A way of saying ‘we shall overcome’: Playing football on Robben Island

The Makana Football Association was another way to resist apartheid by political prisoners in the South African jail.

Cape Town, South Africa – One morning in December 1967, prison warders strode into Robben Island’s Cell Block 4 with a football and randomly chose two teams of 11.

While walking to the grassless pitch they had cleared themselves, the prisoners hastily discussed tactics and came up with names for their teams: Bucks would play Rangers in the maximum-security prison’s first-ever organised football match.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIndia’s Rohit and Kohli skip white-ball leg of South Africa cricket tour

Australia channel Kali’s destructive power to beat South Africa in Kolkata

South Africa hold off New Zealand to win record fourth Rugby World Cup

The players were rusty, malnourished and exhausted from their backbreaking work in the island’s slate quarry. Barefoot, and wearing their khaki prison uniforms, they also had to contend with a vicious summer southeaster that whipped across Cape Town’s Table Bay.

“The game was riddled with poor passes … and the men’s lack of stamina and match fitness were obvious,” Chuck Korr and Marvin Chase wrote in More Than Just a Game: Soccer vs Apartheid. “None of this mattered to the players or the fans. For them, it was the most exciting event that had ever taken place on Robben Island.”

None of the 22 players involved that morning could have imagined that hundreds of Robben Island prisoners would go on to participate in organised football leagues for the next 23 years.

Anti-apartheid leader and former South African President Nelson Mandela – who died 10 years ago on Tuesday – stressed that the triumph over apartheid was a collective one. And the role of the Makana Football Association (MFA) is a story of such perseverance and unity that still resounds today.

Demanding the ‘right to play football’

In 1961, a year after white policemen massacred at least 69 Black protesters at Sharpeville, apartheid Prime Minister Verwoerd began sending political prisoners to Robben Island, a small outcrop surrounded by shark-infested waters and in the shadow of Table Mountain.

Verwoerd’s government saw to it that conditions were abominable. Just getting to the island was an ordeal: prisoners were shackled together and tossed into the hold of the boat which would take them the 10km (6 miles) from Cape Town harbour. By the time they arrived on the island, they were stumbling and covered in one another’s vomit.

Dikgang Moseneke, who was 15 years old when he was sent to the island in 1963, told Al Jazeera that it was the first time he ever saw the sea.

Apartheid was a highly legislated racial pecking order, with whites at the top and Black Africans at the very bottom. This permeated every aspect of life, both in and out of prison. Moseneke and the hundreds of other Black prisoners were allowed to wear only shorts – a reminder that they were just “boys” – and were forced to scramble for sandals from a communal pile every morning. “You were lucky if you got a left and a right shoe,” Moseneke recalls. “Never mind the right size”.

Reluctant to spend any money on people they viewed as “terrorists”, the government decreed that the prisoners should build their cells with rocks cut by their own hands. Until then, they would be crammed into the crumbling buildings built by the British. Work in the quarry was gruelling, Moseneke recalled, and the men were forced to endure frequent beatings by the white guards. But being next to the ocean was uplifting – and the long hours spent toiling together in the sun also gave a chance to talk and to organise.

“The biggest mistake the authorities made was to put us all together in that slate quarry,” former inmate Sedick Isaacs told the More than Just a Game docudrama based on the MFA before his death in 2012. Moseneke agrees: “They could have spread us across the prison system. I was 15, I would have been smashed and abused. Instead, I was put in a warm environment of learning and revolution.”

Robben Island brought together political activists from different parties and regions of South Africa. Most prisoners came from either the African National Congress (ANC) of Nelson Mandela or the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), of which Moseneke was a member.

In an attempt to reclaim their humanity, the prisoners campaigned for the right to education and the right to recreation. Football was an obsession for many inmates, and while they waited to play proper matches, they had clandestine kickabouts in their cells.

“We made soccer balls with anything. Pieces of rag. Paper. Anything,” Tony Suze, who went on to become one of the league’s star players, recalls in the docudrama.

The prisoners knew that presenting a united front was vital. For months on end, they made use of the official complaints channel to submit an identical demand: “We request the right to play football on the weekends.”

They were roundly ignored – until they embarked on a hunger strike in 1967. After 18 days of drinking only water, with many of the men in dire physical condition, the authorities – with the International Red Cross breathing down their necks – blinked first.

The prisoners could play football, provided they funded the entire exercise from the pittance they were paid for their work in the quarry.

The Makana Football Association

The chief warder was convinced that football would be a short-lived fad.

“In his white supremacist eyes,” Korr and Chase wrote, “not only were the prisoners too physically weak, they were also far too undisciplined to organise regular matches”.

The prisoners had other ideas. On the field, talented players like Suze and Dimake “Pro” Malepe took it upon themselves to improve the skills and conditioning of the men. Off the field, intellectuals like Moseneke and Isaacs set about organising a formal league according to FIFA regulations.

They decided to name it the Makana Football Association after a Xhosa warrior-prophet who drowned while trying to escape Robben Island in 1820.

