruel logic of capitalism, the wretched of the earth cannot be so easily divided by the rich so that they can rule them better.

The seminal battle in “Elysium” is fought between Max Da Costa (Matt Damon), making a meager living in Los Angeles and working at an assembly line for the Armadyne Corp., the company that has built Elysium, and the Elysian Secretary of Defense Jessica Delacourt (Jodie Foster) mediated by a band of earthly smugglers who finally manage to make all the wretched of the earth legal residents of Elysium.

If what takes Max Da Costa to Elysium is his defiant anger, the film that very much anticipates “Elysium,” Andrew Stanton’s “WALL-E” (2008) features a different course of attraction and defiance. In “WALL-E” we are actually witness to a romantic comedy, on a poor boy meets a rich girl theme, a love story between two robots – a rough and tumble color “boy” from the ravaged earth and a rich, fancy-pants, trigger-happy, white, blue-eyed “girl” from the heavens.

The two storylines are more or less the same. The earth has been brutalised and abandoned by mostly white people, and left to WALL-E (Waste Allocation Load Lifter – Earth-Class) to cleanup. The phantasmagoric love story between WALL-E and EVE (Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator) exudes the same emotional intelligence that informs Max Da Costa’s enduring love for his childhood sweetheart Frey Santiago/Alice Braga. Between the defiant anger of “Elysium” and the anthropomorphic machinations of “WALL-E”, the fate of humanity hangs in an injudiciously perilous balance.

Both on Elysium and Axiom, Max Da Costa and WALL-E, half-human, half-machine, lead a revolutionary uprising of “the undocumented aliens” and “rogue robots,” respectively, dismantling the astronomical distance between the rich and the wretched of the earth. May the force be with them!

Hamid Dabashi is Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York and the author of Brown Skin White Masks (2011).