Youngest MPs reject Afghan ‘old guard’

Making use of grassroots campaigning, a new generation of candidates carve out a niche in parliament.

|

| Young Aghans want the same youth-led movements as those in the Middle East – but lack the security to make their voices heard in public [GALLO/GETTY] |

Baktash Siawash has had to hear one phrase more than any other during his career: “We won’t speak to him. He’s just a young boy.”

Siawash is 25 years old and the youngest member of the Afghan parliament – and as both a politician and a former journalist for Afghanistan’s most popular TV station, he has found many who are unwilling to accept him on account of his youthfulness.

“I may be young, but my intelligence is no less than [that of] anyone else,” he tells Al Jazeera.

Statistically, young people account for the clear majority of the Afghan population. However, an amalgamation of historical and cultural forces – 30 years of conflict, traditional Afghan family structures, massive illiteracy, and rampant corruption in the Afghan government – have left many of Siawash’s peers feeling politically disenfranchised. But Siawash knew that feeling silenced and being silent were two separate things.

He says Afghan youth want the same youth-led movements as those sweeping the Middle East, but most lack the security to make their voices heard in public.

Believing that he had a first-hand understanding of what the youth of Afghanistan wanted from their nation, in 2010, Siawash set out to add his name to the list of more than 2,500 others running for 249 seats in the Wolesi Jirga (lower house) of the Afghan parliament.

Family and finances

Before he could set out on his bid to change the political landscape of the Central Asian nation, Siawash would first have to address two matters familiar to all Afghans, young and old: family and finances.

Siawash argued late into the night with his father over the decision to run. “He was initially against me running because he said: ‘You need money and a name to run for government in Afghanistan.'”

Though his family remained hesitant about his political aspirations, “as a Muslim you have to ask for your parents’ blessing in all pursuits, so in the end that’s all I could ask my parents for – their prayers.”

Despite his family’s reservations, he stayed up until the next morning filling out the paperwork for his candidacy. With the family concerns at least temporarily assuaged, Siawash diverted his attention to the financial matters of candidacy: the 35,000 Afghanis ($750) needed to apply.

Though he had been working as a journalist since before entering university, Siawash says most of his earnings from Tolo TV went towards the clothes he wore while working his television job. “This put Siawash in a similar situation to other young, politically motivated candidates who didn’t have access to a lot of money,” Matthieu Aikins, a freelance journalist who covered last year’s parliamentary elections, told me.

“I didn’t even have a car to sell,” says Siawash. With options limited, he asked a friend in the wealthy Makroyan area of Kabul for the money. Fearing his friend would laugh at him, Siawash hid the reason he needed the money. “I was afraid he would have said: ‘You want to run for the parliament, but you’re asking me for money?'”

His campaign experienced initial success – gathering twice the required 1,000 signatures for his candidacy from an enthusiastic support base that “never asked where I was from or what language I spoke”, he said. But Siawash had entered “a hugely crowded field where hundreds of people are running for hundreds of thousands of votes over large geographic areas,” Aikins told Al Jazeera.

This labyrinthine nature of the fledgling Afghan democracy meant many of the younger candidates, such as 29-year-old Farida Tarana, a contestant on Afghan Star (a TV show along the lines of American Idol), had to “carve out their own particular niche”. But it was Siawash, says Aikins, who serves as one of the most successful examples of a younger candidate able to set himself apart from more than 2,000 in the electoral race.

As part of this niche, Siawash turned for support towards the increased numbers of youth taking active roles in the 2010 parliamentary elections. Aikins describes these youth supporters – ranging from 18 to 30 years old – as “a distinct group in Afghanistan” who came of age in a post-2001 environment, who enjoyed unprecedented access to education and interaction with foreign nationals through their involvement with foreign NGOs.

“They have different expectations, they are more inclined to change the status quo,” says Aikins of the new generation of politically engaged youth.

