China’s mentally ill: To treat or ‘re-educate’?

School attacks highlight complex relationship between mental illness and dissidence in China.

|

| About 173 million Chinese have some form of mental disorder [GALLO/GETTY] |

A recent spate of attacks targeting children has shone a spotlight on the state of mental health care in China and its growing social implications.

The first of the attacks took place on March 23, when a former doctor stabbed eight children in a nursery in the southeastern Fujian province.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIn India’s richest state, exam scams kill escape from farm crisis

Displaced 12-year-old boy becomes Gaza’s youngest medic

Why are so many young Americans suffering from mental distress?

The 41-year-old reportedly said that he had “intentionally” killed the children because he felt like a failure.

“I chose them because they were weak and vulnerable. I killed them to get attention,” Chinese media quoted him as saying.

The attack generated global media attention and a flurry of similar incidents followed.

At a time when the Chinese government hoped its Expo 2010 spectacular would garner column inches, it was instead forced to answer questions about a much less savoury side of the country’s rapid development.

“Apart from tight safety measures, we need to pay attention to addressing the root causes of these problems … That includes dealing with social conflicts and dispute resolution at the grassroots level,” Wen Jiabao, the Chinese premier, said in a televised interview.

Social inequality

|

| Tight security measures have been introduced to stop attacks on schools [Reuters] |

Some see such attacks as an extremely violent expression of deep-seated social ills – such as poor human rights, local authority corruption and land evictions – which have either been exacerbated by China’s sprint towards economic development or simply overlooked in the process.

“These incidents have deep social and psychological root causes,” Lin Chun, a scientist at the Psychological Institute of Beijing’s Academy of Science, says.

“In these days the social differences are acute. Some people have been put into a corner.”

With few societal protection mechanisms in place, Lin says, those who feel backed into a corner “don’t see any hope”.

And with rapid progression comes inequality of opportunity, Lin adds.

“One can take an opportunity, but another one can not – eventually he might fall into extremes, depending on personality and character.”

High-risk phase

As more and more Chinese witness others attaining the rewards of social and economic development, without benefitting from it themselves, some experts suggest that Chinese society is entering a high-risk phase.

“There seems to be an increase in disgruntlement, many people don’t believe in the legal system and are so often pushed to the limit,” says Yvonne Gerig, a psychologist who co-founded a project for mentally ill people in Beijing and also ran a nursery in the city for a number of years.

Gerig says that in a country where “bribes and corruption is so widespread it is not surprising that people take the law into their own hands”.

What is more shocking, she says, is that they should choose to target children.

“Maybe [it] is because children are so valued here [with] every family being able to have just one. So you go after what is most precious.”

History of discontent

|

| The government fears that millions of migrant workers could cause social unrest [AFP] |

China has a long history of violent reactions to social and political discontent.

Stan Rosen, a professor of political science at the University of Southern California who leads the university’s East Asian Studies Center, says that the violence of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution can, in part, be attributed to an outpouring of grief from a society that had long suffered the hardships of famine, impoverishment and oppression.

The Cultural Revolution offered an opportunity for ordinary Chinese to unleash the rage that such suffering had nurtured.

Martin K. Whyte, a sociologist at Harvard University and the author of the book Myth of the Social Volcano, does not see much dissimilarity with modern-day China.

He says that a caldron of discontent continues to bubble, with many Chinese feeling that they have no steam valve while the government keeps the lid firmly in place.

But Whyte does not agree that the attacks should be seen as a product of discontent over the rising inequality unleashed by market reforms.

A national survey Whyte conducted in 2004 found that most Chinese actually feel optimistic about their opportunities to get ahead.

Abuses of power

But, he cautions, this does not mean they are happy about everything.

“There is a lot of anecdotal evidence that many Chinese feel very angry about their lack of influence and control over the people who make decisions affecting them – in other words, strong feelings of procedural injustice.”

Whyte argues that while Chinese are told that their society is becoming increasingly “harmonious” and is guided by predictable laws, the reality feels very different.

Many regularly encounter bureaucratic obstacles and abuses of power that prevent them from obtaining fair treatment.

“I think it is these kinds of abuses people suffer from the powerful people who control decisions that affect their lives, people who cannot be readily influenced by persuasion or petition, not to mention democratic procedures, that infuriate them,” he says.

“And perhaps mentally unstable individuals, when they feel subjected to a relentless

series of abuses of this kind, decide that the most powerful way they can express their fury and frustration is to attack the most vulnerable members of the society, school children.”

He argues, however, that far from being a product of reform and growing inequality, “these power inequalities and procedural injustice issues … are rooted in the surviving Leninist control structures and impulses that still guide the operations of the CCP [Chinese Communist Party]”.

Losing balance

|

| Societal changes have contributed to increased levels of stress and mental illness [GETTY] |

With its control structures and economic reforms, China has managed what no other nation has done before: to pull millions out of poverty.

