Lebanon’s men of letters

The Christian scholars who led the Arabic literary revival of the 19th century.

|

Nasif al-Yaziji

Like several of the principle players of the Arab Awakening (Nahda), Nasif al-Yaziji migrated from a Mount Lebanon ravaged by discord and revolt, to Beirut at a time when the city was undergoing rapid development and establishing itself as a centre of academia and journalism.

A Greek Catholic, he began his career as a private secretary (mudabbir) – a common way for Christians to attain social mobility under the restrictive iqta’ system by which Mount Lebanon, which he described as “a country of tribes”, was governed.

First employed by Prince Haydar al-Shihabi, he went on to work for Bashir Shihab II (1788-1840), whose brutal repression of his opponents earned him the title the “Red Emir”.

When al-Yaziji moved to Beirut in 1840 he became an Arabic tutor and it was in this role that he came into contact with American and British Protestant missionaries. He would help fulfil one of the greatest ambitions of the missionaries – the translation of the Bible into Arabic – when he corrected a translation that Eli Smith (1802-52), an American missionary, and Butros al-Bustani (1819-83) started in 1847.

After this he taught at the Syrian Protestant College (later renamed the American University of Beirut) and wrote on poetry, rhetoric, grammar and philosophy. It was for his attempts to emulate the style of classical Arab writers, thereby rediscovering the literary heritage of the Arabs, that he is best known.

Among his works are a treatise on the muqata ‘ji system. Used by the Ottomans to govern the emirate of Mount Lebanon, this involved tax-farming or iqta’ rights being given to leading local families. These families enjoyed a degree of autonomy in the running of their region, controlled the land, collected taxes and benefitted from tax exemptions and benefits in exchange for providing the central authorities in Istanbul with revenue and armed men.

With al-Bustani and Mikha’il Mashaqqa, al-Yaziji formed the Syrian Association for the Sciences and Arts – the Arab world’s first literary society – in 1847. The circle tackled and published its deliberations on themes such as women’s rights, history and their fight against superstition.

It was dissolved in 1852 but its inner circle went on to establish the Syrian Scientific Association a few years later. This became a much larger, multi-sectarian society of intellectuals who pushed for Arab independence from the Ottomans.

Butros al-Bustani

A Lebanese Maronite Christian, al-Bustani is regarded among scholars of modern Arab history as a pioneering proponent of pan-Arabism.

Born in 1819, al-Bustani came into a world beset by the rise of Arab nationalism against the French invasion of Egypt and Ottoman occupation of Lebanon and Syria at the turn of the century.

His study of Arabic poetry, literature, and several Semitic languages led him to translate the Bible into Arabic and also work on the first Arabic encyclopaedia in 1881.

It was during this time that he came to realise that a pan-Arab cultural reawakening was the only way the Arabs could overcome the yoke of Ottoman dominance.

To this end, he founded the first co-educational Arab school in Beirut, countering illiteracy that was common among the Arabs living under Ottoman rule.

Half a century before TE Lawrence helped the Arab tribes to fight the Ottoman Turks, it was al-Bustani who called for an uprising against Constantinople.

He would be the first in a long line of Christian pan-Arabists who contributed to an Arab nationalistic identity.

Ibrahim al-Yaziji

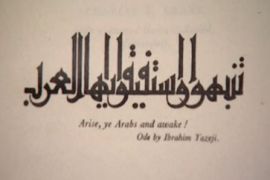

It was at a meeting of the Syrian Scientific Association in 1878 that Nasif al-Yaziji’s son, Ibrahim (1847-1906), recited an ode that would become a slogan for Arab nationalism, the cultural roots of which were beginning to take hold.

It was never printed but Arise, ye Arabs and awake, which praised Arabs and called for their unity, was passed along orally and gained widespread fame.

Ibrahim al-Yaziji taught at the Ecole Patriarchale and the National School in Beirut. A linguist, he called for and contributed to the revival of the Arabic language.

His interests included poetry, with which he began his literary career, art and astronomy. He was also considered to be one of the best calligraphers of his generation.

At the Paris exposition of 1878, his Arabic translation of the Jesuit Bible won a gold medal.

One of his most significant innovations was the creation of a greatly simplified Arab font. By reducing Arabic character forms from 300 to 60 he simplified the symbols so that they more closely resembled Latin characters. It was a process that contributed to the creation of the Arabic typewriter.

Ibrahim fled to Egypt to avoid Ottoman repression and died in exile.