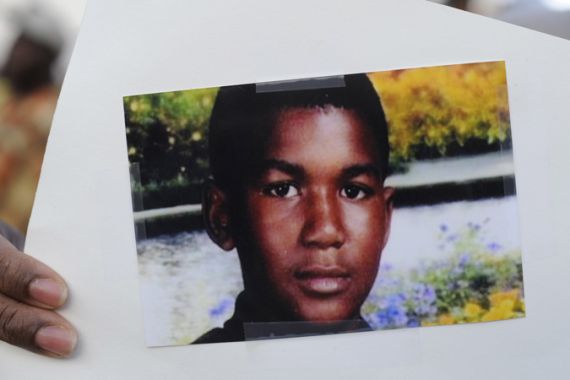

Trayvon Martin, a victim in the NRA’s culture war

When Florida passed the US’ first ‘Kill at Will’ law in 2005, it was a solution in search of a problem.

“There was not a single instance in Florida of a single person suffering in any way. This was a solution in search of a problem.” – Florida legislator Dan Gelber on Florida’s “Kill at Will” law. The Ed Show, March 22.

San Pedro, California – When Florida passed the nation’s first “Kill at Will” law in 2005, it was a solution in search of a problem, which multiple prosecutors warned against – much like the more recent flood of voter fraud laws that threaten to prevent millions of qualified voters from casting their votes this coming November. As other states, such as Pennsylvania, have adopted similar laws, the same objection has recurred repeatedly – where’s the evidence of harm under existing law?

But the lack of demonstrable existing harm wasn’t the only thing “Kill at Will” laws and “voter fraud” laws had in common. Both served to shift power in favor of traditionally entitled groups, both were promoted using a sanitised language of responsibility and protecting the lawful order, and both were spread across a network of states via a relatively obscure, but powerful right-wing lobbying organisation, ALEC – the American Legislative Exchange Council, which wrote “model legislation” for typically understaffed, part-time legislators, who didn’t seem to have time to investigate to see if there was any actual problem that needed fixing. (Not accidentally, de-professionalising the US Congress to make it more like state legislatures is one of the perennial goals of the GOP, resurfacing each time they win a fresh new majority.) Al Jazeera contributor Cliff Schecter illuminated some of ALEC’s more sinister, racially-oriented doings here, earlier this week.

| Obama calls Florida teen killing ‘tragedy’ |

But none of these facts were what alarmed police and prosecutors who organised unsuccessfully against Florida’s “Kill at Will” law. They were alarmed by the welter of problems it would create – especially a clearly foreseeable rise in reckless “justifiable homicides”, which quickly came to pass, as later reported in a five-year review of the law in the Tampa Bay Times, which I cited in my earlier column, “Who Killed Trayvon Martin?“

While it would be a mistake to simply assume that Trayvon Martin’s murder is directly justified or protected by Florida’s “Kill at Will” law, as I’ll explain below, the law has clearly sown confusion and disorder that has allowed dozens of murderers to go free – the exact opposite of the enhanced public safety that right-wing “law and order” rhetoric pretends to offer. Although the details may still be a bit murky or disputed, the broad outlines of how this came about are relatively clear.

Right to protect

Like all jurisdictions under Anglo-American law, Florida’s law on the use of force distinguished significantly between conduct in public and private defence of one’s home and property. In the public sphere, the use of force was strongly discouraged: it could only be used in self-defence or defence of others under criminal attack, and only then subject to additional conditions. There is generally a duty to retreat, if one can do so safely, rather than engage in violent confrontation. Private citizens are not supposed to act as judge, jury and executioner. Whatever short-term gains there may be, they are overshadowed by the long-term consequences of a decidedly more violent culture tending towards the Hobbesian “state of nature” – a “nasty, brutish and short” life lived in an unending “war of all against all”.

This contrasts sharply with the private sphere of one’s own home (and by extension other private property), where the “castle doctrine” applies, granting special protections and immunities, including the qualified right to attack – even kill – an intruder without being liable for prosecution. (Qualifications vary by statute in different jurisdictions and over time.)

