Lessons from the 1970s

During the most significant popular mobilisation since the 1970s, the past must serve as an example.

London, UK – General accounts of radicalism tend to concentrate on the 1960s. They also place a particular emphasis on those elements that later proved useful to marketers. We constantly hear about the students’ revolt against the staid morals of earlier generations – the music and film industries have retold that story ever since. But we hear less about the joint efforts of American students and civil rights campaigners to create an alternative to the Republican-Democrat duarchy. Apple was happy to use clips of Martin Luther King in its adverts, but the mainstream has little time for his opposition to the war in Vietnam and his demands for economic and racial justice.

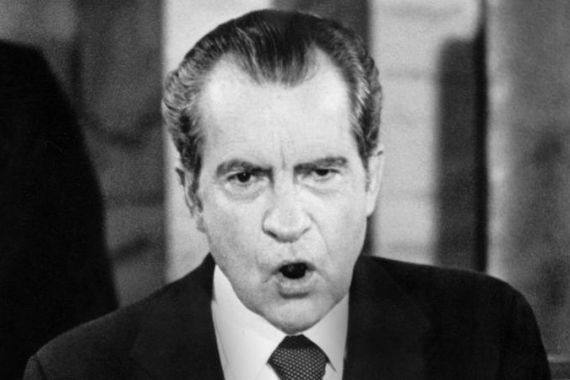

The high watermark for popular engagement in politics comes some time later, in that unloved decade, the 1970s. In Britain a series of strikes against Ted Heath’s inept administration eventually forced an election in 1974, which the government lost. In the same year Nixon resigned the presidency as the Watergate scandal metastasised. In 1976, the bicentenary of the Declaration of Independence, the Americans elected a President promising change and democratic renewal. The popular movements that first emerged in the 1960s seemed on the brink of transforming both America and Britain.

That’s certainly how it seemed to those who ran politics and the economy. Scandinavian social democracy haunted the waking nightmares of American businessmen. One of them worried that “if we don’t take action now we will see our own demise”. Another complained in a revealing metaphor that “we are like the head of a household, and the public sector is like our wife and child. They can only consume what we produce”.

Democracy crisis

The Trilateral Commission is an obscure talking shop whose current members include the (unelected) Prime Ministers of Italy and Greece. In 1975 it was sufficiently worried to put together a book entitled The Crisis of Democracy.

One of its authors, Samuel Huntington, identified the core of this crisis, from the perspective of the governing elite. In the 1960s and 1970s, “previously passive or unorganised groups in the population… embarked on concerted efforts to establish their claims to opportunities, positions, rewards and privileges, which they had not considered themselves entitled to before”. Blacks, women, and “clerical, technical and professional employees in public and private bureaucracies” – that is, the vast majority of the population – were seeking the kinds of power that the wealthy and their trusted servants considered theirs by right. Crucially, they were seeking control of the state through the electoral process.

Democracy could only work, explained Huntington, if there was “some measure of apathy and non-involvement on the part of some individuals and groups”. The so-called crisis of democracy would only end when the majority gave up their ambitions to secure an effectual say in politics and hence economics. It was time for the powerful to assert “the claims of expertise, experience and special talents” over and above the claims of democracy.

In the years that followed businessmen in Britain and the United States spent huge sums on a campaign to establish new forms of expertise and to persuade the public that their chosen favourites had special talents. Neoliberal economists who had been dismissed as cranks suddenly became the prophets of true freedom and national renewal. Meanwhile, strenuous efforts were made to break up popular coalitions by exploiting and highlighting existing social tensions. Men were set against women, whites against blacks, blue collar patriots against egghead liberal intellectuals and so on.

At the moment, our rulers can only do so much to persuade us that they have special talents and expertise. The financial crisis has made a mockery of their claims to basic competence. This goes largely unmentioned in the media over which they continue to exercise control. But free markets and deregulation no longer seem like a royal road to general prosperity.

But the established powers are having much more luck in setting potential allies against one another. The fault lines in society, the points at which sentiment and identity can be exploited, are different this time. But the game remains the same. So, in the US, mainstream politics organises itself around the disputes over lifestyle and values. The secular are menaced with the bogey of fundamentalism, the God-fearing with death boards and compulsory abortion. Such things make a wonderful alternative to a politics of redistribution and retribution.

‘Scapegoats’

In Britain, politicians and opinion-formers are working hard to shift attention onto what Philip Lesly once called “that traditional source of scapegoats, the isolated and oppressed”. There is a particular focus on welfare “scroungers”. The money lost through benefit fraud seems to obsess newspaper editors who remain insouciant about much greater cost of tax avoidance and evasion. It is odd, in a way, because exotic tax arrangements would be much easier for them to investigate. There is also a great deal of talk about the generational conflict. The young are being set against the old.

The Romans, who knew a thing or two about force and fraud, called this sort of thing “divide and rule”. But while they spend some of their time trying to make us hate one another, our rulers also try to unify us in ways that suit them. This year in Britain will see both the monarchy and the Olympics being used to create a sense that our current arrangements are both inevitable and just. Meanwhile, in the US, the prospect of war reminds the population that they live in a dangerous world and must trust their leaders. Now that economics stands revealed as a sham, war is the established order’s last mystique.

By the end of the seventies, popular movements for a greater say in government had been successfully turned into a campaign to “get government off our backs”. Reinvigorated right-wing parties called for liberation from stifling regulation and meddling bureaucrats. They promised a restoration of national self-confidence after years of drift and confusion.

It is important to grasp the parallels with our own era. Though the major media and the rest of the ruling apparatus insist in public that everything is fine, many of them know full well that events could easily slip from their grasp. From their perspective, student protests, occupations and assemblies, and the growing energy and independence of working people, are serious problems.

A generation ago, previously excluded groups were making common cause and trespassing on the prerogatives of the powerful. Our rulers were desperately worried that the majority would assert effective control of the state, and hence of the economy. They took action to head off the danger and they succeeded.

The forces ranged against the menace of democracy remain alert and disillusioned. Meanwhile, we are still easily distracted and deceived, still prone to hatreds and resentments that do us no good and that keep us at a distance from one another. Our prejudices make us easy meat for the skilled mechanic of sentiment.

But, still, we must manage to piece together a programme for economic renewal through increased popular participation in government, and discover a strategy for implementing this programme, without unnecessary fuss. We came far closer last time than anyone now cares to recall. But perhaps we were failed because we did not fully appreciate the threat that democracy poses to rule by a rich and well-connected few.

We do not need to sweep away the ruling class we have. On the contrary, we need to enlarge it, until it includes everyone.

Dan Hind is a journalist and publisher. He is the author of The Threat to Reason and The Return of the Public. Common Sense: Occupation, Assembly, and the Future of Liberty is published online on March 20.

Follow him on Twitter: @danhind