US drone revelations: Meaningful or business as usual?

Al Jazeera asks what the release of Obama’s 2013 drone playbook and new executive order mean for those most affected.

The release of President Barack Obama’s 2013 drone warfare playbook and the July 1 signing of an executive order on minimising civilian casualties has security analysts looking back at previous strikes and wondering what effect the executive order might have on future ones.

Obama’s 2013 policy guidance, released on July 31, after the American Civil Liberties Union sued for its release, had set “near certainty” that a “terrorist target is present” and that “non-combatants will not be injured or killed” as criteria for a strike.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhat happens when activists are branded ‘terrorists’ in the Philippines?

Are settler politics running unchecked in Israel?

Post-1948 order ‘at risk of decimation’ amid war in Gaza, Ukraine: Amnesty

These developments might, although this remains to be seen, reduce scenes such as the one at a May 23 State Department press briefing, when its spokesman Mark Toner seemed short on basic details about the strike that killed Taliban leader Mullah Mansoor:

Q: So you don’t know where you targeted him? You just guessed? I mean, how could you fire something out of the sky and blow something up and kill people and not know what country it’s in? Come on.

TONER: [laughing] I understand what – your question, Brad. All I’m saying is what we’re able – I said what we’re willing to share is that it was in –

Q: You check these things before you fire, usually, right?

TONER: – the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region. We certainly do.

There have been questions about the precision of these strikes – a 2015 investigation by The Intercept news site revealed that nearly 90 percent of people killed in US drone attacks in Afghanistan alone were not the intended targets.

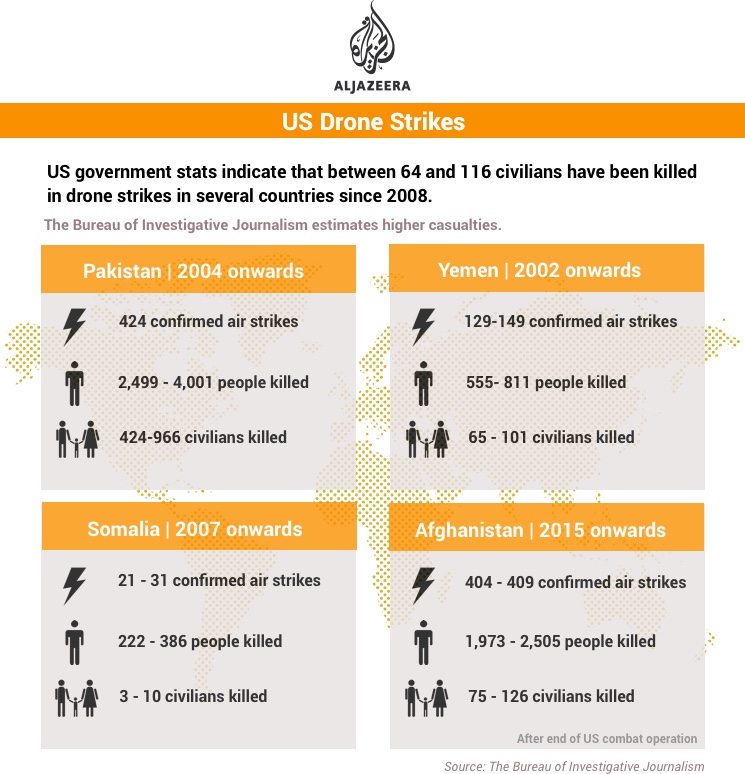

James Clapper, the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), in July released the DNI’s tally of civilian drone deaths. It estimated that since Obama took office in 2008, between 64 and 116 civilians have been killed in Yemen, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia and other areas where the US is not actively engaged in war, and that there have been 2,372 to 2,581 combatant deaths in the same countries.

But anti-drone activists criticise the drone programme’s lack of precision, especially in Waziristan, the heavily targeted region between Afghanistan and Pakistan, where rights groups estimate that hundreds of civilians have been killed. Clapper offers reasons for the discrepancy between his tally and those of rights groups, suggesting rights groups fall prey to “the deliberate spread of misinformation by some actors, including terrorist organisations, in local media reports on which some non-governmental estimates rely”.

‘My relatives were killed’

What difference will the release of the playbook and the signing of the recent executive order – which calls for greater safeguards and oversight in drone strikes – make to people in countries such as Yemen, Pakistan, Somalia and Afghanistan, where thousands of civilians have been killed over about a decade?

