Security improves, with a cost for daily life

Hundreds of checkpoints and miles of concrete barriers snarl traffic but provide a tenuous security in Baghdad.

Many of Baghdad’s neighbourhoods are now sealed off, accessible only through checkpoints guarded by soldiers

Many of Baghdad’s neighbourhoods are now sealed off, accessible only through checkpoints guarded by soldiersBaghdad, Iraq – Four people killed and six wounded, three of them judges, when unknown gunmen attacked a minibus carrying justice ministry officials in Fallujah.

A police colonel in Mosul shot dead outside his house; two officials from the interior ministry in Baghdad assassinated by gunmen in the dead of night. And a suicide bombing near a police patrol in the capital’s Saadoun district, killing one officer and wounding five other people.

That is an incomplete accounting of the attacks over the last 48 hours in Iraq, and it is remarkable for how unremarkable it is: Violence here is still widespread, with hundreds of people killed each month, and it has become almost numbingly routine. When gunmen mortared Baghdad’s international airport on Sunday, the attack didn’t even merit a mention on Iraqi television.

Iraqi security officials, in interviews, tend to downplay the violence, portraying it as the last gasp of defeated militias and other armed groups.

“We indicated at a previous time, that… the more we approach the US pullout, the more we would witness escalation of terrorist operations,” said Maj. Gen. Qassim Atta, the spokesman for Iraqi security forces in Baghdad. “What is left of those terrorist groups are trying to prove their existence.”

Many Iraqis on the street, though, are less sanguine, and so are the US military officers who are leaving the country for good in the next two weeks.

“We really don’t know what’s going to happen,” acknowledged Lt. Gen. Frank Helmick, the deputy commander of US forces in Iraq, during a press conference last week.

A slowly improving picture

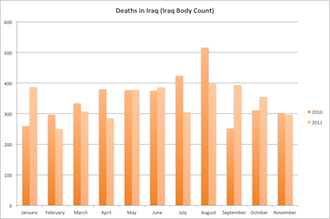

Despite the still-frequent attacks, violence in Iraq has actually ebbed rather than escalated over the last few months, though the degree of improvement depends on whose statistics you trust. 2,460 people were killed from January through November, a 30 per cent drop from the same period in 2010, according to official statistics from the Iraqi government.

But numbers from the independent Iraq Body Count suggest just a two per cent drop (click to enlarge)

But numbers from the independent Iraq Body Count suggest just a two per cent drop (click to enlarge)The independent Iraq Body Count has a grimmer tally: 3,741 fatalities in the first eleven months of 2011, just a 2 per cent decline from the previous year.

(The government does not release a detailed accounting of its data, so it is difficult to explain the differences between the two data sets. Critics have often accused the Iraqi government of downplaying violence to burnish its image.)

Both data sets show that violence has decline since the summer, despite a string of high-profile mass casualty attacks in November. That mirrors a trend from past years, when attacks tend to drop during the winter.

The situation is certainly much improved from 2005 and 2006, when thousands of civilians were slaughtered each month. That improved security has come at a cost, though: The massive army and police presence on the streets disrupts ordinary life.

Hundreds of checkpoints dot the roads, snarling traffic. Soldiers in armoured vehicles guard the entrances to markets and commercial streets. Many roads are simply sealed off, and access to individual neighbourhoods is controlled through one or two checkpoints.

Atta said the government is also pressing ahead with the “Baghdad Security Wall,” a plan to ring the entire Iraqi capital with barriers; the city would be accessible only through a small number of “gates.”

“After 2006 and 2007 it became stabilised, and until now the situation is good,” said Hameed Shaker, 61, a grocer in the Ghazaliya neighbourhood in western Baghdad. “[It] is getting back like it was before, because of the presence of the army. They are cooperating with us, they are respecting us.”

In a visit last week to a checkpoint in Ghazaliya, the Iraqi soldiers posted there seemed thorough, peering inside cars and pulling some out of the queue for a search – though the Iraqi army would not allow Al Jazeera to interview any of the soldiers.

The security forces are slowly winning Iraqis’ respect, though questions linger about the army’s readiness. Soldiers and police officers still rely on “bomb sniffers,” metal wands which are supposed to detect the presence of explosives. The Iraqi army spent tens of millions of dollars to buy the wands from a British company, ATSC Limited, even though the US military and independent studies have found them to be practically worthless, little more than divining rods. The head of the company was arrested last year on fraud charges.

Some soldiers have been accused of human rights abuses; others are simply green, the vast majority of the force having been recruited within the last five years.

“The scaling up at the ministry of interior has meant that they have hundreds of thousands of people serving in their police services… many recruited in a fairly limited period of years,” said a US embassy official here, describing that as a “daunting” challenge.

Fragile consensus

The situation is not entirely “like it was before” in Ghazaliya, of course: Two days after Al Jazeera visited, gunmen killed an Iraqi intelligence officer driving through the neighbourhood on the Abu Ghraib expressway. And a roadside bombing earlier this week, not far from the checkpoint, wounded six people, including two policemen.

Iraqi soldiers still rely on “bomb sniffer” devices which the US military has rejected as worthless

Iraqi soldiers still rely on “bomb sniffer” devices which the US military has rejected as worthlessSome of Iraq’s violence is still expressly sectarian, like a string of bombings last week which ripped through groups of pilgrims in Hilla and other cities as they commemorated Ashura, the Shia day of mourning.

Increasingly, though, the targets are members of the government and the security forces – not just senior officials, but lower-ranking police officers and soldiers as well. Assassins frequently used silenced weapons and “sticky bombs,” remotely-detonated explosives planted underneath cars, to target them.

Earlier this month, security forces even discovered a bomb hidden in a car belonging to Osama al-Nujaifi, the parliament speaker, while it was parked in the heavily-fortified “green zone,” supposedly the safest place in Baghdad.

Atta said security forces have increased security in the area, and indeed the drive inside the zone can now take upwards of an hour, with cars stopped at four to seven checkpoints. He said most of the ingredients for the bomb were gathered and assembled inside the green zone.

“The enemy tends to change its methods by using explosive materials which are locally produced,” Atta said. “Those items could not be discovered by the detecting devices, K-9 [bomb-sniffing dogs], even a manual search.”

In a sign of the sharp divisions here, Iraqi politicians couldn’t even agree on the intended target: Nouri al-Maliki, the prime minister, claimed that the bomber was actually trying to assassinate him, not Nujaifi.

“The biggest challenge for Iraq beyond 2011, in 2012, is to maintain and protect the political consensus which has led to the new regime,” said Hoshyar Zebari, the Iraqi foreign minister, in an interview last week. “That requires a great deal of responsibility by Iraqi leaders and politicians. And already, in the lead to the withdrawal… you’ve seen a number of signs that this consensus is showing strains.”