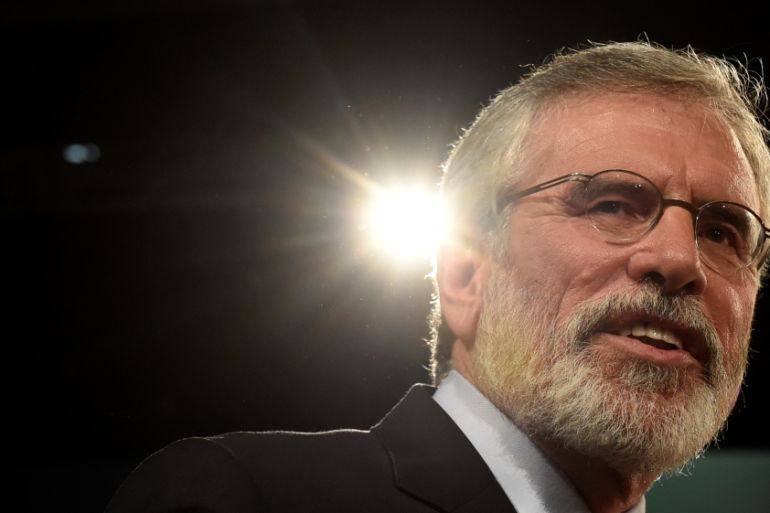

Gerry Adams: A significant figure or cult leader?

As Sinn Fein leader prepares to step down, Adams leaves behind a legacy that continues to divide opinion.

In 2005, Gerry Adams went to South Africa. After landing in Johannesburg, he laid a wreath at Freedom Park before driving to the University of Witwatersrand to make a speech.

At that point, he’d been the leader of the Irish nationalist party, Sinn Fein, for 22 years. It was a party Nelson Mandela described as “an old friend and ally”, and this was one of several visits to South Africa by Gerry Adams that aimed to burnish his moral credentials as a peacemaker.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsGermany’s AfD bans top candidate from EU poll events over Nazi comments

Iran’s Khamenei leads prayers at Raisi memorial before tens of thousands

Vietnam’s security chief To Lam becomes new president

Waiting at the university was a BBC journalist who had scheduled an interview with the politician, and was struggling to find an interesting angle on a story about a man made famous in a conflict that had long since ceased to be “top of the bulletin” material.

The interview started politely as Adams related his time in South Africa, and then the BBC journalist changed tack. Pointing to the African National Congress’ (ANC) largely peaceful overthrow of the apartheid regime, he asked Adams if he felt Mandela’s party enjoyed a kind of moral legitimacy that Sinn Fein never would.

![South African President Nelson Mandela meets with Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams in 1995 at the African National Congress headquarters in Johannesburg [Juda Ngwenya/Reuters]](/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/2af8c6073e334a8fa49b5e130de87cf8_18.jpeg)

He was, of course, referring to Sinn Fein being the political wing of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), an organisation responsible for killing more than 1,700 people.

It was an abrupt and unwelcome confrontation between two sides of Adams’ persona, two epochs of his life: the defender of violence, and the man of peace. The politician responded by suggesting bias on the part of the BBC; the interview went cold, ended awkwardly, and was never broadcast.

Adams will soon step down as leader of Sinn Fein after 35 years at the helm. In that time, he has catapulted the party out of political obscurity.

Last year, Sinn Fein came within one seat of shredding the domination of pro-British political parties in Northern Ireland, a feat that could very well have resulted in a referendum on ending British rule there.

This success was built on the back of a negotiated settlement that ended 30 years of sectarian violence in Northern Ireland, a settlement in which Gerry Adams played a large part. As political resumes go, it’s an impressive one.

A ‘significant’ figure

Former IRA man Tommy McKearney is not a cheerleader for Adams. Nonetheless, he describes him as “one of the most significant major figures in Irish political life over the last 40 years, whether one likes or dislikes him”.

Adams’ significance comes from him having persuaded the IRA to give up the use of armed force and to replace it with constitutional politics to achieve a united Ireland. This is a point even his unionist opponents acknowledge.

Ben Lowry, deputy editor of the Northern Irish unionist daily newspaper, the News Letter, says: “He definitely steered the IRA, over a long period of time from the early 1980s until the late 1990s, away from violence.”

Born into a poor family in west Belfast in 1948, Adams became involved in nationalist politics in the 1960s.

![Gerry Adams with Christy Burke, Sinn Fein's candidate in Dublin Central, in 1983 [Independent News and Media/Getty Images]](/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/79ca2363265a491aacacd03b1ea92679_18.jpeg)

By his early adolescence, Northern Ireland had been run for 40 years by the Ulster Unionists, pro-British and almost entirely Protestant.

