Cambodia’s illegal healers say they serve the poor

Unqualified medics were outlawed after one infected villagers with HIV, but many cannot afford any other treatment.

Roka, Cambodia – Mao Sophan was pregnant with her third child when she came down with a fever.

Weak and exhausted, she went to the local village healer, a short walk from her wooden hut in Roka, a remote village in Cambodia’s northwest.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsSouth Africa’s Ramaphosa signs health bill weeks before election

Gaza lost much more than a hospital when it lost al-Shifa

With measles on the rise, rebuilding trust in vaccines is a must

Yem Chhrem gave her two intravenous drips and she soon began to recover. Little did she know that this treatment would have tragic consequences.

“I’m very angry with the doctor,” Mao, 31, says. “If he came near me now, I would chop him up.”

Mao was one of about 280 villagers, from babies to the elderly, who contracted HIV after the unlicensed doctor used contaminated needles.

After the outbreak, the government banned unqualified medics from treating patients, threatening them with jail and fines.

But in a country with only one qualified doctor for every 5,000 people – one of the world’s lowest ratios – many poor Cambodians have little choice.

With Cambodia’s health system severely under-funded and lacking qualified staff, village healers say they provide a vital service.

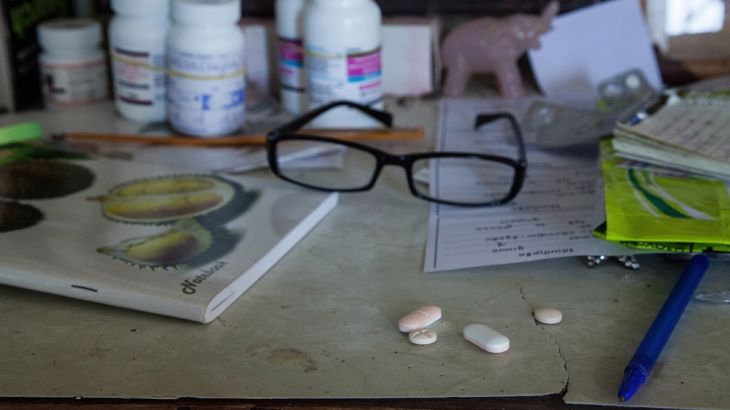

![HIV medication is seen on a table inside a house in Cambodia [Omar Havana/Getty Images]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/905e9538f8c84808bb7f66533b25ea37_18.jpeg)

‘I still want to help people, but the law doesn’t allow it’

Chek Cheoum, an unlicensed doctor who lives in a village a few hours’ drive from Roka, knows what he’s doing is illegal. But he says saving lives is more important.

Like many unlicensed doctors, he was a military medic under the Khmer Rouge, but he never attended medical school.

“People in this village are very poor,” he says. “Some can’t even afford a bicycle or the $1 it costs to travel to a health centre. They ask me for help. Sometimes they don’t pay because they don’t even have enough to eat.”

Concerned that he could be jailed if found treating patients, Chek has decided to stop practising once he uses the last of his medical supplies, which he carries around in a black plastic bag.

He has decided to become a farmer, but he is upset that he is no longer allowed to treat patients.

“I’ve never had any problems. Nothing bad has ever happened to my patients. That’s why people keep coming back,” he says. “In my heart, I still want to help people but the law doesn’t allow it.”

Some unlicensed medics have already stopped seeing patients. Term Touey, who lives in a village not far from Chek, performed surgeries on villagers until a few months ago.

“I worry about the sick who have no money and still come to me. This makes things very difficult,” he says.

‘People still need my services’

Term was recruited by the Khmer Rouge when he was 11. He trained as a medic during the 1980s and performed many amputations on landmine victims at a refugee camp hospital.

Now he is frustrated that he can no longer treat patients. “People still need my services. They make a difficult journey to see me and refuse to leave. But I’m afraid there will be complaints. I really want to treat them. I was born to treat people,” he says.

“I’m frustrated that I have the knowledge, yet I am not allowed to practise. Because of one careless doctor, people like us are facing a lot of problems.”

Despite the risks associated with unlicensed medics, some registered doctors say that they understand why many Cambodians, especially the rural poor, rely on them.

Dr Kuch Kam San is a licensed doctor who heads a medical team run by a non-government organisation called The Lake Clinic on Tonle Sap Lake, the largest freshwater lake in Southeast Asia.

Travelling by boat with a team of nurses and midwives, he treats some of Cambodia’s poorest and most remote communities who live in floating villages, far from hospitals.

It’s a vital service but the team can only treat a fraction of the three million people who live around the lake.

Kuch says he understands why villagers turn to local healers, even if they are not formally trained. “They use their services because we are not here all the time,” he says.

Back in Roka, Mao Sophan, the young woman who contracted HIV, says she knew that the village healer, Yem Chhrem, was unlicensed, but he was close by and she could afford his treatment.

“If people had no money, they could always get a jab from him. They could pay four or five days later,” says Mao. “Every time we needed him, he would show up.”

‘We must keep going whether dying or alive’

Yem is now serving 25 years in prison. Since the HIV outbreak was discovered in 2014, at least 14 people have died.

After she discovered she was HIV positive, the government gave Mao free anti-retroviral drugs and her daughter was born healthy.

But she is struggling to deal with the side-effects of the medication. “I’m always shaking because I don’t have enough to eat. Sometimes I can’t even stand up but I have to try,” she says.

Mao and her husband had to sell their rice field when she became too weak to farm. “I’m depressed. I have the HIV virus and all I think about is death,” she says.

Now the couple travel three hours by motorbike into the forest to harvest wild vegetables to sell. She says she and her husband must keep working because there is no one else to look after their three young children.

“We must keep going whether dying or alive … and try not to think too much,” she says. “If we don’t do this, we’ll starve.”

From the 101 East documentary “Cambodia: Unlicensed to Heal.” Watch the full film here

Follow Chan Tau Chou on Twitter @tauism101 and Liz Gooch on Twitter @liz_gooch