“The executive order and the playbook don’t mean very much to me – both talk about targeting and ‘lawfulness’, but the bottom line is that my relatives were killed in a strike despite never having done anything wrong, and I’ve never been given an explanation as to why,” said Faisal bin Ali Jaber, whose nephew and cousin were killed when a US drone struck a wedding in 2012 in Yemen’s Khashamir village.

|

|

| UpFront:The truth about US drone strikes |

His is among the families who have been given cash as compensation. But what Jaber wants is an apology.

“I was disgusted that this was being offered in place of an apology, and justice,” said the 58-year-old.

“Since my relatives were killed, many more innocents have died in US drone strikes. Despite all the talk of targeting and strikes being a ‘last resort’, the American government still seems to be making these strikes without having any clear idea of who they are killing,” said Jaber.

“What is needed is an end to the strikes, and acknowledgement of the deaths of innocents they have caused.”

Shahzad Akbar, the director and founder of the Foundation for Fundamental Rights, says the release of the redacted 2013 document, which provides guidance on the use of “direct action against terrorist targets” overseas does not mean much “to ordinary Pakistanis who have already lost loved ones”.

“[The playbook] doesn’t really mean much to people on the ground … It is nothing, because it’s not addressing the wrong that has been done to them … that is something that no one has touched,” said Akbar, whose foundation represents roughly 300 families who have been affected by drone strikes in Pakistan.

Even the executive order, said Akbar, only “binds the future president, not President Obama himself – there’s no accountability of his own actions”.

“When President Obama accidentally kills two Westerners, white people, in drone strikes, they go all out … he apologises on TV … But hundreds of other non-white, non-Westerners have been killed, and not a single person [in Pakistan] has been apologised to or compensated. What could that person feel? Why would that person be a stakeholder in any society that we’re trying to build? Because you’re not even recognising his existence.”

Still, Akbar is open-minded about the potential for the executive order to change future US drone strikes.

“In one way it is good, because he [Obama] himself, being a constitutional lawyer, realised the current situation, in how much latitude it gives to the intelligence agencies, like the CIA, to get into the act of killing outside war zones basically with full impunity … therefore he’s putting in some checks, but what this executive order lacks is accountability,” said Akbar.

Fear of reprisal

In a place like Somalia, there is seldom a question of accountability at all. There, US drones have been striking al-Shabab territory for years. Civilians caught in the crossfire rarely dare to speak up even domestically, let along ask the US for accountability.

The UK-based Bureau for Investigative Journalism reports that since 2007 between three and 10 Somalis have been killed in confirmed drone strikes, with as many as 47 killed in other covert ones.

Somali journalist Omar Faruk Osman, who has reported on drone strikes in his country, told Al Jazeera that if the families of civilians killed by drones protest, they will be accused of being al-Shabab sympathisers.

“They have a fear of reprisal – they don’t talk to lawyers or even to reporters … and nobody talks to them about these reports and executive orders,” said Osman.

“Most live in areas without media … they don’t even have a community radio station, so these things [the promises of protections, transparency and accountability] don’t even exist to them,” he said.

Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, a lawyer at Reprieve who assists drone victims, told Al Jazeera that the release of Obama’s 2013 drone directives stops short of justifying civilian deaths to the families of the victims.

“Only at the tail end of the Obama administration, after fighting for years in the courts to keep this information secreted away from the American public, do we get to see the rules the government has written describing when and how it decides to assassinate people,” said Sullivan-Bennis.

“The administration cannot laud itself for transparency when such transparency can only be wrestled from it via years of litigation.”

A White House statement accompanying the July 1 executive order catalogues the best practices the US government currently implements, “including acknowledging US government responsibility for civilian casualties and offering condolences, including ex gratia payments, to civilians who are injured, or to the families of civilians who are killed; and, when civilian casualties have occurred, taking steps to minimise the likelihood of future such incidents”. The 2013 playbook, meanwhile, says that in its fight against “the terrorist threat posed by al-Qaeda and its associate forces”, the US will uphold American “laws and values”.

Those values remain unproved to people such as Faisal bin Ali Jaber.

“I thought that the US stood for justice, truth, transparency, and respect for civilian life,” he said.

“I have been deeply shocked by what I’ve experienced at the hands of the US government.”

Follow D. Parvaz on Twitter @dparvaz