“We decided to run it properly,” says Moseneke, who was unanimously elected as chairman of the MFA when he was just 20 years old. “We kept laborious minutes. We had a log which we produced every week. We had a referees’ association. We held disciplinary hearings.”

Moseneke, who was studying law by correspondence, was chosen to write the MFA’s constitution. Little did he know that 20-odd years later, he would be writing another constitution.

The players divided themselves into teams and designed kits for themselves, which were duly ordered from the mainland. Eight clubs were formed, mostly along political lines. The prize for the best name must go to Ditshitshidi (literally “Bedbugs”) and their unforgettable war cry: “Bedbugs will not let you sleep, they are a bother you can’t wish away.”

By far the most successful club, however, was Suze’s Manong FC, which admitted players of all political persuasions. Their on-field successes carried an important political message to the men of Robben Island: collaborate or perish.

For the teams in A Division, winning was paramount. But for the organisers of the MFA, it was important that everyone who wanted to play got a chance. To this end, they created three divisions and encouraged coaches to give all of their players – even “hopeless” footballers like Isaacs – a chance.

In this spirit of inclusion, prisoners also introduced a rugby league (the Springboks’ inspirational captain Siya Kolisi hails from a long and proud tradition of Black rugby in the Eastern Cape province), built their own tennis courts, and even organised a Robben Island Olympics.

Of course, there were challenges. On many a Saturday, the warders simply refused to allow the men out of their cells to play. And in 1970, a group of talented footballers led by Suze left their own clubs to form the Atlantic Raiders.

It was, says Moseneke with a smile, “very similar to what’s happening with LIV Golf … Except there was no money involved, only ego.”

Tom Eaton, who got to know five of the men involved while writing the screenplay for the More than Just a Game, said the episode still stood out for the men, 26 years after the fact.

“Suze was unrepentant, but I got the feeling from the others that the affair was seen as a threat to the overarching goal of the MFA which was to present a totally united front to the white supremacist government to prove that they were a bureaucracy in waiting,” Eaton told Al Jazeera.

In the early 1970s, football on the island appeared to be on its way out, as players got older and/or were released from prison. Somehow, the MFA managed to weather this storm until 1976, when the aftermath of the Soweto uprising saw hundreds of new prisoners being sent to the island – many of whom were young, fit and good at football.

The MFA, and the Robben Island community in general, were given a new lease of life, and organised football was played on the island until the prison was closed in 1990.

A lasting legacy

Very high-profile prisoners like Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Robert Sobukwe were housed in separate parts of the island and not allowed to take part in organised sports. But, says Moseneke, “they came to know about it, they could hear the cheers every Saturday morning”.

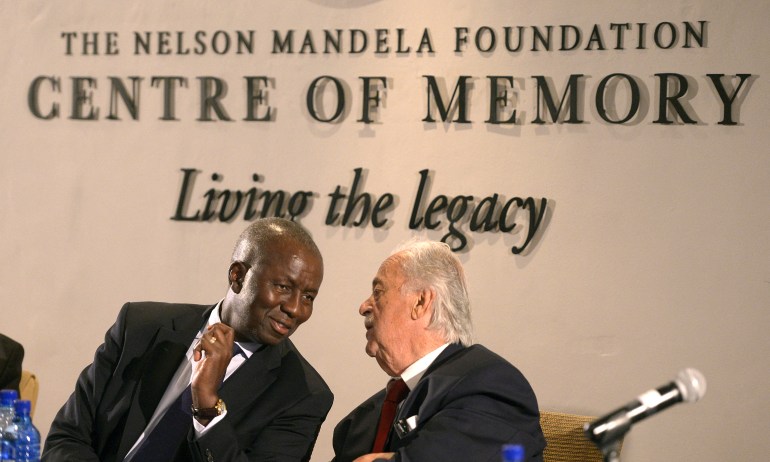

The MFA included many players who would go on to play prominent roles in the new South Africa. After his release in 1973, Moseneke qualified as a lawyer – he represented Mandela’s wife Winnie in her frequent run-ins with the apartheid government.

During the democratic transition in the early 1990s, he was one of eight people chosen to write the constitution of South Africa, and in 2005 he was appointed Deputy Chief Justice. Jacob Zuma – a skilful defender who attended a literacy class given by Moseneke – was elected president of South Africa in 2009.

And Isaacs went on to become an internationally renowned professor of medical informatics.

Eaton was struck by “how incredibly generous, compassionate and charismatic all five men were. They were genuinely upset about some of the young white warders who had committed suicide.”

And he could not help but notice that “most of them had stayed in community service, especially working with children” but they all seemed to have left active politics: “There wasn’t a political slogan among them.”

“Soccer wasn’t the only thing we had,” says Moseneke. “We had book clubs, we had chess clubs, we could study.”

But, he stresses, “soccer was the biggest thing in town and the only thing that got us out of prison clothes. Every single Saturday we re-engaged with ourselves and became these freedom fighters who would ultimately overcome. Soccer was the most prominent way of saying ‘we shall overcome’.”