Injustices against Catholics, including discrimination in the allocation of housing and unequal voting rights, gave rise to the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Movement. Adams signed up to the organisation in 1967.

Two years later, a cocktail of political turmoil pushed this small region of the UK, containing just 1.5 million people, over a cliff.

Sectarian rioting between Catholics and Protestants in Belfast and Londonderry prompted a plea from the government for British troops on the ground. The troops were at first welcomed by Irish nationalists and Catholics as protectors, but quickly became the target of IRA gunmen, who saw them as illegitimate enforcers of British occupation.

The decades-long conflict that followed saw the Provisional IRA emerge as a deadly force that killed thousands of policemen, soldiers and civilians, as well as senior figures in the British government, almost claiming the life of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Deadly hunger strikes

Gerry Adams spent the 1970s being variously interned and arrested for alleged IRA activity but has always denied being a member.

It was the events of 1981 that gave rise to his political career.

That was the year that 10 IRA prisoners starved themselves to death, using a hunger strike to demand political status that the British government refused to grant.

The outpouring of emotion that followed encouraged the Sinn Fein leadership to seek an electoral mandate that would back up their claims of widespread support for British withdrawal and Irish unification.

They would proceed, in the words of one activist, “with a ballot paper in this hand and an Armalite in the other”.

![Martin McGuiness and Gerry Adams pictured in 1985 [Independent News And Media/Getty Images]](/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/dd04213287b14b79b441b92189861187_18.jpeg)

Adams took over the leadership in 1983 and put that strategy into action.

McKearney was one of those who participated in a lesser known hunger strike in 1980.

Adams, he says, did not conceive of the strategy independently, but cultivated it and persuaded others.

“The argument was being made through the 80s that there had to be an alternative,” he says. “The IRA, Sinn Fein and the republican movement, in general, has a political objective, and decisions were made pragmatically and rationally about how best to advance that political agenda.

“Once it was deemed important to defend that position with arms and then the decision was taken to move away from arms, it wasn’t useful any longer, and the movement was persuaded of that by Gerry and others.”

What began as a dual strategy evolved over the course of the 1980s into a view among many in Sinn Fein that continued violence was pointless.

Some of this was likely motivated by the very successful efforts of British intelligence to undermine the IRA through a network of informers.

McKearney does not refer to this, but does describe the British state as a “very strong and determined enemy”, and admits that “some options were closed down and others opened up”.

Something of a window of opportunity for peace negotiations was opened in the 1990s. By the end of that decade, Adams and his colleague Martin McGuinness had persuaded their party to enter into an agreement that would eventually see the IRA end its armed campaign and decommission its weapons in return for the release of prisoners and political representation in the government of Northern Ireland.

Gerry Adams, a man whose voice had been banned on British television four years earlier, now occupied an office in Stormont, formerly the seat of unionist power.

But observers point to a contradiction in that success. How, they ask, could Adams have so successfully controlled a notorious paramilitary group of which he has consistently denied ever being a member?

Since the peace agreement in 1998, Adams has been plagued by accusations from unionists and nationalists alike that he not only joined but helped to lead the IRA in the worst years of Northern Ireland’s violence.

In 2014 he was questioned for four days by Northern Irish police in connection with the 1972 murder of a single mother of 10 children. He was released without charge.

‘He can’t tell the truth from lies’

There are those who excoriate Adams’ record, and among them is former IRA member Shane Paul O’Doherty. Since spending a decade and a half in jail for his part in a letter-bombing campaign, O’Doherty has renounced violence entirely.

He calls Adams a “strategist, full of charisma, a great cult leader, he has people who will follow him to hell”, but, he says, “at this stage in his career [he] can’t tell truth from lies”.

Editor Lowry says: “Because of the violence, and the horrors that happened, and although he denies having been in the IRA, he’ll never be forgiven by the unionist community”.

Adams’ characteristic opacity has fuelled speculation over his past. He is, says Lowry, “mysterious, hard to read, inscrutable”. For unionists, that’s disconcerting, especially since Adams is a man who gets results; for those who support him, it breeds respect.

Because of the violence, and the horrors that happened, and although he denies having been in the IRA, he'll never be forgiven by the unionist community.

Even in the twilight years of his political career, Adams has continued to evolve and grow in stature.

He gave up his place in Northern Ireland’s assembly to campaign for and win a seat in the Dail – the elected legislature of the Republic of Ireland. Sinn Fein is now the third largest political force in the Republic.

The party’s future lies in consolidating its position on both sides of the Irish border; a future bought for it by the leadership of Gerry Adams.

Most commentators believe Adams will remain an essential figure to his party behind the scenes, inhabiting a perhaps familiar position, in the shadows.