A scramble for the Arctic

With one fifth of the world’s oil and gas at stake, countries are struggling to control the once-frozen arctic.

|

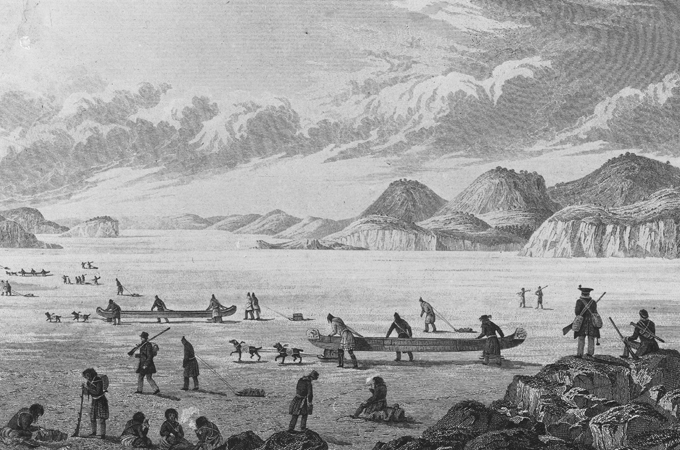

| Foreign powers fighting for control of the Arctic is nothing new, but global warming, the search for resources and the end of the Cold War have led to a new battle for northern dominance [GALLO/GETTY] |

From her office in the frozen north, Delice Calcote has watched big powers vie for control over the Arctic with little concern for its original inhabitants.

“This is our land,” said Calcote, a liaison with the Alaska Inter-Tribal Council, an advocacy group representing the region’s indigenous peoples. “We aren’t happy with everyone trying to claim it.”

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRainfall set to help crews battling wildfire near Canada’s Fort McMurray

The Alabama town living and dying in the shadow of chemical plants

How India is racing against time to save the endangered red panda

But as the planet warms, as northern sea lanes become accessible to shippers, as companies hungrily eye vast petroleum and mineral deposits below its melting ice, a quiet, almost polite, scramble for control is transpiring in the Arctic.

“Countries are setting the chess pieces on the board. There are tremendous resources at stake,” said Rob Huebert, director of the Centre for Military and Strategic Studies at the University of Calgary.

The frozen zone could hold 22 per cent of the world’s undiscovered conventional oil and natural gas resources, according to the US energy information administration.

Competing claims

Canada, the US, Russia, Norway and Denmark have competing claims to the Arctic, a region about the size of Africa, comprising some six per cent of the Earth’s surface.

The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is supposed to govern resource claims in the region.

“At this point, everyone is following the rules and say they want cooperation; behind the scenes developments are happening that suggest it may not be so cooperative,” Huebert said.

Under maritime law, countries can assert sovereignty up to 200 miles from their coast line. Article 76 of the UN convention allows states to extend control if they can prove their continental shelves – underwater geological formations – extend further than 200 miles.

Presently, the Lomonosov ridge, a 1,240-mile underwater mountain range, is testing the strength of the UN convention as Canada, Russia and Denmark all claim the potentially resource-rich region.

“Russia recently submitted a claim [but] the UN didn’t buy it [on scientific grounds],” said Gilles Rhéaume, a public policy analyst with the Conference Board of Canada, who recently authored a report on Arctic sovereignty. “Will the legal means be used to determine claims? We don’t know.”

A panel of elected geology experts rule on claims under the UN convention. They are mandated to make decisions based solely on scientific merit.

New colonialism

But polite conventions did not stop Russia from planting a flag more than 4,000 metres below sea level under the North Pole in 2007, in a flash-back to past imagery of colonial control.

“This isn’t the 15th century. You can’t go around the world and just plant flags and say ‘We’re claiming this territory’,” Peter MacKay, Canada’s foreign minister, said at the time.

But Canada, which prides itself on being the “great white north,” is also seen as an aggressor by many analysts. The country plans to build at least five navy patrol boats to guard potential shipping lanes in the Northwest Passage, along with new Arctic military bases and a deep water port on Baffin Island.

“Russia and Canada are the only two Arctic states who have ramped up the rhetoric on the military front,” said Wilfrid Greaves, a researcher at the University of Toronto.

Much of Russia’s military capacity, especially naval power, rusted away with the collapse of the Soviet Union, while Canada – protected by the US defence umbrella – lacks powerful military hardware.

