Who is the terrorist? Violence and power in Egypt after Morsi

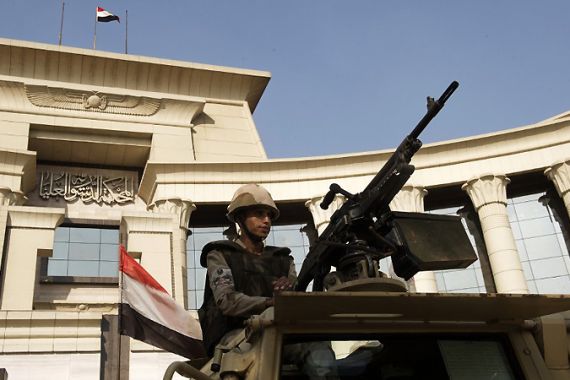

Despite the July coup, the military’s position is not as strong as it seems given Egypt’s weak economy.

“… I saw that in Paris the simple and uninstructed multitude had actually been led by the enemies of the people into a cordial contempt for the Republic… I said to myself: the Republic is lost, barring some stroke of genius that could save it; surely monarchism will not hesitate to regain its hold upon us… I saw no one who might be disposed to revive the courageous mood of earlier days. And yet, I told myself, the same ferment of zeal and of love for all men still exists.”

So declared Francois-Noel Babeuf, the great political agitator and journalist of the French Revolutionary period and seminal advocate of communism. Babeuf uttered these words while on trial for attempting to overthrow the Directory, the current Republican government, in order to convey the situation revolutionaries faced eight years into what can be described as a still-unfinished revolution. Eloquent though his words were, Babeuf was still found guilty and guillotined in May 1797.

Despite Babeuf’s fate, these words should comfort revolutionaries in Egypt gripped by an increasing sense of futility in the weeks since the military’s removal of Mohamed Morsi. Most revolutions go through moments as low as, and even far lower than Egypt’s present situation. And in few have the social, political and economic dynamics for a return to a revolutionary consensus remained as favourable as they are here.

But more interesting than Babeuf’s inspiring example and what they might augur for Egypt are his views on violence. His vision for France was among the most progressive and egalitarian of his era, but Babeuf was no pacifist. Indeed, like most participants in the French Revolution’s various sides and factions, he saw the use of large-scale, mass violence as a normal, necessary and strategically sound practice. Behind The Terror were many ordinary revolutionaries who felt the violence – and equally important, fear – that defined it were not just an acceptable price to pay but a crucial tool to ensure the survival of the revolution and prevent the far greater level of violence which, they argued, would be unleashed should the counter-revolution succeed.

Terror’s many truths

I can’t help thinking of Babeuf’s words, and his views on terrorism, as I try to decipher the competing accusations by the Egyptian military, government and media, and the Muslim Brotherhood and its supporters, that the other side has engaged in unlawful violence and even terrorism against the Egyptian people. While the United States and other governments have often tried to limit the legal definition of terrorism to acts committed by non-state actors (except for “rogue states”), the weight of international law still considers terrorism to be deliberate attacks on civilians by either governments and/or non-state groups.

|

|

| Latest developments on Egypt crisis |

In Egypt today, the evidence of deliberate murder and terrorism both by government forces and members of the Brotherhood and (allegedly) radical religious forces is too overwhelming to dispute. Yet at the same, states have a greater responsibility to uphold the rule of law and international human rights standards even – indeed, especially – when citizens are not. And in this regard, as the Guardian‘s Patrick Kingsley damningly argues, “Amid all the rhetoric about Islamic terrorism, few seem to realise that most of the terrorising has in fact come from the state”.

If ever there was a situation that screamed for the creation of a UN-mandated truth commission, it is the violence of the last two months in Egypt. Yet counting bodies and figuring out which side has behaved more terroristically are ultimately not the most important tasks facing those seeking to ameliorate the present violence. Rather, it’s understanding why various contending forces have resorted to such violence, even though it is so clearly counter-productive to their long-term legitimacy and even survival.

Colonising yourself, over and over

The military, its clients and allies, and the Brotherhood have all attempted to define themselves as the protectors, guarantors and even vanguards of the January 25 revolution. Such claims have long been used to justify all manner of violence by states and the forces opposed to them. If they seem ludicrous in the face of the events of the last two months, it would be no more accurate to assume they represent competing elements of a counter-revolutionary bloc.

Rather than merely counter the revolutionary impulse that swept over Egypt in early 2011 post-January 25 whether led by the SCAF or the Brotherhood have centred around how to manage a passive revolution that could absorb the incredible energy – or “strength”, as the Italian political philosopher Antonio Negri has termed it – of the masses of Egyptians, providing just enough change and development to diffuse or deflect the revolutionary impetus and hopes of the broader population, while marginalising and ultimately excluding the remaining revolutionary voices from a meaningful share of power.

For a time, the Brotherhood, with its hierarchical, patriarchal, authoritarian yet techno-modern worldview and (ostensibly) deep social roots, seemed like the perfect group to manage the passive revolution without threatening the power and privileges of the Mubarak-era elites. It’s hard to say if it was resistance by old-regime elements within the state, or arrogance, incompetence and/or greed on the part of the Brotherhood, or some combination of all of these factors, that was most responsible for the singular failure of the Brotherhood to manage the transition period.

But by the spring of this year, a new revolutionary wave was gathering energy, one based on the same raw power – Tamarrod, Rebel! – as motivated the original revolutionary explosion of January 2011 (Leave!/Irhal!) or Tunisia just before it (Degage!); yet one more easily redirected and coopted than its original incarnation.

|

|

| Egypt court orders Mubarak released |

This dynamic raises the question of why the revolutionary forces whose actions precipitated these power struggles were largely excluded from them, and so unable meaningfully to shape the post-Mubarak political system until Tamarrod burst onto the scene this spring. The answer owes to the fact that the terrain of battle in post-Mubarak Egypt – control over the institutions and ideologies of the Egyptian state – is one where revolutionary forces are at an extreme disadvantage once the initial burst of revolutionary energy is spent.

