When Ann Coulter tells the truth

The notorious political commentator’s latest gaffe reveals a more gruesome, deep truth about conservatism.

|

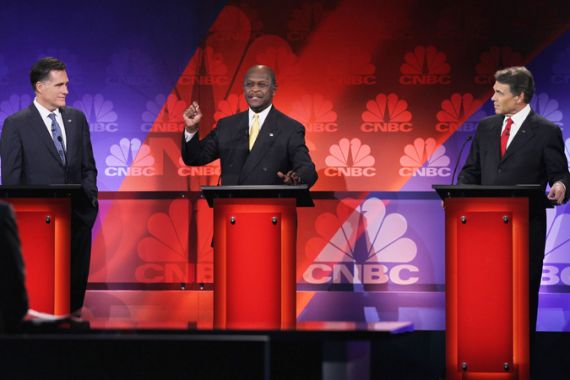

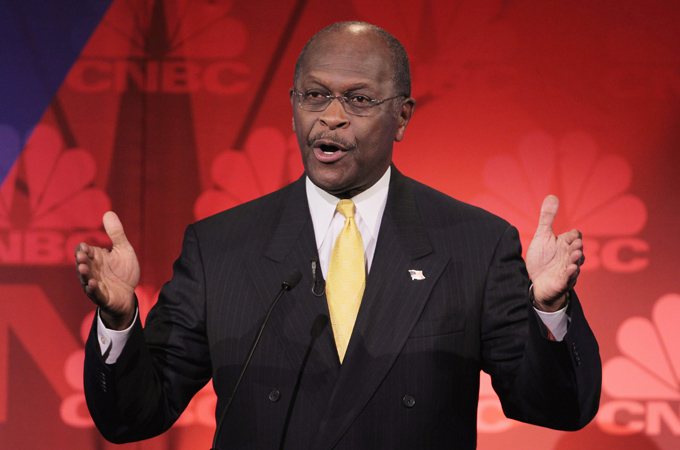

| Herman Cain, as a black conservative, must be more radical than his rivals to break through, argues Coulter [GALLO/GETTY] |

Everyone’s going after Ann Coulter – and rightly so – for her racist comments on the “Hannity” show. Asked why liberals and Democrats are up in arms over the sexual harassment allegations that have been levelled against GOP candidate Herman Cain, Coulter said:

“Our blacks are so much better than their blacks. To become a black Republican, you don’t just roll into it. You’re not going with the flow…”

That “our blacks” is especially gruesome. Sounds like the proprietary claim a fancy housewife would make, ca. 1960 (or 1860), about her black maid: “my girl” or something like that.

But if you can suspend disbelief – or disgust – for a minute, there’s something in what Coulter is saying that’s worth paying attention to, for it unwittingly reveals a deep truth about conservatism. Not its racism, but something else.

As I argue in The Reactionary Mind, conservatism has often attracted outsiders: Edmund Burke was not from Anglican and aristocratic England but from bourgeois and Catholic Ireland; Joseph de Maistre was not from France but Savoy; Alexander Hamilton was from the West Indies, the illegitimate son of a rumored biracial union. Benjamin Disraeli was a Jew, as was Irving Kristol. And on and on, from Leo Strauss to Phyllis Schlafly to Antonin Scalia.

Why has conservatism always relied upon the kindness of strangers? One reason is that the newcomer brings a particular angle of vision – how the privileged look from the bottom or the outside – that the privileged are incapable of getting on their own. The outsider helps the elite see not only how they look but how they might look if they change their ways. And that, as Tancredi reminds us in The Leopard – “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change” – is what conservatism is all about: changing everything so things, hierarchy in particular, can stay as they are.

But another, arguably more important, reason is that the outsider brings a scrappiness and moxie, an appetite for power and appreciation of privilege, that the inherited simply lack. As Burke himself was all too aware, when he unleashed a rage almost Jacobin in its substance and tone upon the Duke of Bedford, who had attacked Burke as a dishonourable and unscrupulous striver.

| “I was not, like his grace of Bedford, swaddled, and rocked, and dandled into a legislator; “Nitor in adversum” is the motto for a man like me. I possessed not one of the qualities, no cultivated one of the arts, that recommend men to the favour and protection of the great. I was not made for a minion or a tool… At every step of my progress in life (for in every step was I traversed and opposed), and at every turnpike I met, I was obliged to shew my passport, and again and again to prove my sole title to the honour of being useful to my country, by a proof that I was not wholly unacquainted with its laws, and the whole system of its interests both abroad and at home. Otherwise, no rank, no toleration even, for me. I had no arts, but manly arts.” |

Beyond the wounded sense of honour, Edmund Burke is laying out a matrix of the conservative claim to rule: the true man of power is not “swaddled” and “dandled” into his position; possessing only the “manly arts”, he wrests his position and assumes his place solely by the force of his wit and will. Such a man will, inevitably, not be to the manor born; he will spring from society’s lower orders. In such men (and sometimes women), conservatism has always rested its hopes.

You might think, to the conservative mind, that Barack Obama would be just such a man. He came from inauspicious beginnings, and by virtue of being the first black man to win the presidency, he’s certainly proven his mettle. But Barack Obama rose to his position the old-fashioned way. He worked hard, studied hard, and made sure to dot his ‘i’s and cross his ‘t’s as he made his way through the antiseptic halls of the US meritocracy (Columbia, Harvard, and beyond).

The conservative vision of ascent is rougher around the edges. The outsider who becomes a right-wing insider must not sail to power on his SATs; he must claw his way to power like Tony Soprano. He has to show that he understands the darkness of the American Dream, that you have to fight – and fight dirty – for your position.

That’s why Coulter formulates the virtues of Cain as she does: unlike black liberals or Democrats, the black conservative doesn’t roll into his opinions; he fights his way into them. He doesn’t go with the flow; he stands in the crashing surf, forcing the waves to break. That is his claim to power, his entitlement to rule.

It’s also why the New Canaan-born Coulter would look to Cain for a glimpse of the Republican promised land – however much her racist rhetoric betrays the fact that she’s still in Egypt.

Corey Robin teaches political science at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. He is the author of The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Sarah Palin and Fear: The History of a Political Idea. His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Harper’s, the London Review of Books, and elsewhere. He received his PhD from Yale and his A.B. from Princeton. You can read Corey’s blog here and follow him on Twitter @CoreyRobin.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.