Europe’s failure to integrate Muslims

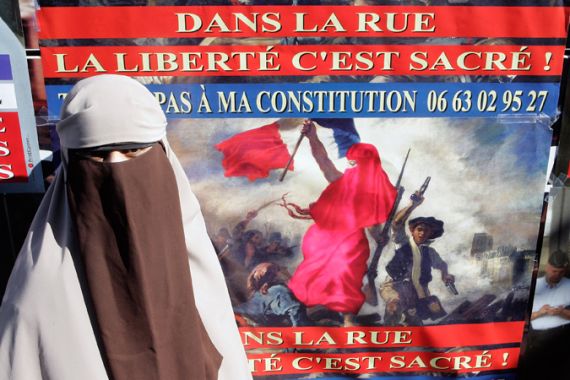

Laws restricting Islamic symbols in the public sphere are fuelling political distrust and a shared sense of injustice.

Boston, MA – Eight years have passed since France’s Assemblee Nationale launched the opening volley of a decade-long effort to reduce Islam’s visibility within migrant-origin communities across Europe. In the last few months alone, an anti-burqa law was passed in the Netherlands, a new headscarf bill and restrictions on halal slaughter are under consideration in France, and a German Supreme Court ruling banned Muslim prayer in public schools.

As Muslims and non-Muslims despair about the prospect of long-term Islamic integration in 21st century Europe, disagreement over the urgency and necessity to restrict Islamic symbols in the public sphere – from clothing to architecture and food – is at the origin of a potentially grave misunderstanding.

Religion is not the primary factor of identity for most European Muslims, but the current atmosphere has enhanced a feeling of group stigmatisation and a shared sense of injustice where previously few bonds existed. This has fed a growing confrontation, foreshadowed in two competing narratives of victimisation dividing Muslims from non-Muslims in Europe, which continue to gain strength.

In the first narrative, “native” European populations are told by political parties that many mainstream Muslim religious practices – from headscarves to halal meat – are in fact insidious attempts to impose Islamic rules on non-Muslims and they must be halted. As the Norwegian right-wing terrorist manifesto unoriginally put it, the year is 1683 and the Gates of Vienna are under siege.

Against this narrative is the view, held by many Muslim community leaders, that European governments are uniformly repressive and intolerant of diversity. In that account, it is not 1683 but 1938 all over again. Prohibitions against mainstream religious symbols (minarets and headscarves) as well as less common practices (burqas, polygamy and forced marriages) are a harbinger of worse to come.

|

|

| Frost Over the World – Debating the face veil |

In reality, the relevant analogy is not 1683 Vienna or 1938 Berlin, but rather several crucial nation-building moments in between. In what are mundane but arguably critical domains for religious integration – such as mosque construction, the training of imams, chaplains, the availability of halal food and visas for the hajj – Muslim communities and European governments have begun to talk and to act in the Islam councils coming into existence across the continent. Thanks to the public nature of these consultations, Islam is no longer a black box to the general electorate.

This bears repeating in light of recent legislative efforts that adumbrate what Europeans already know well: Formal legal equality is not everything and emancipation is not irreversible. There is the growing danger that the modest accomplishments of religious integration will be undone before Muslims’ incorporation has taken place. Europe’s Muslims increasingly perceive the sum total of public debate about them as simple religious persecution – an uncanny admixture of the political distrust that drove the Kulturkampf and the religious resentment that fuelled traditional anti-Semitism.

In Germany, headscarf ban on public employees led one newspaper to run the headline “Mit Kopftuch nur als Putzfrau” (If you wear a headscarf, you can only be a cleaning lady), suggesting that the government was trying to keep Muslim women in menial labour positions. After the German high court’s decision to ban Muslim prayer in public school, one German Muslim federation said that authorities were “trying to drive the Islamic religion out of all public spaces”. The 1930s are also on the mind of Muslims elsewhere in Europe. Last year, a former presidential adviser in France called on fellow Muslims to start wearing a “green star” and when the French parliament considered a new headscarf ban, petitioners against the bill made explicit reference to the Nuremberg laws.

