The Stream: GCC courts new kingdoms

Social media commentators analyse Saudi Arabia’s proposal to ask Jordan and Morocco to join with Gulf monarchies.

|

| Since the US abandoned its former Egyptian ally, Hosni Mubarak, in favour of pro-democracy protesters, Saudi Arabia has been looking to other Arab monarchies for support [EPA] |

It all started – as many stories do these days – on Twitter.

In May, rumours that Jordan and Morocco might be asked to join the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) spurred a flurry of tweets questioning the motives of Saudi Arabia, the main proponent of the project, and speculating on the respective incentives for this potential alliance.

At dinner tables across the Arab world many gawked at and mocked these apparent rumours. But soon it became clear that not only was this a serious proposal, but also that it could mark the beginning of a seismic shift in regional policy.

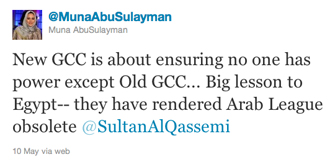

Muna Abu Sulayman, a Saudi TV anchor with the MBC broadcasting company tweeted:

New GCC is about ensuring no one has power except Old GCC…Big lesson to Egypt – they have rendered Arab League obsolete

Perhaps her claim is overstated. Still, the initiative can be seen as an effort by the six-nation group to counter the growing influence of Iran and to find new ways of defending common interests following the successful popular uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt.

|

“This movie is primarily about the internal politics of each country concerned,” said Steven Fish, professor of political science at the University of California Berkeley.

“The GCC plus Jordan and Morocco is a coalition of the trembling. Each of the timorous monarchs is far more afraid of his own people than he is of Iran, the United States, or any other external power,” Fish told Al Jazeera.

The Iranian threat?

Iran’s threat, whether perceived or real, intensified earlier this week when its military announced a new ballistic missile system, demonstrating the country’s advances in weapons production.

This followed the February arrival – and Egypt’s allowing – of two Iranian warships through the Suez Canal for the first time since the 1979 revolution.

“I don’t believe the Iranians take this seriously at all,” said Seyed Mohammad Marandi, an associate professor at the University of Tehran.

“Jordan and Morocco are unpopular dictatorial regimes that are firmly in the American camp. These regimes are weak and they are extremely worried about the winds of change sweeping through the region and they are in no position to influence events in the Persian Gulf.”

As Iran seems to be strengthening its footing, the region continues to witness unprecedented expressions of revolt from its people. After former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak was driven from power in a popular uprising, many Arab leaders, including those from GCC countries, took steps to appease voices of dissent and opposition.

Kuwait’s Emir, Sheikh Sabah al Ahmad al Sabah, ordered the distribution of $4bn and free food for 14 months to citizens, just three days after Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali was ousted from power on January 14.

On February 11 in Bahrain, prior to anti-government protests, King Hamad bin Isa al Khalifa ordered approximately $2,500 to be paid to every Bahraini family, according to the state news agency.

In Morocco, one week before anti-government rallies were held, the government announced on February 20 that it would offer approximately $2bn in subsidies to curb price hikes for staples.

And Jordan’s King Abdullah, who welcomed GCC leaders to his country on May 9 to wish them “every success in their joint Gulf work to achieve the nations’ ambitions and aspirations,” dismissed his government and appointed a new prime minister after three weeks of protests over rising food prices and the unemployment crisis.

Saudi Arabia also tried to quell its own voices of dissent, when on February 23 King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz announced $36bn worth of handouts. When this did not succeed in suppressing a flurry of protests across the country, he added another $67bn worth of spending on March 18.

A club for kings

In light of these developments, the GCC countries are hoping to strengthen their base by allowing Jordan and Morocco to join, despite having turned them down in the past.

|

The idea of solidifying a region-wide alliance and pooling resources from fellow monarchies looks all the more appealing.

Sultan al Qassemi, a UAE commentator on Arab affairs, tweeted:

Basically the GCC is turning into a club for Arab monarchies. #Morocco #Jordan

As the region scrambles to re-align itself within a fast-changing political landscape, the proposal to have Jordan and Morocco join the GCC highlights the anti-revolutionary roots of the group’s foundation in 1981.

