The 9/11 trial begins: Why second-class justice harms everyone

The trial of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four others should have been prosecuted in a federal court.

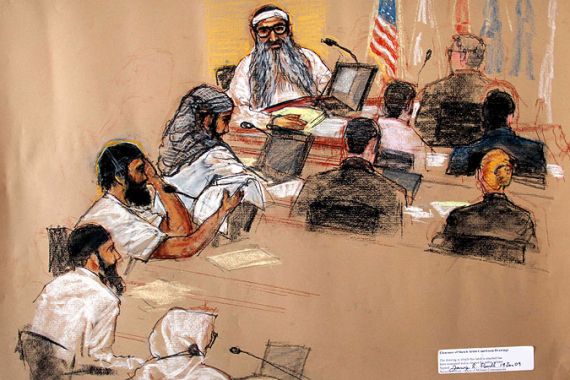

New York, NY – Proceedings are finally underway in the case of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) and four co-conspirators, who stand trial before a military commission at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, for their role in the 9/11 terrorist attacks. While it is too early to make any definitive judgments, the trial highlights the continuing – and inevitable – flaws of military commissions.

The trial is already off to a rocky start. Saturday’s arraignment – normally a brief proceeding – lasted 13 hours, as the defendants engaged in various tactics aimed at undermining the trial’s validity. Defendants refused to listen or talk to the judge, removed their headphones (which carried the Arabic translation of the proceedings), and delayed the hearing by praying. One defendant shouted to the judge that guards at the prison might kill him.

| Defence lawyer criticises Guantanamo trial |

The trial judge, Colonel James L Pohl, failed to establish control over an increasingly chaotic situation. The failures, however, go beyond any shortcomings on the part of Judge Pohl, who, if anything, was too patient with the defendants. They underscore the perils of trying such a high-stakes case in a tribunal whose raison d’etre was to evade the rule of law and deny justice.

How, one might ask, would the arraignment have gone had the administration not bowed to political pressure and prosecuted the case in federal court, as originally planned? Almost certainly, much better. The defendants might still have tried to delay and disrupt the proceedings. But a federal judge not only would have had tools at the ready to cut through these tactics; a federal judge also would have had the confidence to do so without worrying about anyone attacking his or her impartiality or the legitimacy of the proceedings.

The arraignment thus highlights a problem that has plagued military commissions since President Obama sought to resurrect them three years ago: No matter how much their procedures are tweaked, the commissions still lack the competence and institutional experience of federal courts.

That the defendants were imprisoned and reportedly tortured in secret CIA “black sites” for years before being transferred to Guantanamo undoubtedly raises complex and challenging legal issues. How, for example, should a judge handle the fact that one of the defendants, KSM, was waterboarded 183 times? These complexities, however, provide another reason to try the cases in a venue with established rules and procedures rather than in a jerry-rigged military commission.

Saturday’s arraignment exposed an additional fallacy of military commissions: that they would prevent the defendants from turning the trial into a PR event. In fact, the commission appears to have made it easier for the defendants to put the government on trial and shift the focus away from where it should be: on the heinous alleged acts of the defendants themselves.

Torture, meanwhile, continues to haunt the proceedings. When one defence counsel tried to explain that his client’s longstanding abuse was the reason he refused to enter the courtroom voluntarily and so was brought shackled to a chair, the audio feed to press and NGO observers was cut. While this particular discussion was later released as part of the public transcript, the commissions make it easier to censor descriptions of past mistreatment to shield government misconduct and avoid embarrassment.

Defence attorneys, moreover, continue to face significant restrictions on their ability to represent their clients. The defence department, for example, has sought to prohibit attorneys from discussing information contained in documents such as an International Committee of the Red Cross report on detainee abuse that the rest of the world has seen and that may bear on key aspects of the trial, particularly the determination of whether the defendants should receive the death penalty.

Perhaps the most revealing – and disturbing – moment on Saturday came when one defence attorney asked the court: “Do you believe or accept that the rights under the United States Constitution, the individual rights, apply in these proceedings?” To which Judge Pohl replied: “I think it’s an open question, and … I’m subject to be persuaded either way with the assistance of counsel’s briefs.”

Or, to put it more bluntly, the trial judge himself does know whether the most basic constitutional rules apply in the case before him.

The families of victims understandably expressed anger and frustration at the defendants’ behaviour. But the defendants’ attempts to attack the legitimacy of the proceedings should come as no surprise. Nor should their attempts to expose the details of their brutal treatment by US officials – treatment that could and should have been the subject of its own war crimes prosecution.

By choosing to prosecute the 9/11 defendants in a military commission, the United States has denied the families the untainted justice that they would have received had the case been prosecuted in federal court. The defendants, to be sure, might have questioned a federal court’s credibility and competence, but no one else would have. Yes, there would have been difficult legal questions, but those questions would not have concerned the basic legitimacy of the forum.

Trying the defendants in a military commission has ensured a legacy of controversy that will tarnish the families’ quest for justice, regardless of what happens to the individual defendants in the case.

The United States, in short, has placed perhaps the most important terrorism trial in its history in a second-class court with untested procedures. What is most striking – and what will continue to haunt the United States – is that there was no good reason for this choice. Fearmongering and political gamesmanship are what prevented this case from being prosecuted where it should have been: in a federal court.

Jonathan Hafetz is Associate Professor of Law at Seton Hall University School of Law and the author, most recently, of Habeas Corpus after 9/11: Confronting America’s New Global Detention System.