In 2005, under pressure from the NRA, whose Florida lobbyist Marion Hammer was a former national NRA president, Florida passed a law that not only dramatically strengthened the state’s castle doctrine – providing an absolute right to kill an intruder – but that also broke radically with with long-standing traditions of Anglo-American law in three different ways. (Compare the 2004 law with the 2005 law.) First, it substantially reduced the distinction between the private and public spheres, largely (though not entirely) equating one’s own home with any public place one has a legal right to be. Second, it explicitly eliminated the duty to retreat. Third, it elevated and transformed justifiable homicide from a legal defence available at trial to an absolute right to be immune from investigation, much less criminal prosecution or civil suit. As I described in my previous column, Florida law now states:

“A person who uses force as permitted in s. 776.012, s. 776.013, or s. 776.031 is justified in using such force and is immune from criminal prosecution and civil action for the use of such force…. A law enforcement agency… may not arrest the person for using force unless it determines that there is probable cause that the force that was used was unlawful.” [emphasis added.]

Any one of these three changes would by itself constitute a radical break with existing legal precedent. In combination, they created a profoundly disorienting change in the law that still has judges, prosecutors and police befuddled and confused – as has been amply reflected in the coverage of Trayvon Martin’s murder. After the law was passed, Florida newspapers reported substantial chaos and confusion over the meaning of the law, with wildly varying interpretations by police, prosecutors and judges, which has apparently only subsided into a variety of questionable interpretations, as exhibited in the case of Trayvon Martin’s murder.

Changing laws

The confusion is hardly limited to Florida. In Texas, where a less extreme version of these changes were implemented in 2007, the first controversial case – which emerged within months of the law going into effect – involved one Joe Horn, who shot two would-be burglars in the back as they escaped from a neighbour’s house. “The laws have been changed in this country since September the first, and you know it,” Horn told the 911 operator, who tried unsuccessfully to keep him indoors until the police arrived. “I’m going to kill them.” And that’s exactly what he did – just as the police arrived. (He later dishonestly claimed, “I just went outside to get information for the police”.) Texas law actually hadn’t changed to make Horn’s actions legal. Using lethal force to defend a neighbour’s house wasn’t legalised, nor was killing criminals who were fleeing. But Horn accurately guessed that none of that really mattered. A grand jury later refused to charge him. Horn was white. The men he killed were both people of colour, and one was an illegal immigrant. What the new law actually said didn’t matter. Not in the real world. And certainly not in Texas.

Yet, in the right circumstances – with the whole nation watching – what the law actually says can become relevant. When it does, as American University law professor Darren Hutchinson has painstakingly explained (“Trayvon Martin: ‘Stand Your Ground’ Rule Has NOTHING To Do With This Case”), enough elements of traditional law remain in place to both justify an arrest and sustain a conviction in Trayvon Martin’s murder, as well as, presumably, many other cases as well. In particular, the “reasonable person” standard does not allow prejudice-driven fantasies or other psychological defects to justify use of force, much less murder. Additionally, the “probable cause” standard “that the force that was used was unlawful” is much easier to meet than seems to be widely assumed.

|

“Those whose privileges have been eroded want the old order back, and vigilantism is one way to get it.” |

Hutchinson’s point was echoed by political science professor Scott Lemieux at the American Prospect. Following in a more succinct summary of facts in the case under the standard of a “reasonable” threat, Lemieux reached a similar conclusion about the law itself, noting:

“If Zimmerman gets away with killing Martin, it’s not just the statute that bears responsibility. It’s how Florida’s policemen, prosecutors, judges, and juries have constructed its ambiguous language. Many actors will have shared in creating the injustice should the killer of Trayvon Martin go unpunished.”

And that’s really what this case is all about – and what the NRA and ALEC’s rewriting of gun laws is all about as well. On one side, there is the long-standing common law requirement of acting in a reasonable manner, and standing in judgment before one’s peers. On the other side – by reshaping the letter, the spirit, and the interpretation of the law – lies vigilante “justice” – the individual or mob as judge, jury and executioner, all in one and all at once. Whatever they think, want, feel or do in the moment is by definition “reasonable”. Questioning them in the slightest is not. It could get you killed.

As previous privileges drain away over time, and the letter of the law actually comes to protect those who formerly had few, if any, rights that were actually protected, those whose privileges have been eroded want the old order back, and vigilantism is one way to get it.

Paul Rosenberg is the senior editor of Random Lengths News, a bi-weekly alternative community newspaper.

Follow him on Twitter: @PaulHRosenberg