What a difference a decade makes

Bin Laden succeeded in dragging the US into endless, expensive wars – however he lost the attention of the Arab world.

|

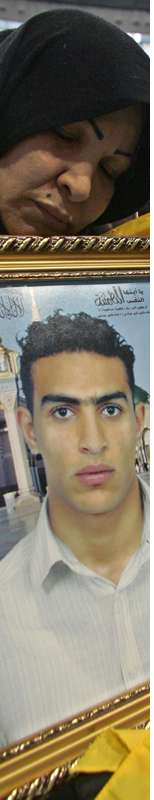

| ‘Bin Laden clearly lost the bigger war, for the soul of the Arab world he unleashed forces that produced thousands of revolutionaries’, writes Mark LeVine [EPA] |

Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia: If someone had told me on the morning of September 11, 2001 that ten years later to the day I’d be standing in a city named Sidi Bouzid at the spot where a man launched a revolution that toppled dictators across the Arab world by setting himself on fire, I would have told them to go see a psychiatrist.

It was a good morning, at least the first hour of it. Having just finished breakfast, I was just opening up some sheet music for a project I was recording with some world musicians in France – Palestinians, Israelis, Lebanese, Italian, Turkish and French; we were a motley crew of musical vagabonds trying to actualise the idea of global society that was still more myth than reality less than a year into the new millenium.

I was happy to escape the chaos and delirium of my new-born son for a few minutes and focus on my music, until the first call came.

The rest is, quite tragically, history. Yet here I am, a decade after watching the second tower collapse across the East River with my son in my arms, staring at a non-descript piece of asphalt on top of which Mohamed Bouazizi initiated his act of self-immolation, igniting the Arab Spring along with him.

There is no memorial or flowers to mark the spot (although across the street and down the block there is plenty of graffiti). Perhaps it’s unnecessary; Mohamed Bouazizi’s life has grown so large that, like the spot where the universe first came into being, it no longer matters precisely where it all began.

What a difference a decade makes.

|

In the weeks after the attacks of September 11, it seemed that the United States was becoming very quickly like Israel; both countries suddenly shared two frightening commonalities: the death of any sense of ordinary security and the lack of honest introspection about policies that produce hatred and violence. Of course, those who attacked it had to be tracked down and punished, even killed. But at the same time, Americans needed to take a cold hard look at “why they hate us” – the title of the first issue of Newsweek after the attacks.

Of course, we never did this. Instead, President Bush reassured a frightened nation that “they hate us for our freedoms”, even as the Pentagon explained that they hate us much more for our policies.

The US is still embroiled in Iraq and Afghanistan, with no end in sight for either occupation. And while once a invincible superpower was otherwise occupied – just as happened to Israel, America’s occupations ultimately led to its own occupation by an out-of-control war-as-security machine – the winds of history moved on.

Not to China, which everyone saw as the next great opponent to the American neoliberal model of economic, political and social organisation. Nor to the once vaunted European Union, which shrivelled politically, andultimately economically, under the weight of a global system caught between American hyper-militarism and Chinese hyper-industrialisation.

Instead, as the decade drew to a close, it was the Arab world to which history returned, sparked not merely by Mohamed Bouazizi’s desparate act, but by an entire generation that he represented, from Morocco to Syria,

who’d finally had enough, took destiny into their hands, and literally changed the course of history in ways the rest of us, and they, are only just beginning to understand.

|

| Bouazizi’s act of self-immolation was the metaphorical straw that broke Ben Ali’s back[EPA] |

A universal consciousness

As with most great historical processes, the event that is most often credited with sparking the so-called “Arab Spring” – Bouazizi’s self-martyrdom – was in fact only one link in a much longer chain of events that has produced the radical changes the world is presently witnessing unfold. In the working class neighbourhoods of Sidi Bouzid where Bouazizi lived and died, his sacrifice is considered no more important for most people than that of his friend Hussein Lahsin Neji.

