Poisoned spy inquiry reignites British-Russian tensions

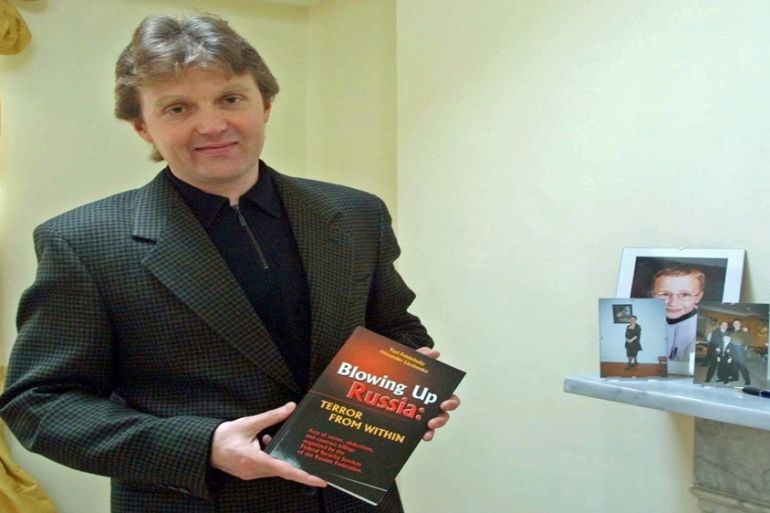

Inquest into the 2006 nuclear-poisoning of ex-Russian spy continues with Alexander Litvinenko’s wife testifying.

London, United Kingdom – Inside the leafy confines of the gothic hilltop Highgate Cemetery lies the tomb of London’s most famous refugee, philosopher Karl Marx. But for the last eight years it has also been the final resting place of fellow exile Alexander Litvinenko – the man at the centre of one of the most notorious murder cases in modern history.

In 2000, Litvinenko with his wife Marina and son Anatoly arrived at London Heathrow Airport, immediately approached a policeman and claimed asylum on the grounds that his whistle-blowing about the crimes of his former FSB (formerly KGB) superiors had made him a target.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Regime machinery operating efficiently’ as Tunisia cracks down on dissent

Why Egypt backed South Africa’s genocide case against Israel in the ICJ

US sanctions two RSF commanders as fighting escalates in Sudan’s Darfur

Years later, on the fateful day of November 1, 2006, Litvinenko met with two Russian businessmen, Dmitry Kovtun and Andrei Lugovoi, at a central London hotel bar.

You may succeed in silencing me but … the howl of protest will reverberate, Mr Putin, in your ears for the rest of your life.

That evening he became violently ill, three weeks later he died in agony.

On Monday, Marina Litvinenko addresses the public inquiry in London to tell what she knows about her husband’s murder.

Political revenge?

It was revealed the cause of Litvinenko’s death was acute radiation poisoning by the rare radioactive isotope Polonium-210. Photos of an emaciated 43-year-old Litvinenko were beamed across the world and a deathbed statement read out in which he blamed Russian President Vladimir Putin.

“You may succeed in silencing me but … the howl of protest will reverberate, Mr Putin, in your ears for the rest of your life.”

The start of last week’s hearing at the Royal Courts of Justice marked the culmination of an eight-year legal campaign by Marina Litvinenko to get the government to open a public inquiry into her husband’s death.

An initial inquest was deemed unsuitable by Chairman Sir Robert Owen as it would not allow for crucial, yet sensitive, national security information to be heard. In 2013, Home Secretary Theresa May admitted the intransigence was in part an effort at maintaining diplomatic relations.

Once in London, the court heard, Litvinenko adopted the alias Edwin Carter, kept the company of the capital’s growing ranks of exiled oligarchs, Chechen politicians and ex-spies, and became a strident critic of Putin.

He also reportedly began working with the British intelligence agency MI6. Ben Emerson, a lawyer for the Litvinenko family, posited the spy was killed in “political revenge” as a “lethal deterrent” to other whistle-blowers, and for his investigations into alleged links between the Kremlin and organised crime syndicates.

Radioactive suspects

Shortly after Litvinenko’s death, British authorities named Lugovoi – and later Kovtun – as the chief suspects after scientists discovered a snail trail of radiation contamination all around the city.

