Germany: Escaping the East by any means

Many East Germans felt trapped after the wall was constructed and tried to escape. A look at 10 dramatic escapes.

For some people living behind the Iron Curtain, the wish for freedom became so strong that they were willing to risk their lives to cross the heavily guarded border between East and West Germany.

| Special report |

|

The system used by the German Democratic Republic (GDR) to keep its residents from escaping became more and more sophisticated over the years, but so did the escape attempts.

During the 40 years of the GDR regime about three million of the country’s 17 million citizens left, around 75,000 each year; most of them without permission.

Hundreds were killed, but many others managed to make it to the West using ingenious and spectacular methods.

| Jumping the wire – a symbol of the Cold War |

When 18-year-old border guard Conrad Schumann jumped the barbed wire fence he was guarding he became the first defector from East Germany and a symbol of the Cold War.

The date was August 15, 1961, and the wall – which was then only a barbed wire fence – had been under construction for just three days.

As people on the West side of the street shouted “come over here,” Schumann jumped the barbed wire and was driven away by a waiting West Berlin police car.

“Many people were standing around, and that was good, because they distracted my colleagues,” Schumann said.

|

| Schumann jumped the barbed wire while the wall to divide Germany was under construction |

“I was able to swap my loaded sub-machine-gun for an empty one before I jumped. The jump was not so difficult then.

“After that the gun fell noisily on the ground; with a full magazine it probably would have gone off.”

Peter Leibing, a West German journalist, captured the leap to freedom and Schumann became a hero of the free world.

In his homeland, however, he was considered a despicable traitor.

Schumann was the first soldier from the National Peoples Army to escape, but it is estimated that 2,700 East German soldiers and policemen followed his example.

Eventually, he moved to Bavaria where he married and worked at Audi’s assembly line for nearly 30 years.

After his escape, he was interrogated by the Western authorities, but the Stasi, the East German secret police, wanted the Cold War icon back for their own purposes.

Schumann’s family wrote him letters asking him to return and promising that everything would be fine, but the letters were dictated by the Stasi.

When the wall fell and Germany was reunited, Schumann returned to Saxony to visit his family. But the homecoming was not what he had expected.

Many people were kind to him, but “there are still some people who refuse to speak to me,” he said.

‘The traitor’ remained a traitor to many, even if the GDR had disappeared.

He suffered from depression and on June, 20, 1998, his wife found him hanging from a tree in a nearby woods.

| Tunnel 57 |

|

| Some East Germans tried to break through the border, but were foced to stop [GALLO/GETTY] |

During the 1960s, many people tried to escape through tunnels, but these were often discovered.

In 1964, 30 students from West Berlin, led by the 25-year-old Wolfgang Fuchs who organised escapes for East Germans, dug one of the most spectacular tunnels.

The digging took several months and the tunnel which ran 12 metres beneath the Berlin Wall between Bernauer Street on the West and Strelitzer Street on the East, eventually measured 145 metres in length and 90 centimetres in height.

When the tunnel was discovered by border guards 42 hours after its completion, 57 men, women and children had already managed to escape to the West. But many more were still awaiting their turn when the GDR soldiers showed up.

In the fight that followed between the students and soldiers, soldier Egon Schultz was killed when a fellow soldier accidentally shot him.

The GDR claimed he was killed by West German agents and used his death as part of a propaganda campaign against escape attempts and West Germany.

| A home-made hot air balloon |

On September 16, 1979, two men, two women and their four children climbed out of a basket. They had been up in the air for 28 minutes.

Balloon sports were forbidden in the GDR, so they had made their own hot air balloon from bedsheets.

When, during their flight, a fire burned a whole in their makeshift balloon and they started to run out of gas, they sang songs to distract their children.

But, when they finally landed, they were unsure whether they had made it to the West or whether they were still in the East. For them the West meant freedom and the East imprisonment.

Peter Strelzyk says the women and children stayed hiding while the men went to see what country they were in.

They saw a policeman who confirmed that they had made it to the West.

That was their second attempt at escape. Their first had failed when their balloon landed just short of the border. Undetected they went back home to plan their next attempt.

“It was no longer possible for us to lie to our children and put up with the political conditions in East Germany,” Peter said.

| Escape via Afghanistan |

In 1984, in the mountains of Soviet-occupied Afghanistan, a woman fled from East Germany. For years, Kerstin Beck had carried the dream, and then the plan, of escaping the GDR.

As a 24-year-old student at East Berlin’s Humboldt University, she traveled to Soviet-occupied Afghanistan for intensive language training.

|

| Around 5,000 people managed to escape the GDR after Germany’s division [GALLO/GETTY] |

But from the day she arrived in Kabul six months before her eventual escape, she knew she would not return to East Germany.

“I couldn’t live the way I wanted; I couldn’t study what I wanted. I only knew one corner of the world, but I wanted to see all of it,” she said.

Just before she was due to return to the GDR, Beck met a Mujaheddin who took her to his mother’s house.

