One year on, Indians still feel the pain of cash ban

Government claims demonetisation is a success but opposition says the move caused job losses and economic slump.

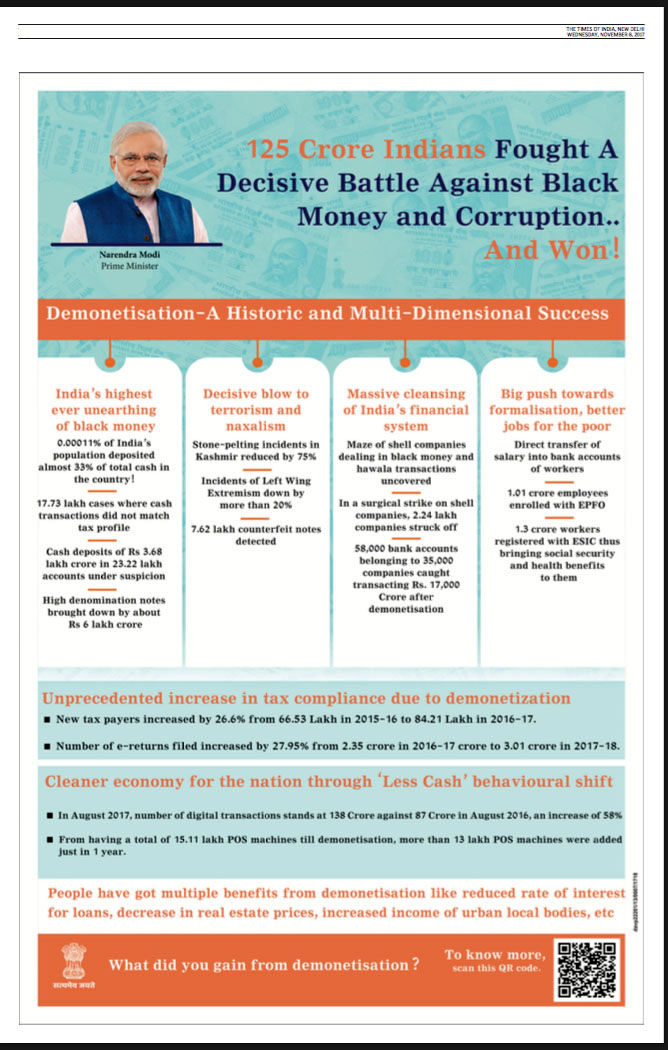

On Wednesday morning, Indians woke up to a celebratory advertisement by the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Advertisements in leading national newspapers and highway billboards claimed “Demonetisation: A historic and multi-dimensional success.”

The opposition, however, dubbed the government decision to ban high denomination notes a year ago on this day as a “monumental disaster” and a “tragedy”.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussia’s Putin eyes greater support from China for Ukraine war effort

India-Iran port deal: A gateway to Central Asia or a geostrategic headache?

India’s income inequality widens, should wealth be redistributed?

Modi’s shock decision was packaged as a game changer, a masterstroke, something which no country with an economy of this size had ever attempted. The drama around the announcement was as intriguing; on the evening of November 8, 2016, the media got a heads up that Prime Minister Modi was going to make an address to the nation, but no one had a clue what was coming.

Trying to justify its act, the government and the ruling party kept shifting the goal post - first, it was 'black money', then fake currency, then digital India and 'terrorism' funding.

What was delivered surprised and shocked the country – 86 percent of its currency was rendered illegal by executive order. What followed was complete chaos.

People were forced to stand in serpentine queues in front of ill-equipped banks; many of them questioned the wisdom behind the move.

One year down the line, growth figures are out for the first quarter, and as expected and predicted by critics the gross domestic product (GDP) rate is down to 5.7 percent – the worst in three years.

Opposition parties are saying this dip is essentially due to demonetisation. “Black Day” – that is how they are marking the day.

A year since the controversial decision, Modi, with lots of political capital on his side, remains defiant and insists he is on a mission to get rid of “black money” [illegal money or not declared to the tax authorities) from India.

His claims, however, are contested by the central bank’s report that states that nearly 99 percent of the banned notes returned to the banking system.

![India's main opposition Congress party supporters shout slogans during a protest on the first anniversary of the demonetization announcement, in New Delhi, India [Supreet Jayanna/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/4b0e78150ffb4968af1330eb1efc8316_18.jpeg)

History of demonetisation

For India, demonetisation is not new. The British colonial rulers had attempted a similar move, banning 500, 1,000 and 10,000 rupee notes a year before India was granted independence.

The ordinance of January 12, 1946, had provisions for up to three years of imprisonment along with a fine for violators. Newspaper clippings from the period reveal similar panic.

The British administration had hoped demonetisation would penalise Indian businesses that were concealing fortunes amassed during World War II.

Over three decades later in 1978, the Indian government decided to demonetise 1,000, 5,000 and 10,000 notes again with an objective to combat tax evasion and bring back “black money” held outside the formal economy. The move was criticised as an “extreme step”.

The first decade of the 21st century brought good cheer for the Indian economy – businesses were booming, but the period also saw a string of corruption scandals.

To battle financial corruption, the previous UPA government toyed with the idea of demonetisation again, but a committee of Central Board of Direct Taxes recommended against it in 2012.

The plan was shelved as the report noted that “black money” is largely held in the form of benami (nameless) properties, bullion and jewellery, not in cash.

Effects of Demonetisation

Besides the immediate impact of the inconvenience to people caused by the process of note swapping, its cascading effects were devastating for the job market.

According to data released on Tuesday by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the estimated total employment during the January-April 2017 period was 405 million compared with 406.5 million during the preceding four months.

The CMIE data also estimated that while the number of persons employed fell by 1.5 million from January to April 2017, the number of people who declared themselves unemployed fell much more, by 9.6 million.

This was essentially because of the near collapse of the informal sector of the economy. Various sectors like fishing and farming witnessed a sharp drop. Farmers were unable to even recover the cost of transportation, let alone make a profit.

The growth in core sectors like construction materials and refinery products, which constitutes 38 percent of the Index of Industrial output (IIP), decreased, and this had a negative wage implications for its casual workforce.

Shifting the goal post

Trying to justify its act, the government and the ruling party kept shifting the goal post – first, it was “black money”, then fake currency, then digital India and “terrorism” funding.

When all is said and done, “the proof of the pudding is in the eating” and elections early this year in India’s largest and politically significant state of Uttar Pradesh gave a thumping majority to the BJP. This was touted as a people’s stamp of approval to demonetisation, at least politically.

Politics continues to dominate this debate, with the government celebrating the day as #Antiblackmoneyday and opposition observing it as #BlackDay.

The Modi government now says the move will bear fruit in the long run. But former Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh might just have the last word on this, quoting British economist John Maynard Keynes, he said: “In the long term we are all dead.”

![Effigies depicting a wounded Indian economy is placed on a wheelchair next to mock bodies of people who allegedly died while standing in queues outside banks and automated teller machines (ATM) to withdraw money after the Nov. 8, 2016 demonetization, during a protest on the first anniversary of the demonetization announcement, in New Delhi, India [Supreet Jayanna/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/9822453add50412bb82cfda25b0c4edc_18.jpeg)