Afrikaners try to preserve language

South Africa’s Afrikaans language is perhaps best known for the word apartheid, but for a new generation of Afrikaans-speakers the most important word in their lexicon is “jol” – to party.

Tens of thousands of Afrikaners flocked to the western Cape town of Oudtshoorn on Monday for a week-long celebration of their language at the Little Karoo National Arts Festival.

Now in its 11th year, the festival has become one of the most important events in South Africa’s cultural landscape, offering a range of shows from rock music to theatre, art and public debate to opera, all in Afrikaans.

Even the works of Shakespeare and Federico Garcia Lorca have been translated into the language that gave the world the phrase “slegs blankes” – whites only.

Not that all Afrikaans speakers are white. The language is also the mother tongue for the majority of South Africa’s four million-strong mixed-race community which is increasingly staking its claim to the language.

But most of the festival-goers in Oudtshoorn are white Afrikaners, and there was plenty of evidence that this was an ethnic minority that fears for the survival of its language and its identity.

Legacy

From being the dominant force in South Africa for much of the last century, imposing the system of oppressive racial segregation known as apartheid, South Africa’s roughly 2.5 million Afrikaners have seen the tables turned.

|

“There are still two factions [in Afrikaans]. One faction wants to go back to before the Great Trek (the 17th century migration of Afrikaners into the South African Author Koos Kombuis |

Eleven years since the country’s first all-race elections, South Africa’s Afrikaners now complain they are denied jobs because of the colour of their skins, and some are locked in a bitter struggle with the black-led government over the right to

educate their children in their mother tongue.

Afrikaans, derived from the Dutch of the first white settlers and influenced by the Malay spoken by imported slaves, was for decades promoted by the apartheid government as the main language of white officialdom.

It sparked political outrage in 1976 when schoolchildren in the black Johannesburg township of Soweto took to the streets to protest against the forced teaching of Afrikaans in schools.

The government’s harsh response, which saw police shoot and kill one Soweto student, spurred escalating urban unrest which eventually persuaded South Africa’s white rulers to abandon their monopoly on power.

Now recognised as one of South Africa’s 11 official languages, Afrikaans remains politically fraught.

New reality

Some Afrikaners complain that it is being replaced by English in schools and universities and on radio and television as part of a plot to eradicate it altogether while indigenous languages such as Zulu and Xhosa benefit from government

programmes designed to encourage their use.

At the Little Karoo festival, Afrikaners demonstrated a range of reactions to the new reality.

Author Rian Malan, whose memoir My Traitor’s Heart is one of the most widely read books about modern South Africa, made his debut at the festival as a song-writer with an ironic take on the plight of his people.

|

|

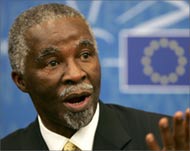

South African President Mbeki |

Audiences cheered Renaissance, a song named for President Thabo Mbeki’s vision of economic prosperity in Africa, which describes the trials of a white man looking for a job in a country where it is official policy to promote opportunities for the “previously disadvantaged”.

“Afrikaans has become a lot more attractive now that it is no longer the property of the NGK (Nederlandse Gereformeerde Kerk, a conservative religious denomination) and the Nats (the former ruling party during apartheid),” Malan said.

The waning influence of the straight-laced, conservative Afrikaner old guard was apparent in the popularity of a rash of irreverent Afrikaner rock bands.

New debate

Many Afrikaners feel they have much to apologise for, given the misery that apartheid meant for the black majority, but are trying to divorce the language from its links with apartheid architects like the late prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd.

“There are still two factions [in Afrikaans],” author Koos Kombuis told a public discussion at the festival.

“One faction wants to go back to before the Great Trek (the 17th century migration of Afrikaners into the South African

interior). That won’t work. We are not alone in South Africa. We must build bridges.”

And other Afrikaans-speakers argued that rethinking the connection between Afrikaans, Afrikaners and Africa might prove the language’s salvation.

“Who came up with the bad idea that Afrikaans belongs to white people?” coloured writer E K M Dido asked at a public discussion.

“This living flowing, flexible language with all its facets is mine, yours and all of ours … don’t try to oppress my language because Afrikaans stands back for no language in the world,” she said.