It is not Egypt’s state that is the problem; the very institution and discourses of the modern nation-state are inextricably tied to a matrix of discourses – capitalism, the still-living impact of centuries of imperialism and colonialism, nationalism and the creatively destructive impulse of modernity at large – that have most often produced states that are in form and function as much criminal enterprises and vehicles (or at least conduits) for terror as they have institutions of governance. In particular, the kind of militarised nationalist ideology that is suddenly dominating Egypt has always justified, deflected and even championed the skewed balance of power and the violence at the heart of most societies.

In the colonial era, through which most every Arab country passed, the most negative effects of this dynamic were displaced onto the colonies; inside the colonised territories it was displaced locally according to existing and imposed social, economic and political hierarchies. As Michel Foucault described it in his 1976 lectures at the College de France, the models and techniques of rule that emerged and were so brutally deployed in the colonies by Europe “boomeranged” back on the mechanisms, apparatuses, institutions and techniques of power in Europe, allowing European states to “practice something resembling colonisation, or an internal colonialism, on [themselves]”.

As for the countries they colonised, the boomerang has hit harder each time it has ricocheted back to the region, from the still dependent immediately postcolonial governments, through the decades of “revolutionary” military rule into the neoliberal era that began in the 1970s, and incorporated key segments of the countries’ elites by the 1990s. Whether under “liberal”, “socialist” or “Islamist” states, membership in the nation has long been bounded and sealed by a near-permanent “state of exception” or removal from the body politic, into which any citizen could be placed at any time, and which overlay the ethnic and sectarian webs that always lurked beneath official nation-centric identities.

The threat and reality of social as well as physical death has always been at the heart of how power in its various modalities – pastoral, sovereign and disciplinary, as Foucault categorised them – has functioned in the Arab world, where patriarchal familial and patrimonial political structures are still the rule. In the West these forms emerged one after the other, albeit with significant overlap; in the Arab world they were from the start and remain today tightly enmeshed, each one reinforcing the others’ ability to shape the contours of peoples’ identities and actions in ways that make progressive systematic change difficult both to imagine and pursue.

Given the synergistic power of modern capitalism, colonialism and nationalism, it’s easy to understand how limited is the opportunity for a revolutionary movement to bring about a major change in the structure of governance in a country. If it doesn’t succeed quickly in a direct assault on the state that overturns the existing political structures, and rerouts the myriad power conduits that pass through it, the chances of transforming the state from within are fairly slim. (And as the experience of Iraq and now Libya remind us, dismantling a state is a lot easier than building a new one up, no matter how many resources are at one’s disposal.) Thus most revolutions become passive soon after what appears to be the height of their power.

Changing balance of power?

The rapid spread of education and the technological revolution of the last generation did open new spaces for younger Arabs to develop new forms of resistance against authoritarian states. When economic conditions became dire enough, the tools at the disposal of a new generation of activists enabled the rise of the first great revolutionary tide of the twenty-first century.

|

Today, it seems as if Egypt has returned to the Mubarak era. |

The “revolutionary youth” who led the 18-day Tahrir-centred revolution of January-February 2011 had the tools, discourse and lack of fear to shake and even partially dislodge the system. But they did not have the ability to create a new state structure in its place, one based on very different modalities of power not dominated by the existing power elites. Neither could Egypt’s much-maligned liberals, who like liberals the world over are constitutionally incapable of pressing for revolutionary socio-economic and political change, precisely because their interests lie closer to the existing elites than to the mass of bitterly poor, “illiterate” (as ElBaradei and other liberal leaders derisively termed them) and conservative compatriots who would be the major beneficiaries of any revolution for “bread, freedom, social justice and dignity” worthy of the name.

Today it seems as if Egypt has returned to the Mubarak era, with repression, propaganda and state-sponsored violence at even higher levels than before January 25, 2011. But while things look desperate from the perspective of those pushing for revolutionary change, in fact the military’s position is not nearly as strong as those spreading “Mubarak 2014” memes on Facebook (whether sarcastically or earnestly, it’s still too early to tell) might assume.

Via any mechanism possible – aid, fiscal stimulus, increased production and commerce – Egypt needs tens of billions of dollars added to its GDP now. Not in five or ten years, but now, if it is to address its crippling social, economic, and infrastructural problems. Even with massive Saudi and Emirati aid, the existing state and power system is simply too corrupt to channel wealth and development to the majority of Egyptians, regardless of how much foreign aid and investment pours into the country.

Only the wholesale transformation of the country’s political economy, which no one but the revolutionaries has any interest in bringing about, can achieve that. Egyptians have already known this, which is why the January 25 Revolution demanded not merely Mubarak’s replacement, but the downfall of the military government and the entire system.

Unless the military can pull off an unprecedented economic miracle in the coming months, it should surprise no one if these chants are heard in Tahrir once again, and this time the military and the deep state will not have the Brotherhood to blame.

Mark LeVine is professor of Middle Eastern history at UC Irvine and distinguished visiting professor at the Centre for Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University in Sweden and the author of the forthcoming book about the revolutions in the Arab world, The Five Year Old Who Toppled a Pharaoh. His book, Heavy Metal Islam, which focused on ‘rock and resistance and the struggle for soul’ in the evolving music scene of the Middle East and North Africa, was published in 2008.

Follow him on Twitter: @culturejamming