“Many youth candidates made use of door-to-door campaigning for the first time,” says Nadir Nadiry, chairman of the Free and Fair Election Foundation of Afghanistan.

Siawash says his youth supporters who had been working for NGOs and international aid organisations paid for many of his campaign materials. This came as a relief to Siawash because he had little money. In fact, Siawash says his supporters were so involved that “I would find my flyers in places I hadn’t even campaigned in, they would take my campaign materials, make copies and distribute it all without my ever knowing.”

Busy guaranteeing its existence

But growing from the youthful candidate who often had to ask for rides to campaign gatherings would prove to be much more testing. Siawash was about to enter a parliament that would become “very busy with guaranteeing its own existence”, says the Afghanistan Analyst Network’s Fabrizio Foschini.

Referring to Siawash and other young MPs, Nadiry told Al Jazeera: “They are bright and motivated, but they need to go through a learning process on what sorts of tools to use in pushing their agendas forward.”

Nadiry states that the youth vote “gravitated towards candidates who were presenting actual agendas and ideas,” as opposed to older politicians relying on traditional tropes of Afghan politics to bolster support.

Though Siawash says “my voice is not mine alone, it is of an entire generation”, Nadiry responds that, in the year since elections he hasn’t “heard anything specific from young MPs about engaging the youth in politics”.

Shah Reza Ghaznawi, a 33-year-old parliamentary intern, says that “very few of the MPs are interested in youth”. Politically, however, Siawash says what the youth want is “for all the political organs in Afghanistan to operate properly under the law”.

As an already recognisable face from his time as host of the Explore and Election 88 programmes on Tolo TV, Siawash “immediately stepped forward for an active role” in the parliament, even adding his name to the ballot for Speaker of the Lower House, said Foschini.

Foschini attributes Siawash’s outspokenness to his television background, an attitude that has not been without its criticisms. After equating the ruckus of the parliament to the behaviour of schoolchildren, Siawash says he heard a Kandahari MP levelling the familiar accusation that he was “a little boy trying to tell politicians how to behave”.

But Foschini sees the argument as evidence of Siawash impressing his presence on other MPs. “By the next day they were on such good terms that the Kandahari MP agreed to be Siawash’s representative in the counting of the votes,” says the analyst.

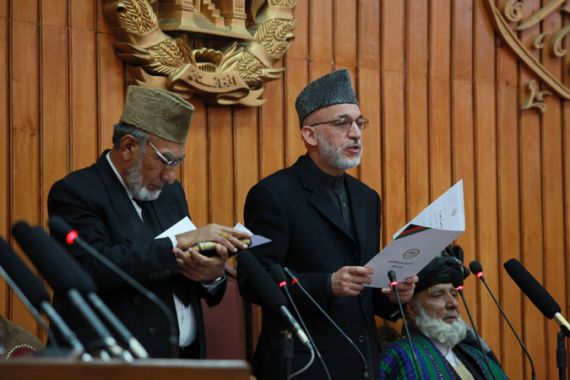

Perhaps also owing to his television background, Siawash engaged in fiery rhetoric about the Afghan political establishment. Days before speaking to Al Jazeera, Siawash publicly called for the impeachment of Afghan President Hamid Karzai, claiming that the president “stores millions of dollars from Iran in his office” and that he has yet to hold Pakistan accountable for “interfering in Afghan affairs”.

In an interview with Al Jazeera, Siawash said: “In Afghanistan, we don’t have a leader in the way Gandhi was a leader. We have four or five partisans with money.” Siawash added that he believed President Karzai is simply “a dictator”.

Reportedly ongoing electoral fraud and voter intimidation allegations have hampered much of the parliament’s activities, making the effectiveness of Siawash and other young MPs harder to gauge. However, Nadiry says, “all MPs, young and old, must realise that you cannot do things alone. You have to build coalitions,” something that Siawash’s claims could make very difficult.