Self-defeating laws

The tide of restrictions shows little sign of receding. Their pursuit is too electorally rewarding – and too politically risky to oppose. This is a path on which many politicians find rewards, but it is on a slippery incline. Few observers contest the danger of Islamic fundamentalism or its deadly consequences. But if the obsession with Islamic symbols formed part of a coherent national security agenda, it would be complemented by trust-building measures in one of the few areas where the state has real power to influence outcomes, for example guaranteeing religious liberty under the rule of law. Instead, a disproportionate focus on cases of extreme piety or excessive religious modesty has produced one self-defeating legislative measure after another.

Take the headscarf and burqa restrictions that have been endorsed to date. Their implementation will impact directly only hundreds or perhaps thousands of families at most, less than one per cent of the many millions in the countries where parliaments passed them. The few women living under the weight of burqas in countries with new prohibitions, furthermore, will now be banished to their apartments. The handful of girls forced to choose between their faith and a public education will rarely encounter their non-Muslim peers in a neutral setting. As for discussions of restricting halal slaughter, this will affect little other than the ability of Islamic federations to raise funds locally. Suitable meat would just be imported and there would be no diminishment of the foreign cash needed to fund local religious associations.

Those who would impose limits on Islam’s presence in the public sphere have gone, in the space of a decade, from banning headscarves on behalf of women’s rights to the questioning of basic practices of religious toleration, such as the right to ritual animal slaughter, or the construction of houses of worship, with or without a minaret. In Milan, when the Deputy Mayor attended a Ramadan break-fast last August, she was accused by her predecessor of “sending the wrong institutional signal” and of seeking “equality for Islam as a religion”, which would lead straight to Sharia law.

While the best intentions of secularists, liberals, feminists or animal welfare activists are often at work in the formulation of these measures, their net effect is to sacrifice golden opportunities to impart republican values in a shared setting. And the impression remains that these advocates’ passions are less stirred by the illiberalism of non-Muslims. The pursuit of progressive social and political causes, such as women’s rights, animal welfare and free speech, can take on discriminatory overtones if they are not pursued with similar alacrity to bring reform to non-Muslim religious groups.

The wind and the sun

In July 1917, the former American president William Howard Taft gave a speech pondering the fate of Europe’s Jewish minorities as the United States joined the Great War. Calling for the unqualified emancipation of Jews and for their integration into every last national community in Europe, Taft warned that “harsh and repressive measures have not helped” and worse, are “always harmful”. Taft didn’t appeal to the legacy of Enlightenment or even the American and French Revolutions to bolster his argument. He cited Aesop’s fable of the contest between the wind and the sun in removing a man’s coat from his back. The harder the wind blew, the closer the man held the coat to his body. Likewise, Taft wrote, “persecution and injustice merely strengthen the Jew’s peculiarity in his adherence to his ancient customs, religion and its ceremonials”.

| Has multiculturalism failed in Europe? |

His solution amounts to a Victorian aphorism – persuasion is superior to force – but that does not lessen the wisdom of the 7th century BCE: “It was only when the sun with its warm rays increased the temperature and created discomfort that the man removed his coat.” Taft’s counsel continues to resonate today. Populist gesticulation around headwear, street prayer or halal food cannot substitute for serious strategies of socio-political inclusion.

If European leaders don’t step up to this challenge, finally, someone else will. There is a new pack of suitors on the continent. Qatar recently stepped into the French banlieues with a gift of €50m ($65m) investment and the courting of French Muslim elites. The ancestral nations of many European Muslims, especially Turkey and Morocco, have also intensified their outreach efforts. They’ve built elaborate institutions and consultative mechanisms of their own to stay in touch with and to protect what they consider to be increasingly vulnerable minorities. Even the US has developed programmes that aim to enhance the integration of European Muslims.

These other countries are wooing European Muslim elites into their orbits because they’re often the only ones taking them seriously. If things continue like this, European governments will waste the opportunity to capitalise on recent political sacrifices and progress made in the name of integration and regress to an era before they began to take responsibility for their own citizens.

Once all of the low-hanging fruit has been picked – the last burqa banned, the last foreign extremist deported – European governments will still need to raise their game and forge consensus on the far more critical and hard-to-reach goal: A coherent integration policy that engages full constitutional rights and responsibilities for all citizens. For now, party competition and unfavourable public opinion seem to have convinced many European governments that those grapes are sour.

Jonathan Laurence is associate professor of political science at Boston College and non-resident Senior Fellow in foreign policy at The Brookings Institution. He is the author of The Emancipation of Europe’s Muslims.