The Factory

A glimpse into life inside Egypt’s Mahalla textile factory – a cauldron of revolt where workers inspired an uprising.

Filmmakers: Cristina Bocchialini and Ayman El Gazwy

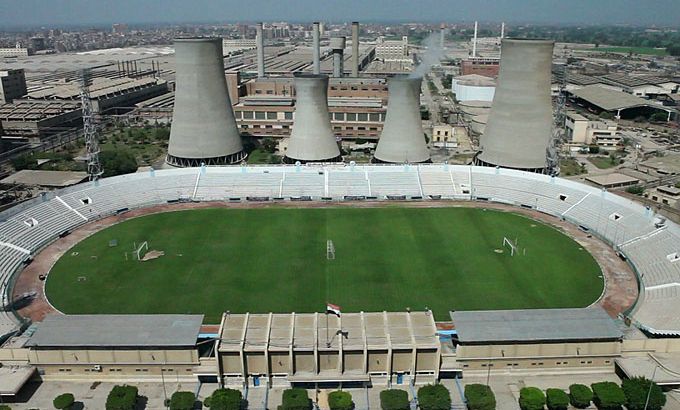

The El-Ghazl factory in Mahalla is Egypt’s largest textile company with more than 20,000 workers. It is a microcosm of Egyptian society.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsEgypt’s President el-Sisi to run for third term, opposition decry pressure

Tunisian police arrest two top officials in Ennahda opposition party

The Arab Spring is not dead

The factory has a reputation as a catalyst for protest.

In 2008, factory workers took to the streets demanding better working conditions. In January 2011, workers there were among the first to protest – prompting the mass protests that in turn developed into a revolution and led to the departure of Hosni Mubarak, the Egyptian president.

FILMMAKER’S VIEW

Mahalla El Kobra is a town in northern Egypt’s Nile Delta. It is the home of the Spinning and Weaving Company, the largest textile factory in the Middle East and Africa. Founded in 1927 by the Egyptian economist Talaat Harb, more than 20,000 workers now live and work on the 1,000 acre site.

It is surrounded by a high palisade over which nobody can climb and gates controlled by security personnel. It is through these gates that thousands of Ghazl El Mahalla workers rush every day – to hurry home, to buy food or to collect their children from school. Buses, trains and toctocs are crammed full of workers leaving as thousands more pass through another gate on their way to start their shift.

Inside the compound there are streets where children play and roads overflowing with cars and buses. There are stores, a cinema, a theatre, a library and a mosque. Workers can swim in the Olympic-sized swimming pool and play sports in the various sports clubs or in the green open spaces. A well-known football team even plays in the site’s stadium.

There is also a hospital and worker housing arranged around the factories. Power and water stations supply the houses and factories.

This is a city within a city; a microcosm of Egypt.

One big family

The first time we visited the factory we felt its power, its magic. While we had not originally understood why its workers felt such a sense of identification with and ownership of it, it immediately became clear once we were there.

In the 1930s, the factory operated just over 12,000 spindle machines. Today, it has 300,000. The factory is made up of 10 textile mills consuming one million quintals of cotton a year. More than five million items of clothing are produced annually.

Working at the factory is something that is passed on from one generation to the next – making it an integral part of the lives of those who live and work there and creating a sense that the workers are essentially one big family. They help each other – sharing money or food. During the numerous strikes that have taken place there, it was this type of support that enabled many to get by without an income.

In 1938, the workers went on strike for the first time. They demanded that their work pattern be changed from two 12-hour shifts to three eight-hour shifts. That moment marked the beginning of their fight for a fundamental change in the system.

A decade later, in September 1947, workers organised another strike to demand the reinstatement of colleagues dismissed for demanding better working conditions. Tanks entered Mahalla for the first time to suppress the workers. Three workers were killed and 17 injured.

When, in July 1952, a group of army officers led by Colonel Gamal Abdul Nasser overthrew Egypt’s monarchy, the workers at Mahalla were inspired. A month later, they went on strike in protest over long-standing grievances with the factory management. But they were in for a rude awakening – the strike was brutally suppressed by the army.

Unrest at the factory continued throughout the early 1980s and in February 1986, workers went on strike over their demand for a 30-day monthly wage rather than the 26-day wage paid by the company. The company eventually caved in but protests would soon erupt again.

Finding a political voice

In September 1988, Hosni Mubarak announced the cancellation of special school grants to workers. Within a few hours, 20,000 factory workers were out on the streets of Mahalla in protest.

While previous strikes had centred around economic demands and grievances over working conditions, workers had now begun to make more overt political demands.

The government responded to the strike with an iron fist and, to this day, many workers still remember the brutal treatment meted out to them by the security forces.

When, in April 2008, 10,000 workers took to the streets to protest against privatisation and corruption, they chanted “Down with Hosni Mubarak”. It was the first anti-Mubarak protest to take place since the president came to power in 1981 and it would serve as a spark for others.

The workers received widespread support from outside the factory walls. The large picture of Mubarak in Mahalla Square was pulled down and burned. A giant step was taken towards breaking the barrier of fear and a clear message was delivered to the regime.

The workers clashed with thousands of policemen who used tear gas and guns to quash the demonstrations. The battle in which the state used brutal force to silence unarmed and peaceful protesters would become engraved in the memory of the city. Hundreds of Mahalla citizens were arrested, dozens were injured and three, including a young boy, were killed. State security eventually occupied the city, taking over control of the factory.

But the courage of the Mahalla workers proved contagious. Other Egyptian workers learnt from Mahalla how to fight for decent wages and working conditions. Their plight came to symbolise the broader issue of deteriorating living standards for the majority of Egyptians and their activism the connection between economic and political demands.

Even now Mubarak has fallen, they say they will never stop fighting for social justice, freedom and dignity.

The filmmakers would like to thank: Hamdy Hussin for providing private footage for inclusion in the documentary and for his help with ensuring its factual accuracy; Nora Younis for providing footage of the 2007 strike; Philip Rizk for the footage of the 2011 strike; and Mohamed El Shennawy for the footage of the 2011 Cairo election uprising.