Siawash doesn’t have to look too far for an example of outspokenness costing a youthful, idealistic MP political credibility. At 27 years old, Malalai Joya was the youngest member of the previous Wolesi Jirga, elected in 2005. However, by May 2007, Joya’s claims that warlords, drug lords, and war criminals had taken root in the parliament proved to be too much. Dubbed “the bravest woman in Afghanistan”, she was dismissed from the Wolesi Jirga.

Nadiry says that Joya’s inability to rally support around her statements about human rights conditions in Afghanistan proved to be problematic. According to Nadiry, “she made it harder for the people who were risking their lives to bring change to Afghanistan”.

Fresh-faced poses

Though Nadiry says 65 per cent of the 7,500 electoral monitors for the nation’s largest non-governmental election monitor, the Free and Fair Election Foundation of Afghanistan, were all youth, Aikins warns of too quickly accepting the “notion that being a youth candidate is the equivalent to being an independent reformist”.

Aikins says Siawash and other young MPs must work to maintain the youthful support that first got them into office as “there are no real natural constituencies in Afghan politics”.

Aikins refers to the manipulation of female candidate quotas as evidence of the fact that not all young political hopefuls are “youthful reformists” like Siawash. Aikins says “big families” put forward younger women that would “adopt a fresh-faced pose but often supported the same warlord politics” that have become standard in the Afghan political scene.

Farkhunda Zahra Naderi, the 29-year-old daughter of Ismaili spiritual leader Sayed Mansoor Naderi, was quoted by the AFP in 2010 saying that her parliamentary platform “is on women’s rights and human rights” – but her family’s economic and political connections have left some wondering if Naderi’s successful bid for one of the nine female parliamentary seats in Kabul was an example of what Aikins calls “back-room political games … that don’t have [anything] to do with party politics or representing the public in any way”.

Aikins says these deals, which have been going on in Afghanistan for decades, have left their mark on many young people in Afghanistan. Youth political engagement may have increased in the 2010 parliamentary elections, but Aikins says these political games have also “led many young people to feel that there is no real stage for people trying to do the right thing in Afghanistan.”

Though Siawash maintains that “everyone who voted for me is of a new generation, who want to bring a change to Afghanistan”, voter turnout for the parliamentary elections was less than half of 2009’s much-contested presidential elections.

For Aikins, the fact that voter turnout in Kabul – where Naderi and Siawash both won seats – was low, despite greater security than much of the rest of the country, can be seen as proof that much of the youth may have felt “their votes don’t matter and their voices won’t be heard”.

Politics as usual

No matter the actual levels of youth political engagement in Afghanistan, Siawash maintains that he is a voice for the youth of the nation. Noting that many of the problems plaguing the youth of Afghanistan today have to do with joblessness, Siawash says it is increasingly important for politicians to engage with disgruntled young Afghans.

“While looking for food and opportunities, many have fallen into the hands of the enemies of Afghanistan,” says Siawash.

To Nadiry, for younger MPs like Siawash and Farkhunda Zahra Naderi to win the continued support of the youth “they have to work to help the parliament move from daily politics of rhetoric surrounding current events and towards the substantive drafting of legislation”.

Siawash sees the previous parliament’s inability to address the nation’s most pressing youth issues as an example of “hidebound bureaucratic inertia” in the Afghan political system. “They spent more time trying to figure out which term [in Persian] to use for ‘university'” than they spent addressing actual youth issues,” Siawash told Al Jazeera.

Despite the challenges facing them, Nadiry says younger MPs such as Siawash “do present a new face” and a much-needed “move from the old faces of politics as usual in Afghanistan”. Parliamentary intern Toorialai Toorman, speaking from the offices of the USAID-funded program a day after Siawash again called for the impeachment of President Karzai and an argument between two female MPs turned violent, says he is hopeful for a parliament that is “becoming more and more the people’s parliament”.

For Siawash, who proudly declares that he neither has a bodyguard nor lives in a compound like many of the nation’s political elites, his role is simple: “I am of the people. If they want me I will stay, and when they don’t I will leave.”