Nuclear weapons expert Dr Igor Sutyagin – currently a Senior Research Fellow at London’s Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies – had been imprisoned in Russia for more than a decade on accusations of espionage until 2010. He denies the spying allegations.

“Polonium does not leave any trail if you handle with care and act professionally … it disappears after use. If they had got it right, there would not have been a trail behind Lugovoi. The signature of the Soviet security services was to use untraceable poisons, and Polonium is approximately 2.5 million times more poisonous than cyanide,” Sutyagin told Al Jazeera.

On the first day of the inquiry, the court was told the suspects had tried to poison Litvinenko on at least one other occasion in mid-October, at an office.

Eerie diagrams of the hotel rooms where Kovtun and Lugovoi had stayed were shown with colour coding splashed across the furniture indicating levels of detected radiation.

The spout of the tea pot from which Litvinenko drank glowed purple – the highest level. The nuclear expert witness referred to as “Scientist A1”, to protect her identity, testified that, “It is more than probable that this was the primary source of contamination.”

Despite having found only a “sub-microscopic” amount of Polonium in Litvinenko’s system, pathologist Nathaniel Cary told the inquiry his team had to perform “one of the most dangerous autopsies undertaken in the western world”, with biochemical suits and filtered air. Cary added he knew of no other reported case of acute Polonium poisoning recorded anywhere else in the world.

As the hearing continued, the inquiry heard even more extraordinary claims about the suspects. A key witness testified that Kovtun, who allegedly lived as an asylum seeker in Hamburg in the early 2000s, had returned to the German port city days before flying on to London to meet with Litvinenko in 2006.

![Russian deputy parliament member Andrei Lugovoi [Associated Press]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/4e2abe815a71434b8ccbac220f39d10f_18.jpeg)

On arrival, he met with an old colleague from the days when Kovtun worked at an Italian restaurant. The witness claimed Kovtun spoke of Litvinenko as “a traitor with blood on his hands”, and asked if he knew a chef in London who could add poison he had acquired to the dissident’s food and drink.

Both Lugovoi and Kovtun denied the allegations. On Wednesday Lugovoi – now a deputy in Russia’s State Duma (lower house of parliament) and presenter of a documentary series on Russian TV called “Traitors” – gave an interview to the Ekho Moskvy (Echo of Moscow) radio station.

“This is an old story you are rehashing now,” Lugovoi said. “When the situation in Ukraine kicked off and the UK’s geographic interests likely began to change, they decided to dust off the mothballs and commence proceedings.”

On the blacklist

The Russian embassy in London did not respond to Al Jazeera’s repeated requests for comment.

Gulnaz Sharafutdinova, senior lecturer at Kings College Russian Institute, said the Litvinenko inquiry is not likely to change the frosty relations between Moscow and London.

“I don’t see a particular spillover from the Litvinenko affair in Russia. This is a symptom of the new state of UK-Russian relations, and it’s indicative of the polarisation processes that have been going on for over a year now. If anything, it won’t change the tone of animosity of how the West is painted in the Russian press, and the perception of how it is trying to corner Russia.”

American hedge fund manager Bill Browder knows all too well the experience of being on the end of the Russian justice system. As CEO of Hermitage Capital Management, once the biggest foreign investor in the country, he was blacklisted in 2006, his offices raided by police and a sizable amount of assets seized.

In 2013, Russian authorities charged Browder and his lawyer Serge Magnitsky with tax evasion, the conviction of the latter was served posthumously as Magnitsky had been jailed in 2009, tortured, and left to die an agonisingly painful death.

This caused the United States to pass the Magnitsky Act, levelling sanctions on key Russian officials suspected of involvement in the lawyer’s death.

Speaking from his offices in London, Browder told Al Jazeera: “One of the most shocking policy decisions was the statement made by the British Home Secretary in 2013. You have a terrorist incident leading to the death of a UK citizen using nuclear materials, and they wanted to quash the inquiry on the basis that it would hurt relations with Russia.

“Vladimir Putin is the most dangerous man in the world right now, and anyone who thinks he can be coaxed into good behaviour is missing the point.”

Follow Andrew Connelly on Twitter: @connellyandrew