The women of the house asked her why she would want to go to Pakistan but were supportive when she explained that the GDR was a Communist state and she did not want to return there.

Early the next morning, on the day she was due to return to the GDR, some Mujahidden gave Beck the burqa that would be her disguise for the next few days and they set off on their journey.

At the checkpoints they crossed, Beck pretended to be the men’s cousin from Tajikistan.

Just a couple of hours after she started her journey, two fellow students told the East German embassy in Kabul that Beck was missing. Checkpoints were set up across the country and an aeroplane heading for India was held so that the security forces could check the passengers.

After the Mujaheddin had escorted her through the last army checkpoint and deep into their territory, they handed her over to four armed men who would accompany her to the border.

But four days later as the border was in sight, she was stopped by some armed men. The men accompanying Beck told her: “They found out that you are a Western woman – you are wearing the burqa, but the way you are walking is very different to an Afghan woman.”

Beck eventually crossed the border into Pakistan, but once there she was held at the Mujaheddin’s headquarters for nearly two weeks as the leaders of rival groups fought over her. Some wanted more money, one was convinced that she was a Soviet KGB spy and another wanted to marry her.

A member of an influential exiled Afghan family finally took her to live with them in Peshawar.

On April 14, 1984, one month after she started her journey from Kabul, Beck got on an aeroplane to Frankfurt in West Germany.

| Surfing to Denmark |

Dirk Deckert and Karsten Kluender dreamt of traveling, surfing, sailing and freedom.

“I wanted to live in a country where I could do what I wanted, I didn’t mind risking my life for freedom,” Kluender said.

The pair lived near the sea and decided to attempt an escape by surfing to Denmark.

Although there were some patrols along the coast and patrol ships in the sea, it appeared less dangerous than other escape routes.

Early one morning in November 1986, they approached the sea with their surfboards. They crossed the border without being seen and got into water. But shortly after setting off, Deckert damaged his wetsuit.

He knew it would be suicidal to continue in the freezing water without the protection of his suit so he headed back to shore to fix it and try again another day.

Meanwhile, Kluender, unaware of what had happened to his friend, was on his way. A few hours later, exhausted and worried that he had sailed off track, he spotted the Danish coast.

Safely in Denmark, Kluender worried that his friend had been caught.

But, the next day, with his wetsuit fixed, Deckert set out again. After six hours of surfing he saw a Danish fishing boat.

The boat was out looking for him and those on board already knew his name. That was how he learnt that Kluender had made it safely to Denmark the day before.

Deckert said: “If I had known that the wall would fall three years later, I would have stayed. Definitely.”

| Floating to freedom |

|

| Three West Germans used a hollow metal drum to help their girlfriends escape [GALLO/GETTY] |

Ingo Bethke’s parents worked in the GDR’s ministry of interior and were supportive of the ruling regime, but he was different; he wanted to see the world.

On May 22, 1975, just before midnight two border guards were telling jokes when 21-year-old Ingo approached the River Elbe with a blow-up mattress under his arm.

He knew that part of the border because he had had to serve there as a soldier before.

About 500 metres from the Elbe, he had cut a small whole in the border fence. He passed the minefield by using a wooden block to check the ground in front of him. If nothing exploded, he moved forward.

When he reached the river he saw a spotlight and police boats but there was fog so they did not spot him.

He blew up his mattress, climbed into the water and, 30 minutes later, he reached Lower Saxony – the West.

| A high-wire ride to freedom |

Holger Bethke, Ingo’s younger brother, and an electrician in East Germany escaped the GDR on March 31, 1983, using a steel cable and wooden pulleys.

There was a lot of planning involved. They had the rollers made from solid blocks of benchwood and communicated with Ingo by letters with fake return addresses, cryptic telephone calls and using other relatives as intermediaries.

They monitored the wall to scout for the right site, checked the chimney, made sketches, checked whether the skylight windows were large enough to fit through.

|

| Bethke was lucky that the guards in the watch towers didn’t spot him[GALLO/GETTY] |

For two weeks they practiced during the day in a public park, fixing a steel cable to a tree and their car, and telling people that they were practising for a circus. They also had to practice how to use a bow and arrow.

On March 30, at 2pm, Holger and a friend pretended to be electricians, with wires and cables hanging from their necks, their bow and arrow disguised, and sneaked into a house in Schmollerstreet in East Berlin’s Treptow.

They waited for more than 13 hours in the attic.

After two failures, Holger managed to shoot an arrow from the attic of a five story apartment in the East across the Berlin Wall, where Ingo was waiting in a house in West Berlin’s Neukoelln district.

It took him nearly one hour to find the arrow, which was stuck in a bush.

A thin fishing line attached to the arrow was anchored to the back of a car. Next, a thicker fishing line was played out along the first line. To the end of this, a steel rope was attached.

They ran the 200 metre-long steel cable over the part of the border known as the ‘death strip’, they fastened it to a chimney, his brother Ingo secured his end of the cable with his car and drove.

