Pursuing al-Qaeda in Horn of Africa

Ten years after al-Qaeda first surfaced, the US is still at war with “terrorist” groups.

|

| Survivors of the US embassy blast are pulled out of the rubble on August 7, 1998 [AP] |

In a neatly manicured garden in Nairobi, Joash Okindo limps towards a marble plaque erected in honour of those who died when an al-Qaeda cell simultaneously blew up the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania 10 years ago.

The attacks in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, which killed more than 220 Kenyans, Tanzanians and Americans and injured more than 5,000, brought the stark threat posed by al-Qaeda into global perspective for the first time.

“At ten in the morning, a yellow pick-up truck approached me,” recalled Okindo, the senior security guard at the Nairobi embassy’s rear gate on August 7, 1998.

“The front passenger was a jovial man, but he refused to look me in the eye as he told me he had a parcel to deliver to a diplomat,” Okindo said.

Their behaviour caused Okindo alarm. Worse, they lacked the proper paperwork for their hidden cargo.

“I persuaded the passenger to allow me to call the shipping staff to come with keys even though I had a set in my pocket,” Okindo recalled.

“The extension was busy but I told him someone was coming. The terrorists started talking to each other in a language I didn’t understand.”

The security guard refused the three men access to the embassy’s basement. Panicked, the occupants of the car pulled out handguns and grenades.

Okinda sensed imminent danger, ran across the road and took cover.

He came round as US marines dug his bloodied body out of the rubble of a collapsed building.

Opening salvo

The co-ordinated bombings became the opening salvo from a group bent on attacking American interests in Africa.

“It was a tremendous wake-up call. It was the first time we saw al-Qaeda surface in a formal way,” Michael Ranneberger, the current US ambassador to Kenya, said.

“It re-energised the US in re-focusing our efforts and realising the dimension of the terrorist threat we faced,” he added.

Ranneberger says US counter-terrorism policy in the Horn of Africa went beyond the desired elimination of terrorist suspects and their assets.

“It was recognised from the outset that there needed to be parallel approaches. One was to track down the culprits and bring them to trial. [The second] was the need to build and develop democratic institutions.”

In November 2002, al-Qaeda struck Kenya once more when two suicide bombers attacked the Israeli-owned Paradise Hotel near Mombasa, killing 13 people and wounding dozens.

At the same time, a second cell tried to shoot down an Israeli chartered airliner taking off from Mombasa’s airport with surface-to-air missiles.

New battlefield

|

| Somalia is a battleground between Islamist militias and government troops [EPA] |

By 2002, the Horn of Africa had become a leading front for America’s so-called war on terror.

Kenya, a relatively stable democracy in a volatile region with porous borders, has developed into a key US ally, a base for the super-power’s counter-terrorism activities in the Horn of Africa.

In October 2002, the US set up the Combined Joint Task Force–Horn of Africa in Djibouti, now home to more than 2,000 people including US military personnel and Special Forces.

In between the two countries lies Somalia, which the US has in recent years accused of harbouring al-Qaeda operatives.

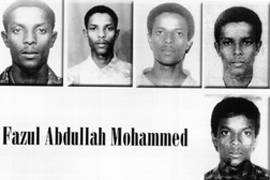

High on the FBI’s most wanted list is Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, widely regarded in security circles as the one-time leader of al-Qaeda in East Africa and the mastermind behind the embassy and hotel bombings.

Mohammed is believed to have spent years seeking easy refuge in the chaos of Somalia, a country that western intelligence reports say is becoming a breeding-ground for militias and radical groups.

He reportedly became a senior official in the Union of Islamic Courts (UIC), which won control of large swathes of Somalia in 2006. In December 2006, Ethiopian troops backed by US intelligence and airpower routed the UIC from de-facto power.

Since then it is believed Mohammed has moved in and out of Kenya.

Early in August 2008, Mohammed eluded an attempt by US-trained Kenyan anti-terror police to seize him in the coastal city of Malindi.

Targeted community

Kenyan police have raided houses along the Swahili coast and in Nairobi in the days that followed Mohammed’s bungled arrest.

Anti-terror forces have apprehended several individuals believed to be associates of Mohammed.

Kenya police say the net is closing in on the wanted man.

“Police have reason to believe that the suspect, Abdullah Fazul, will soon be arrested,” police spokesman Eric Kiraithe told Kenya’s Daily Nation newspaper.

But the arrests have upset the Muslim community which frequently accuses the Kenyan government of discrimination.

Al Amin Kimathi, the director of the Muslim Human Rights Forum, lays the blame for Kenya’s actions on America’s counter-terrorism policy.

“It [US counter-terroism policy] has had a large, negative impact on our community, in a sense criminalising Muslims and Islam in Kenya,” he said.

“One thing Muslims here feel is that generally the US is out to suppress Islam.”

Kimathi says there has been an upsurge in anti-western rhetoric, notably within Kenya’s coastal Muslim community. Local imams accuse the Kenyan government of being a US puppet.

“Extremists will not lack an audience. On the coast, and where people are in touch with what is going on in parts of the world where the US is blamed for repressive measures, it is easy to find people who might identify with that cause never mind how outrageous it is,” Kimathi said.

Anti-terror dividends

|

| Mohammed managed to elude capture in Kenya in August 2008 [Photo Courtesy of FBI/GETTY] |

Some analysts agree that US foreign policy has contributed to the increasing radicalisation of some Muslims along the Kenyan coast.

“US policy has made it easier for those seeking to portray the West as morally corrupt to do so,” Tom Cargill, the director for Africa at Chatham House, said.

But the US considers its counter-terrorism policy in the Horn of Africa a success.

“Since the embassy bombings there’s been tremendous progress in efforts combating terrorism,” Ambassador Ranneberger said.

“If you look at the last 10 years, al-Qaeda’s ability to operate in this area has been severely degraded.”

Western diplomats and analysts broadly agree that America’s campaign to isolate al-Qaeda in the Horn of Africa has succeeded.

“There may be remnants who are still in there,” said one western diplomat, “but I think al-Qaeda East Africa is lost.”

Game plan

|

| Okindo is still haunted by the attacks on the US embassy in Nairobi |

Nonetheless, the Horn of Africa appears to remain a central jigsaw piece in al-Qaeda’s game plan. Last year Osama bin Laden, its leader, called on Islamist fighters to defeat Somalia’s US-backed Transitional Federal Government, which he branded a western proxy.

Kenya’s border with Somalia remains closed. But the reported movements of Fazul Mohammed are an indication of how permeable this frontier is.

As the summer days of August wind down, Kenyans continue to remember and mourn lost friends, relatives and countrymen who died in the blasts 10 years ago.

But they are also asking whether America’s war on terror has made them any safer.

Okindo remains haunted by the Nairobi bombing. In recent years he has moved from one house to another, always looking over his shoulder.

“People might follow me. You know terrorists cannot forget, they have to revenge,” he said.