But what has been the human cost of economic development and rapid social change?

Despite rising living standards, Chinese face problems unknown 30 years ago.

“The faster society develops, the faster people’s lives become, and the more stressed they get.

“Many people feel they are losing their balance, and balance matters a lot to Chinese,” says Che Hongsheng, the dean of the psychology faculty of Beijing Normal University.

Suddenly confronted by increased divorce rates, higher costs for medical care, reduced job security, weaker communal relations, reduced social support networks and widening social and economic gaps, Chinese are experiencing rising levels of stress and mental illness.

China has one of the highest suicide rates in the world. With 250,000 to 300,000 suicides a year, China accounts for about one quarter of all suicides globally.

Michael Phillips, a Shanghai-based psychiatrist who serves as the executive director of the World Health Organization’s Collaborating Center for Research and Training in Suicide Prevention, conducted a study last year which found that 173 million Chinese – or 17 per cent of the population – had suffered from some sort of mental problem and that 91 per cent had never been treated.

Schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease and depression are the most common mental illnesses encountered.

Cost of treatment

With mental illness being the most expensive type of illness to treat – medical fees exceed even those for treating tumors and cardiovascular disease – many mentally ill people have only limited access to treatment.

Accessing treatment can be particularly difficult in rural areas where, according to Phillips, many still “don’t know anything about mental illness”.

And in a culture where mental illness is believed to reflect badly on the entire family, social stigma can stop people from seeking treatment.

“The mentally ill are still not being treated well. Mental illness is a stigma but this applies not only to China,” Gerig says.

“Unlike other countries, however, there is no support for the families and relatives. Often they have no one they can turn to so it is easier for them to have [the mentally ill person] locked up [rather than] having to deal with neighbours.”

Rehabilitation and integration

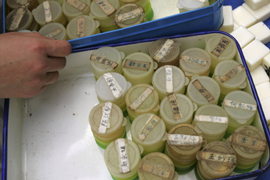

|

| Medication is favoured over other forms of treatment for mental illness [GALLO/GETTY] |

Psychiatry is historically a very underdeveloped profession in China.

Traditional Chinese theories of medicine do not consider mental disorders separately from physical disorders, and their origins are thought to be due to an imbalance in the internal organs.

Phillips says that just 20 years ago, his colleagues had to hide their work from their neighbours who feared that mental illness was contagious and could be passed on from psychiatrists.

China has about 20,000 certified psychologists, which is just 10 per cent of what other developed nations have proportionate to their populations.

Psychiatric treatment in China is largely provided through inpatient care and typically involves medication because talk therapy, popular in the US and Europe, is virtually non-existent in China.

The country is in dire need of more rehabilitation centres for people with mental health problems so that less severe cases can be reintegrated into the community.

“There needs to be reform and a stronger commitment to re-socialise people from locked facilities back into society,” Gerig says.

“There are no assisted living projects and occupational therapy is often not available, leaving patients with only medical intervention.”

Gerig fears that increasing pressures to achieve academically, teamed with a failure to employ school and university counselors, could result in greater levels of depression and mental illness among young people.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if we see more violent attacks in universities and high schools,” she says, adding that it would help if the general public was educated to recognise the early signs of a break down.

Counterrevolutionary

The Chinese government last year announced a plan to spend more than $100bn to create a system that would ensure basic health care for all by 2020. But experts estimate that only five to 10 per cent of that will be used for mental health care.

But Phillips is optimistic: “At the central level, there’s an increasing awareness of the importance of mental illness and I think these recent events will magnify this.”

There has long been a complex relationship between the government, political discontent, psychiatry and mental illness in China.

During the Mao era – when the emphasis was on subordinating the individual self to the collective – psychology was deemed counterrevolutionary and condemned as decadent bourgeois indulgence.

Most psychiatric facilities were closed down during the Cultural Revolution and those that remained open were forced to use political re-education – as mental illness was considered to be a result of holding the ‘wrong’ political opinions – as the primary basis of treatment.

Today, psychiatry is still being called on to ‘re-educate’ dissidents and with the absence of any proper legal procedure to prove mental illness, many who have fought against perceived injustice, have been declared mentally ill and institutionalised.

Qin is a former officer in the People’s Liberation Army who has been involuntarily hospitalised six times after petitioning against local authority corruption.

“The first time the diagnosis was acute stress disorder. The second time was paranoid schizophrenia. The third time, just like all the other petitioners, doctors diagnosed me with paranoid psychosis,” Qin explains.

Experts say that the attacks have at least helped to focus attention on the links between social problems and mental illness in China, as well as highlighting the devastating consequences of ignoring mental illness.

“There might be a minority of people with mental health care issues being violent but it is very difficult to draw a line,” Gerig says.

“How many people are mentally unstable in the West for a while only to be stable again? We don’t hear of similar attacks in other countries and there are people with mental health problems everywhere.”