He told the defectors by walkie-talkie that it was fixed, and Holger rolled down it on two little wooden rollers. But the decline of the two buildings was less than they had thought. Holger stopped and had to swing his legs up on the rope and crawl the rest of the way.

For about ten seconds they were hanging 22 metres above the Berlin Wall, expecting the guards to shoot at them, but Holger had seen the guard before and to his astonishment he seemed to be asleep. When they reached the other side they looked at each other and could not believe they had made it.

| Three brothers, three escapes |

Ingo, Holger and Egbert Bethke fled East Germany one by one in dramatic style.

In 1984 Egbert Bethke, the youngest of the Bethke brothers, refused an offer by the East German auhtorities to legally leave the GDR, because his girlfriend told him she would commit suicide if he went to West Germany. But he wanted to leave, like his brothers before him, and it had to be something spectacular.

Ingo and Holger, his brothers in the West, devised a plan. It was nearly impossible to cross the wall by climbing or digging a tunnel, so they decided to fly.

Ingo took some ultralight flying lessons, and taught his brother how to fly a plane – illegally in Belgium. They sold their bar and bought two ultralight planes, changed the engines for stronger ones and brought the planes to Berlin.

Their first attempt on May 11, 1989 failed.

Two weeks later, on May 26, they tried it again. To confuse the boarder guards, they had painted Soviet stars on their planes. They dressed in military uniforms and helmets with microphones and started their planes.

Meanwhile, Egbert was waiting in the Treptower Park in East Berlin, hiding in the bushes, worried about being shot.

When he saw his brother Ingo landing in his plane, he ran towards him, jumped into the plane, and they took off again.

Holger stayed in the air observing the surrounding area. Both planes flyed at 150 metres above the Berlin Wall. No one noticed them.

At 04.37 they crossed the border, landing seconds later in front of the Reichstag building.

| Three hundred shots |

|

| Peter Fechter, like many others, was shot dead in his attempt to escape [EPA] |

On September 13, 1964, Michael Meyer, a successful jockey, tried to escape his enclosed life in the GDR.

“Everything was too narrow for me, I wanted to get out,” he said.

He drove towards the border under the cover of darkness. His plan was to swim across the River Spree to West Berlin.

But when he came out of the water after swimming for 30 minutes, he realised that he was still in the East.

“I thought they would arrest me immediately, but no one actually noticed,” he said.

At 05.20 Michael stood in front of the barbed wire fence, near Checkpoint Charlie.

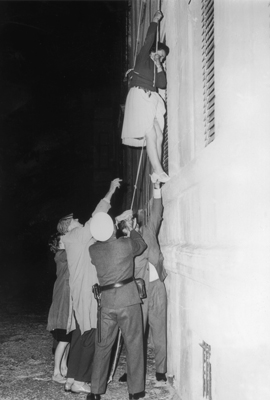

“I went beneath the wire – and the border guards started shooting.”

Later the Stasi noted that 300 shots were fired at the “border violator”.

Meyer was hit by eight bullets, one hit his right arm. both of his legs were hit and another hit his back.

The US soldiers on the Western side of the fence heard the shooting and came to help. US Sergeant Hans-Werner Pool climbed the wall and tried to help Meyer over but two border guards on the other side tried to pull him back.

Pool threw a gas grenade, the border guards backed off and Meyer was able to climb the wall with the help of a rope Pool threw for him.

Severely injured, he was taken to the hospital. He lost four litres of blood and knew that he was lucky to be alive.

The 66-year-old still has a bullet in his back to remind him of his escape. He never again heard from the US soldier who saved his life.

| Checkpoint Charlie |

|

| Military personnel in a car pass through the US army’s Checkpoint Charlie [GALLO/GETTY] |

Peter Spitzner, a teacher from Chemnitz, became the last person to successfully escape East Berlin via Checkpoint Charlie.

His wife was allowed to travel to Austria to attend her aunt’s birthday. Spitzner, who wanted to follow his wife to the West, read in a newspaper that US soldiers were not checked when crossing the border.

He took his seven-year-old daughter, drove to East Berlin and told her that they were going to visit her mother, but had to hide.

But all the US soldiers he met during his first two days in Berlin did not want to risk helping him. It was forbidden for them to help people escape the East.

But on August 18, 1989, one young American, Eric Yaw, agreed.

Spitzner and his daughter hid in the back of the car, which traveled through Checkpoint Charlie unchecked.

His only moment of panic came at the border when he felt the American’s car reverse and he feared discovery. But Yaw was only in the wrong lane.

His wife did not know anything about his escape and he needed to get the message to her before she returned to the GDR. He tried to reach her by telephone but could not get through, so he left a message saying ‘Ingrid, don’t go back to the GDR’ with the guesthouse she was staying at.

She received the message just in time and instead of returning to the GDR, flew to West Berlin where she met her husband and daughter.