Several days after Bouazizi’s act, Neji went to a protest at the local offices of the UGTT, Tunisian’s state-sponsored union, snuck behind a police line, climbed to the top of an electricity pylon, and electrocuted himself in protest against the system which had done nothing to recognise the meaning of his friend’s suicide.

In the weeks and months since their deaths (and they were preceded and followed by other, lesser known suicides), all sorts of phrases and intentions were attributed to them and the protesters who took to the streets in defense of their memory. Bouazizi is supposed to have shouted “shughul, huriyya, wa karama wataniyya!” – “work, freedom and national dignity”, as he took his final steps, while the chants of the protests that grew in the wake of their deaths marked the first appearance that most people here can remember of the now celebrated demand, “The people want the downfall of the system”.

But even these actions and slogans were not merely spontaneous bursts of political genius; rather they were the result of a “deep wave” of societal maturation, which saw a new generation come of age in Tunisia, and in fact across the Arab world, who was no longer afraid of its aging and increasingly out of touch leaders.

“This was a wake up of universal consciousness”, explained Muhammad Nouri, an engineer and economist from Sidi Bouzid, as we had coffee in Sidi Bouzid’s main hotel, the Ksar Dhiafa. Nouri established a grassroots think tank, The Center for Strategic Studies and Development, in his hometown only three days after Ben Ali fled the country.

Not content to let the capital Tunis or the rapidly expanding national political organisations take the lead, I caught Nouri leading a group of several dozen residents of the town, at least half of them in their late teens or early twenties, through what he described as a “revolutionary school” intended to help strengthen local civil society in the lead-up to the coming elections. Their goal is to retain a strong measure of citizen control over whatever government emerges after the elections.

For Nouri and most every activist I know, the key development that enabled the revolution in Tunisia was, as the American sociologist of non-violence Gene Sharp predicted almost four decades ago, the emergence of a new generation that no longer feared the system that oppressed it. This process began sometime in the middle of the last decade, when friends of mine began to notice students starting to talk openly of their hatred for Ben Ali and his regime in the classroom. Some even “dared to dream of how to take down the system”, as one young activist described conversations with her friends.

A generational shift was occurring, the importance of which did not register on most people until the “jil al-jadid”, or New Generation, had thrown off the shackles that held down its parents.

“It wasn’t Sharp who taught us about overcoming fear, but the same spirit that inspired him ultimately reached us,” Nouri went on. “The thing that the Tunisian revolution brought which was new in the Arab world was our realisation that the power of those who are ruling us, and ruling the world, is based on only one thing – our fear. We discovered that if we overcome this fear, they have no power. That’s what we gave Egypt.”

Self-organisation

In Egypt this rise of a new consciousness was perhaps less spontaneousthan in Tunis. Activists from the labour movement and a far more developed civil society arena had in fact spent the latter half of the 2000s purposefully laying the groundwork for that country’s revolution, through increasing cooperation and training of crucial groups that would help

organise or direct the uprising.

But in Tunis the revolution occurred much more as an act of spontaneous self organisation. One young activist, Sabeur, explained as we stood across the street from where Naji electrocuted himself, “There were never any meetings, no attempt at organisation. If anyone form the unions or parties say there was organisation that’s a lie. We organised ourselves. What did we need training for, to fight the cops? Throw rocks? If you want to be a patriot or revolutionary you become one immediately, you don’t have to train.”

It is perhaps the self-organisation that so confused the Ben Ali regime, which like its counterpart in Egypt had grown so out of touch and so arrogant that it was literally asking to be removed. Whether it was the result of increasing coordination and strategic maturity or self-organisation, both Tunis and Egypt proved that ordinary citizens could take on not merely an oppressive ruler, but the larger global system that backed them to the hilt, and win, at least for the moment.

