Why Brazilian football fans are ditching the yellow jersey

Once an icon of unity and luck, the association of the shirt with Brazil’s far right has led football fans to give up on it.

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil – Higor Ramalho, an ardent football fan, plans to resume his regular trips to football stadiums as worries over the spread of the coronavirus ease, restrictions are lifted and the nation gets into the World Cup spirit.

However, the famous yellow jersey associated with the Brazilian national team has been hanging in his closet since June 2018. The last time he wore it was on his birthday. He does not know when, and if, he will ever wear it again.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsHow tattoos are helping overcome trauma, domestic abuse in Brazil

How Nigeria’s World Cup absence will affect businesses in Qatar

“Wearing the yellow jersey was a moment of pride for me,” the 33-year-old told Al Jazeera.

“It was a symbol of victory. I used to wear it not only while watching matches but also on regular days. Now, I have stopped wearing it for political reasons. The current president, along with his supporters, turned the yellow jersey into a political campaign and a symbol of their political party.

“And as I don’t support their political ideas, I refuse to be mistaken as one of them.”

The yellow jersey, known as the “canarinho jersey”, has not always been the Brazil national team’s shirt.

It was designed in 1953, three years after the World Cup final heartbreak at the hands of Uruguay in the Maracana. At the time, the national team wore white.

The national football governing body, along with a newspaper, launched a competition to design a new uniform for the national side, the condition being the new kit should have the colours of the national flag as the current did not carry “the idea of Brazilian nationality”.

More than 300 entries were submitted. The winning submission was by Aldyr Garcia Schlee, a Brazilian who felt torn by the 1950 result given that he was born on the border with Uruguay.

Fast forward many years, including a record five football World Cup wins and two Copa America triumphs, the yellow jersey had become a symbol of optimism, luck and unity among football fans.

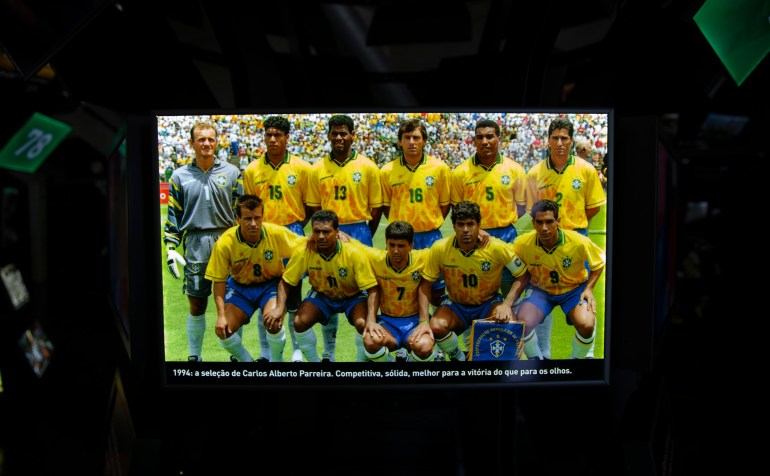

The number 10 worn by Pele during his mesmerising years on the pitch, Ronaldo’s number 9 when he became a World Cup winner and Romario’s number 11 during his dazzling World Cup 1994 run all became part of Brazil’s rich and successful history on the pitch.

But the shirt’s adoption in political campaigns, most recently by President Jair Bolsonaro and his right-wing supporters prior to his 2018 election win, forced a huge number of fans to give up on it.

Analysts say those same iconic moments of Brazilian football are being used off the pitch to promote ideas antithetical to the unity that made the national team, and the country, famous.

“Football is something iconic for Brazil, it is what brings everybody together most of the time,” Isabela Guedes, 25, told Al Jazeera.

“When they [right-wing supporters] take something so meaningful for the country and use it with political intentions, it is like they are stealing it from us. I don’t feel comfortable hanging a flag on my window during the World Cup because I will be mistaken for people with completely different political views.

“They have taken the flag and yellow jersey and turned them into political symbols.”

Co-opting the jersey did not start with Bolsanaro supporters. In 1970, the military dictatorship used the national flag and the team’s image, associating the essence of Brazil with the team, according to Carolina Fontenelle, a researcher at the Laboratory of Media and Sports Studies at UERJ.

General Medici, Brazil’s military leader at the time, also played a big role in the removal of the national team coach ahead of the 1970 Mexico World Cup.

With time, and these efforts, a strong connection was formed between Brazilians and their team’s jersey, she added.

“Since then, the yellow jersey has been perceived as a symbol. People look at that jersey and wear it with pride because they feel part of a group,” Fontenelle told Al Jazeera.

Before that, during the 2013 riots protesting a rise in the cost of living, corruption and police brutality, the jersey took on another aspect.

“People part of the riots were also wearing it. There was a high number of people on the streets protesting against many things, including the money spent on the World Cup 2014. In 2018, we had the far-right wearing the jersey,” Fontenelle said.

“So those who don’t agree with it start to feel ashamed. The jersey gives a feeling that you belong to a group and this feeling is lost when it is being used by a political group that doesn’t defend the minorities.”

“During the 2014 elections, the campaign of [centre-right candidate] Aecio Neves hijacked the colours of the Brazilian flag,” Fontenelle said.

#GiveBackOurFlag

Just over two years ago, a campaign, led by writer and filmmaker Joao Carlos Assumpcao, demanded the national football body abolish the famous yellow jersey and bring back the white and blue kit.

“We’re in a ghastly situation with a horrendous government that has stolen our flag,” Assumpcao had said at the time.

Several pro-democracy groups, including the Folha de Sao Paulo newspaper, tried to dissociate the colour with the far-right campaign.

In 2020, following campaigns by Bolsonaro supporters on the Supreme Court and Congress, it urged its readers to wear yellow as part of the dissociation campaign.

#DevolvamNossaBandeira (#GiveBackOurFlag) also got the backing of several political figures.

“Football is for everyone, I don’t like it [the jersey] being used by people who promote racism, sexism and discrimination,” Ademir Takara, the librarian and historian at the Museum of Football in Sao Paulo, told Al Jazeera.

“The shirt is the opposite of that. It represents unity and it’s not being used for that purpose. There’s an affectionate relationship between people and the shirt – the beautiful game attached to something it represented.

“From 2013, it has become a political thing more than ever before. It’s being used by people with different ideas who wanted something to unify them and the shirt was the easiest and strongest thing they saw.”

Earlier this month, thousands of Bolsonaro supporters flocked the Copacabana beach in Rio de Janeiro, among other cities, as part of a campaign push ahead of the October elections, just a month ahead of the Qatar World Cup.

Many of them wore the yellow jersey.

Former president Luiz Inacio Lula, tipped to win next month’s polls, lashed out at the demonstration on the anniversary of Brazil’s 200 years of independence.

“7 September should be a day of love and union for Brazil. Unfortunately, that’s not what is happening today. I have faith Brazil will recover its flag, its sovereignty and its democracy,” Lula tweeted.

With love for the jersey, football fan Marina Moreno told Al Jazeera how “frustrated” she was “to see the yellow jersey becoming a symbol of the current government”.

“Today, it is almost impossible to not associate it with the current president and his supporters. It’s automatic and it’s frustrating. I don’t support the current government and I don’t want to be mistaken for one of his supporters so I decided to don’t to wear it any more.”