The GCC was founded in part as a response to the revolution in Iran that took place in 1979 and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Among its main goals were plans to allow citizens to travel without visas and to develop a common currency and trade tariffs. Military cooperation was also one of its aims, but was never achieved, until Saudi Arabia’s deployment of troops to Bahrain last month.

Jordan’s armed forces, also known as the Arab Army, has more than 100,000 soldiers and the force is considered to be among the most professional and well-trained in the region. They have a relatively sophisticated special forces unit and almost all their equipment comes from the US, France and Taiwan.

Morocco’s military, founded in 1956, consists of almost 190,000 active personnel, with a similar number on reserve.

Both countries have well-trained Sunni armies which the GCC can call on to counter the “Iranian threat”, which some say is seen in Bahrain’s manifestation of civil unrest, as the majority Shia population are protesting against the Kingdom’s Sunni-led royal family’s rule.

While the Saudis and GCC have much to gain, at least militarily, from allowing Jordan and Morocco to join them, some are still sceptical.

“I don’t see what the Gulf is getting out of this,” said Ahmed al Omran, a Shia Saudi blogger made famous by his blog SaudiJeans.org.

“Economically Jordan will benefit a lot from this. If it becomes part of the GCC market, their labour force will have access to work freely in the gulf,” al Omran told Al Jazeera.

The much-needed economic incentives for Jordan and Morocco are clear. Both countries face high unemployment and serious budget deficits.

But perhaps most tangibly, the largest incentive would be that their citizens would be able to easily work in the Gulf, where employment opportunities are plentiful. Jordan and Morocco, like the rest of the GCC countries, are pro-Western, Sunni-led monarchies, but unlike the Gulf, their per capita gross domestic product is just around $5,000 whereas Saudi Arabia’s is $24,200 (2010) and Qatar’s, for example, is a whopping $88,000 (2010).

In March the GCC provided Oman and Bahrain with $10bn each over a decade to meet protesters’ demands for improved living conditions. This type of cash influx would immediately alleviate some of the economic problems troubling Jordan and Morocco.

Already the US is sending large amounts of money to the two countries. Overall US aid to Jordan this year is expected to surpass $700m, including the economic assistance plan announced last week by president Obama.

It is plausible that part of the reasoning behind the GCC initiative is that Saudi Arabia wants Jordan to know it can rely on Saudi too, not just the United States.

It is unlikely Jordan or Morocco will become full members anytime soon; instead it is likely that they will be granted observer status, which could begin with improved bilateral investments, but still with restrictions on travel and residency.

Still, if the GCC leaders want the Jordanian and Moroccan armies to be ready to die on GCC soil, they will need to provide full economic and travel rights. Currently, it is extremely difficult for Jordanians to get jobs and visas in many Gulf countries.

US role

The US was caught off-guard on January 25 when Egypt’s 18-day revolution began. It found itself in the role of a fair weather fan at a sports game, first supporting Mubarak and then quickly siding with the Egyptian people against him.

“There’s no question that the Saudi rulers, like other US-allied dictators in the region, despise the Obama administration’s quick abandonment of Mubarak and the rapid deterioration of its support for [president Ali Abdullah] Saleh after the popular uprisings started in Yemen,” Fish told Al Jazeera.

“The US would aid Saudi Arabia in the event of a real threat from Iran, and Saudi rulers know it. The question is whether the US would protect the Saudi government against its own people. Here, Saudi rulers fear – and rightly so – that the US government would not and could not protect them.”

These concerns mark what some are calling the beginnings of a souring in Saudi-American relations.

“There was a big disagreement over Mubarak and Bahrain,” al Omran told Al Jazeera.

“Saudis were supporting Mubarak and they did not want him to go, prompting King Abdullah to make two very angry phone calls to Obama in less than two months.”

Since then, Saudi Arabia has been campaigning to have other Muslim countries join an informal alliance at the cost of heightening sectarian divisions that would permeate the Arab world.

Should civil unrest sweep across the GCC, Saudi Arabia may fear that the US will, as was the case with Egypt, side with the people against the leader. So, it is looking to pursue new alliances.

The Saudis have been diversifying their exports of oil, rather than solely relying on the United States, which purchases nearly 15 per cent of Saudi’s exports (150,000,000 barrels) each year.

“For the last couple years, Saudis have been pushing for a more independent foreign policy, but also economically, they are selling more oil to India, China and Brazil,” al Omran said.

