Of pride, nationalism, loyalty and deceit

American cluelessness of Pakistani attitudes toward the jailed Dr Shakil Afridi is what is so disturbing in this affair.

Washington, DC – Once again, voices of righteous indignation are being raised dramatically in Washington. Senators Carl Levin and John McCain, the two ranking members of the Senate Armed Services Committee, are perhaps the most strident among them, having just pronounced the actions of a Pakistani court to be “shocking and outrageous”. Should the government of Pakistan fail to undo this judicial travesty, they assert, it “will only do further harm to US-Pakistani relations, including diminishing Congress’ willingness to provide financial assistance to Pakistan”.

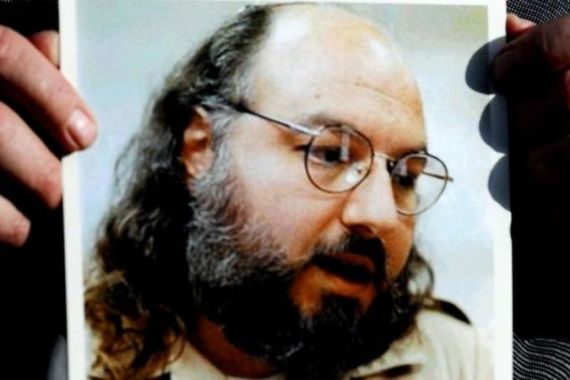

The list of serious irritants to US-Pakistani relations is long these days. But the cause of this most recent spate of bluster and threats was the sentencing last Wednesday by a Pakistani tribal court of one Dr Shakil Afridi, a Pakistani public-health physician convicted of having provided intelligence assistance in support of US efforts to track down Osama bin Laden. Dr Afridi is alleged to have organised an ostensible vaccination campaign in the vicinity of bin Laden’s suspected hideout in hopes of inoculating one or more of the resident children, thereby potentially gaining a DNA confirmation of the al-Qaeda leader’s presence. What other assistance the Pakistani physician may have provided, if any, we do not know. No one suggests Afridi was aware of the actual target of the Americans’ interest. Precisely what he thought he was doing, or his motives in doing it likewise remain uncertain. What is clear, however, is that Pakistan considers him a traitor, and that he has been sentenced to 33 years in prison.

| Pakistani doctor jailed for helping CIA find bin Laden |

Just as they did shortly after Afridi’s arrest in the aftermath of last year’s raid on bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound, however, various US officials are expressing a combination of outrage and incomprehension. Secretary of State Clinton has just described Afridi’s treatment as “unjust and unwarranted”. Speaking from Air Force One, the White House spokesman has underscored that Afridi was providing “…assistance not against Pakistan, but against al-Qaeda…” And in an action designed more to inflict insult than injury, the Senate Appropriations Committee has voted unanimously to cut aid to Pakistan by $33 million – one for each year of Dr Afridi’s sentence.

There appear to be several motives behind these actions. Some US officials appear stung by the appearance of America’s having abandoned Afridi to his fate, and are concerned at the disincentive this could provide to others. But underlying such practical considerations is a far more profound moral indignation at the notion that Pakistan would want to punish someone for doing what to American eyes is clearly the right thing. From the American optic, if Pakistani officials are outraged that one of their own would attempt to aid America against al-Qaeda, isn’t this yet more proof that Pakistan is aligned with the enemy?

The merits of the case aside, American cluelessness regarding Pakistani attitudes and the reasons for them is what is most disturbing in this entire affair. From the Pakistani viewpoint, the United States’ obvious lack of trust in having declined to solicit their assistance in verifying bin Laden’s presence in Abbottabad or in trying to effect his capture is a national insult. And in having launched a secret commando raid on Pakistani territory, in an Army town no less, the Americans have deftly turned insult into national humiliation. To a Pakistani, the notion that one of their nationals would have been complicit in these perceived outrages against their sovereignty is simply unforgiveable, no matter that his assistance was marginal at best – he apparently never did acquire the hoped-for DNA – and that he could certainly not have anticipated the nature of American actions to come.

Make no mistake, as this observer has asserted previously, the Americans had virtually no choice in acting unilaterally in Abbottabad. The state of distrust between the two countries and their intelligence services at the time, as well as the possibility of some level of official Pakistani complicity in bin Laden’s safe keeping would have made it impossible for the Americans to bring Pakistan into their confidence. The great tragedy in this episode is that, given the importance attached to bin Laden, the US could not have acted other than as it did, regardless of the consequences. What is incomprehensible to me, however, is the apparent American expectation that Pakistanis would see the situation in the same way.

| Inside Story Americas: Breaking point for US-Pakistani relations |

The case of Jonathan Pollard, a civilian employee of the US Department of Defence who provided Israeli intelligence with thousands of classified documents, may be different from the Afridi case in important respects. But as Israelis have pointed out, his espionage was purportedly aimed at helping an ally, not an enemy. And many in Israel would have considered the information Pollard acquired surreptitiously something which the US ought by rights to have provided them voluntarily. Indeed, Pollard is considered a hero in Israel, and successive Israeli governments have made high-profile attempts to win his release from prison.

But an American nationalist, such as this writer, is bound to see the situation in distinctly different terms. To me, Pollard is a traitor to his country who has violated the public trust, and is fully deserving of his punishment. The more Israeli officials have lobbied publicly on his behalf, the more those who think as I do have dug in their heels.

It should not be a surprise that Pakistani nationalists would feel similarly. It is a truism that the lines which divide political entities and cultures likewise divide the minds of men. Given their own nationalistic tendencies, it should not be so difficult for American officials now making over-heated public statements on Afridi’s behalf to understand that in doing so they are not doing the good doctor any favours. One might hope that given time and quiet – repeat, quiet – diplomacy, it might be possible to relieve a bit player on the margins of grand historical events from the consequences of his being caught up as an unfortunate political symbol, but if US officials believe they will accomplish this through a combination of public brow-beating and financial blackmail, they should think again. And while they are at it, they might consider the fact that this is a strategic relationship with little margin for further gratuitous stress.

Robert Grenier is a retired, 27-year veteran of the CIA’s Clandestine Service. He was Director of the CIA’s Counter-Terrorism Center from 2004 to 2006.