Like small dogs with more bark than bite, or the impotent Hemmingway character sleeping beside a rifle, Canada and Russia are likely upping the rhetoric due to an inability to seriously project hard power.

Domestic politics also loom large, as leaders posture to look strong on sovereignty issues, pledging to defend national interests from hostile outsiders.

“The US, despite its military power, doesn’t rattle swords in the same way,” Greaves said.

The Norwegians are talking the most cooperatively, said Huebert, the University of Calgary professor, but “they are arming very assertively” recently buying at least five combat frigates with advanced AEGIS spying and combat capabilities. “The Danes are rearming too,” he said.

Indigenous concerns

As big powers assert claims, wrangle over the geology of their respective continental shelves and stock up their militaries, indigenous peoples in the Arctic have faced a colonial scramble since Europeans first arrived.

“Statehood happened without our consent,” says Delice Calcote, the indigenous activist from Alaska. Russia first colonised the region, and then sold it to the US in 1867 for $7.2m.

“It is our land and our water. They [the US] don’t own it, it is ours,” Calcote said, echoing the view of some indigenous peoples from Greenland, through Canada, Norway, and Siberia.

While Sarah Palin, Alaska’s former governor and current right-wing political star, won standing ovations for her chants of “drill baby drill”, Calcote said her people rely on oil donated from Venezuela, despite the teritories’s vast petroleum wealth.

“They [Venezuela’s leftist government] know about the horrible conditions in the villages: no running water, no sewers and the decline in our traditional food sources,” Calcote said.

The harsh divide between official state policy, and the conditions of people actually living in the Arctic, is not confined to the US.

“The Canadian Arctic has some of the highest levels of poverty and substance abuse in the country,” said Greaves, who participated in a major conference linking northern communities with southern researchers and academics.

“In [Inuvik] one of the larger communities in the Arctic, none of the indigenous people I met exhibited any concern with the military approach to the Arctic.

“People were interested in unemployment, a lack of resources [and] climate change … in Greenland, the situation is probably similar, [Arctic residents] don’t feel they have any voice in the south, with respect to climate change and policy.”

Melting ice

Global warming, partially caused by burning fossil fuels, is largely responsible for the new scramble for the northern region, as once impenetrable ice blocks melt at an alarming rate.

“It’s a terrible irony that melting ice caps are allowing companies and even governments to open up the possibilities of new oil developments,” said Ben Ayliffe, a senior climate campaigner with Green Peace in the UK.

Cairn Energy, a corporation based in Scotland, recently began drilling oil wells in waters off Greenland’s coast. “There are reasonable [environmental] concerns given the extreme nature of drilling in the Arctic,” said Ayliffe who’s organisation has tried to physically block drilling.

“If something went wrong up there, the companies do not have the money to cover the cost of the spill,” he said, adding that Cairn refuses to publish a spill response plan.

Climate change concerns notwithstanding, a Gulf of Mexico-type oil spill in the Arctic would wreak havoc on what Ayliffee calls “an iconic area of the natural world.”

Cold Warning

Global warming and the hunt for resources are not the only trends leading to the latest scramble. “During the Cold War, the Arctic was a buffer zone, insulating North America from the Soviets and vice versa,” said Greaves. “It served a valuable function and no one was willing to tamper with it too much.”

Like conflicts in the Balkans or the Democratic Republic of Congo, kept in check by Cold War politics, the end of the bi-polar world order transformed relations in the Arctic. That, onto itself, is not a recipe for a fight.

“Conflicts exist, but there are so many mechanisms designed to deal with it that the likelihood for physical conflict is very remote,” said Gunhild Hoogensen, a professor specialising in the Arctic at the University of Tromso in Norway.

Perhaps new frigates and bases are merely political theatre, the war dance of international relations where countries can flex – before negotiating – without spilling blood.

But with more than one fifth of the planet’s energy reserves potentially on the line, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

The invasion of Iraq was “largely about oil,” according to Alan Greenspan, the former chairman of the US federal reserve. And unenforceable UN conventions on conflict settlement might be insufficient to prevent the Arctic scramble from turning violent.

“We are truly in a period of transition,” Huebert said. “I could see us heading for either cooperation or conflict.”

You can follow Chris Arsenault on Twitter: @AJEchris