Through the potential GCC alliance, Saudi Arabia would inject massive amounts of cash flow into the Jordanian and Moroccan economies, in an attempt to shore up relations with the remaining monarchs in the region.

But as Professor Fish points out: “Obama does not want to be seen as a bully or as a self-righteous preacher; in this respect he aims to differentiate himself clearly from Bush. Saudi aid didn’t do Ben Ali or Mubarak much good; nor is it saving Saleh. The uprisings are demonstrating the limits of Saudi financial power to shape events in a region whose people are fed up with tyranny.”

Both Saudi Arabia, Iran and the US are vying for influence and trying to protect their interests in the rapidly transforming political scene in the Middle East.

After the announcements by president Obama to relieve up to one-billion-dollars in debt and guarantee another one-billion-dollar loan for Egypt, the Saudis last week pledged to provide Egypt with $4bn US dollars to support its economic recovery.

“I don’t think it’s really a matter of the US and Saudi Arabia competing for influence in the Arab world,” Professor Fish said, “but more a matter of Saudi rulers being more assertive in defending their fellow despots – and, by extension, themselves – given the Obama administration’s inability or unwillingness to prop up dictators in the region.”

Prince Waleed bin Talal al Saud, a high-profile member of the Saudi royal family, told The New York Times’ editorial board recently: “We’re sending a message that monarchies are not where this is happening… We are not trying to get our way by force, but to safeguard our interests.”

Although the Saudi Arabian ambassador Adel al Jubeir was sitting in the front row during Barack Obama’s first speech on the Middle East since the recent uprisings, Obama did not refer to Saudi Arabia once in the speech.

This omission of Saudi Arabia, Washington’s closest ally in the region, is indicative of the strained relations between them.

“Truth be told, the Arab revolts are very popular among the American people,” Professor Fish said. “Obama and much of Congress are facing elections next year and American politicians do not want to be seen – or characterised by their political rivals – as protectors of despotism.”

Hypocrisy and militarisation

Obama also made no mention of Saudi Arabia’s active support for the crackdown in Bahrain because it was the first instance of the GCC making use of its option to intervene in member countries’ conflicts. With Morocco and Jordan in the mix, this ability would be greatly strengthened and make the military option potentially more appealing than negotiations.

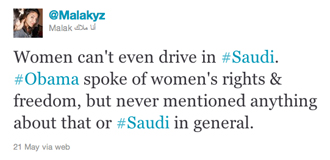

Obama spoke about women and freedom in his speech, but did not mention the women’s fight for freedom in Saudi Arabia or the sporadic protests across the eastern part of Saudi Arabia.

Malak Jaaphar noted:

@AJStream He gave a shout out to women & freedom but failed to mention Saudi Arabia? Hypocrisy.

As noticeable as Obama’s omission of Saudi Arabia was, he reserved some of his harshest words for Iran, accusing them of taking advantage of the turmoil in the region.

|

“Thus far, Syria has followed its Iranian ally seeking assistance from Tehran in the tactics of suppression. This speaks to the hypocrisy of the Iranian regime,” Obama said.

Marandi, the Tehran university professor, accused Obama of trying to justify what he calls “the crimes of the Bahraini and Saudi governments”.

“Obama attacks Iran for verbally supporting the oppressed people of Bahrain, yet he is completely silent about the brutal Saudi-led invasion and occupation of the country,” Marandi said

Jordan and Morocco’s military might aside, the UAE has already taken its own protective measures, hiring a company run by Erik Prince, the billionare founder of Blackwater Worldwide, to provide “operational, planning and training support” to its military.

Blackwater’s $529m contract with the Emirati government to recruit and train a foreign battalion for counter-terrorism and internal security missions highlights the much-desired ability to strengthen the GCC’s military capabilities, clarifying the logic behind the potential acceptance of Jordan and Morocco.

Singling out Iran and citing it as a justification is no longer convincing, al Omran said. “The Saudis and other countries in the region use Iran as a bogey man to justify their policies. Everyone is trying to increase his or her influence in the region. They say Iran is meddling in Lebanon and Bahrain – well, the Saudis are too.”

Ahmed Shihab Eldin is a journalist and multimedia producer who currently co-hosts The Stream on Al Jazeera English.