The fight is certainly not over. Here in Sidi Bouzid many activists are increasingly scared of the growing power of what they refer to as “the Salafis”. According to some activists, Salafists have have forcibly taken over one of the town’s main markets and threatened shopkeepers selling “un-Islamic” clothes or alcohol.

But however bullying they may be to their less orthodox neighbours, the Salafis are only one of a host of parties and groups present in Sidi Bouzid and around the country – I doubt even the most imaginative Tunisian would have dreamt that one day the office of the Nahda Party would be across the hall from the Tunisian Baath Party, both legal and open for business

|

“Young activists are defying the secular/religious and other dichotomies of the old system” |

And young activists are defying the secular/religious and other dichotomies of the old system by working together to build a common, if still fragile future. Together with the artists, musicians, intellectuals and ordinary citizens who made the Arab Spring and Summer possible, they created melodies, harmonies and now full-blown symphonies whose swing and rhythms my musical comrades and I couldn’t have imagined on Sepember 10, 2001.

Whither the next ten years?

Which brings us back to the United States. To say it’s not been a good decade is an understatement of gross proportions. And as in 2001, the fortunes of the US in the eyes of the Arab world remain tied inextricably to the actions of its main ally in the region, Israel.

As the clock strikes midnight here in Sidi Bouzid, Al Jazeera Arabic is continuing to devote its full attention to the attack on the Israeli Embassy in Cairo. Throughout the day, the network has devoted as many as four split screens linking Tel Aviv, Cairo and Doha. Images of the protests there inevitably show Israeli and American flags placed next to each other, as protesters see no difference between the policies of the two governments.

Even Tunisia’s leading human rights campaigner, Mokhtar Trifi, spent the majority of an interview on Al Jazeera discussing not the unprecedented conference his organisation, The Tunision League for Human Rights, held on

Friday, but rather why the situation in Palestine is an important and legitimate human rights concern for the Arab world, and the world at large.

Osama bin Laden might have succeeded in bleeding the US dry, his ultimate aim when he launched the operation that destroyed the World Trade Center and thousands of irreplaceable lives with it. But it was the brutality and thoughtlessness of America’s response that cost it the sympathy of so many in the Arab world, for whom the 10th anniversary of September 11 is ultimately irrelevant for their lives (“the same number of people died in Iraq every month”, declared one young activist. “Look at Gaza”, declared another).

On the other hand, bin Laden clearly lost the bigger war, for the soul of the Arab world. In turning the might of the US directly against the region, he unleashed forces of resistance to the entire system that, while producing thousands of jihadis, produced millions of revolutionaries. They have made him as irrelevant as has become United States to their hopes, dreams and plans for the future.

Bin Laden’s irrelevance could have been the ultimate victory for the United States, a true silver lining of the monstrous cloud of 9/11, had it not squandered the good will that accrued to it in the ensuing decade. Now as Americans are finally forced to reckon with the costs of the last decade of violence and erosion of liberties perpetrated in their name, perhaps we can imagine a new generation sitting in their classrooms and cafes right now, daring to contemplate the “downfall of the system” that was built in large measure on the fear, ignorance and arrogance of their elders.

We can’t predict what might be the spark for a new American Revolution. But considering the damage a slowly dying American Empire will inflict on the planet merely through its inability to wean itself from the addictions that brought it to the brink, even the most tired Arab revolutionary would do well to take a minute to consider how they can help Americans embrace the consciousness that has so energised their societies during the last year.

Not even time will ease the pain of those who lost loved ones so horrifically on that brigh blue September morning a decade ago. But if such a transformation could begin, Americans as a nation, and the world as a whole, could finally begin to heal.

Mark LeVine is a professor of history at UC Irvine and senior visiting researcher at the Centre for Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University in Sweden. His most recent books are Heavy Metal Islam (Random House) and Impossible Peace: Israel/Palestine Since 1989 (Zed Books).

You can follow Mark LeVine on twitter @culturejamming

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.