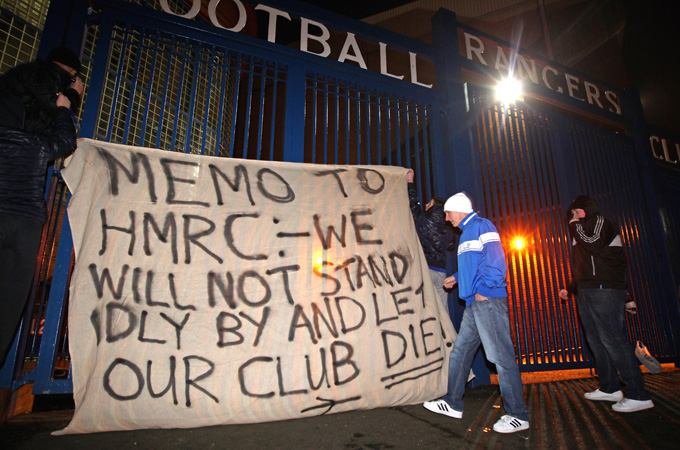

Rangers on the brink

The club is dealing with management problems and sectarian violence associated with the team.

|

| The problems at Rangers follow some of the most dramatic years in its history [GALLO/GETTY] |

The name “Rangers” is one of the biggest in British football.

And while the Glasgow club has a rich history and passionate supporters, it is now in a perilous situation.

On Tuesday February 13, the Scottish champions were placed in administration following a legal stand-off at the Court of Session in Edinburgh. Since then, every new revelation about their financial affairs seems to beg more serious questions.

Rangers owe £9 million ($14 million) in taxes, dating back to the takeover of the club by Craig Whyte in May 2011. The money was deducted from employees’ salaries, but never handed over to Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, Britain’s state tax agency.

Club officials are also awaiting the outcome of a separate tax case, regarding paying players via offshore accounts, that could leave the club facing a bill they can’t afford to pay – reportedly as large as £70 million ($110 million).

Adding to the fans concerns, insolvency firm Duff and Phelps say that they do not know the whereabouts of £24 million ($37 million) garnered through a deal with ticket agency Ticketus – which, the administrators say, did not go through the club’s accounts.

This money was reportedly paid into the bank account of a parent company, belonging to owner Craig Whyte.

The administrators have tried to allay fears that the club will cease to exist, but liquidation is a real possibility.

Rangers would not be the first football club to go bust, but they are by far the biggest. The Glasgow club has won 54 Scottish league titles – more national trophies than any other team on the planet.

The team’s supporters travel to games from all over Scotland, Northern Ireland and England. On match days, the average attendance is higher than successful English such as Liverpool, Tottenham and Chelsea.

History and identity

Supporting any football club is an intensely personal experience that draws on history and identity. Alasdair McKillop from the Rangers Supporters Trust told Al Jazeera that for some fans, “it is a bond between family members and across generations”.

The club’s downfall follows some of the most dramatic years in its history.

|

“The anger about how the club has been run in recent years is widespread and intense.“ – Alasdair McKillop, Rangers Supporters Trust |

In the 1980s, player-manager Graeme Souness brought some of the biggest names in the game to Ibrox. English international stars such as Terry Butcher, Ray Wilkins and Trevor Francis all took the road north.

They were tempted by high wages and the promise of European competition at a time when English clubs were banned from the continent because of hooliganism.

Rangers’ transformation continued with the arrival of businessman David Murray, who acquired the club for £6 million in November 1988. He famously boasted that “for every five pounds Celtic spend, we will spend ten”.

His claim that Rangers would always outspend their local rivals now looks very foolish. He turned out to be the sporting equivalent of former RBS boss Fred Goodwin, leading his team on a dizzy spending spree that ended in disaster.

“The anger about how the club has been run in recent years is widespread and intense,” McKillop told Al Jazeera.

“Sir David Murray is held chiefly responsible for the club’s current predicament and many supporters would like to see him being held to account, although it is difficult to see how this could be engineered.”

Rangers supporters care deeply about their history and many see their club as a focus for celebrating a sense of Britishness that is informed by close links with Ulster Unionism.

At its worst, this can have a dark underside, laced with religious bigotry and anti-Irish racism. For most of the 20th century, the club gave official sanction to such intolerance through its refusal to sign Catholic players.

This reflected a broader culture of discriminatory employment practices against Irish Catholic immigrants in Scotland. It could be difficult for Catholics to find work in occupations as diverse as the steel industry, banking and the police.

It was not until 1989 that Rangers made a decisive change, with the acquisition of the flame-haired Scotland international striker Maurice Johnston.

He had made his name as a prodigious goal scorer for Celtic and his transfer was a significant statement by Graeme Souness and David Murray that the old prejudices had no place in the modern game.

Unfortunately, not all of the club’s supporters got the message. Songs such as “Billy Boys”, which includes the lyric “up to our knees in Fenian blood”, continued to be sung at Ibrox until very recently.

In April 2011, UEFA fined Rangers $50,000 and banned its fans from the next away European game for sectarian songs sung in a match at PSV Eindhoven.

Sectarian violence

Nil by Mouth is Scotland’s only charity dedicated to challenging sectarianism. It was founded in 1999 by Glasgow teenager Cara Henderson in response to the murder of her schoolfriend Mark Scott.

|

“For too long the tail has been wagging the dog and the silent majority of supporters who support their team and have no truck with sectarianism need to find their voice.“ – Dave Scott, Nil by Mouth campaign director |

He was just 16 years old when he was stabbed in the neck walking home through a run-down area of the city’s east end, after a match between Celtic and Partick Thistle.

It became clear at the trial that his killer was motivated by religious prejudice.

In Scotland, it is difficult to imagine football without Glasgow’s Rangers-Celtic Old Firm rivalry, but Rangers’ demise could remove a significant focus for sectarianism.

“It’s certainly the case that Scotland would be better off without sectarianism and there is no escaping the fact that both clubs have real problems,” Nil by Mouth Campaign Director Dave Scott told Al Jazeera.

“A vocal section of their support still cling to outdated sectarian attitudes and insist on repeating old battles.

“For too long the tail has been wagging the dog and the silent majority of supporters who support their team and have no truck with sectarianism need to find their voice.”

During Saturday’s game against Inverness, Celtic supporters sang: “We’re having a party when Rangers die.”

The Scottish champions may be in the hands of the administrators, but most observers expect them to continue in some form.

“It is almost inconceivable that the a club of its stature with a massive support base will disappear into the ether,” observed McKillop.

At the root of fans’ anger is the belief that football clubs should not be run along the same lines as other businesses.

Rangers is a big part of many people’s lives, but the fans are unable to hold the club’s directors to account or ensure that it is run with openness and transparency.

Other European countries take it for granted that football clubs belong to their supporters.

Barcelona is the most famous co-operative in the world. The Catalan giants will never be subjected to a takeover by the likes of David Murray or Craig Whyte – because the fans themselves own the club.

Maybe they point the way off the field as well as on it.

Follow Andrew McFadyen on Twitter: @apmcfadyen