Boko Haram: Behind the Rise of Nigeria’s Armed Group

An investigation into the origins and ideology of the rebel group and its bloody rise.

Filmmaker: Xavier Muntz

Since 2010, people in northeastern Nigeria have lived in constant fear of being attacked.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTen years after Chibok girls kidnapping: One woman’s struggle to move on

Ten years after ‘Bring Back Our Girls,’ Nigeria’s kidnappings continue

Why mass kidnappings still plague Nigeria a decade after Chibok abductions

In the past years, Nigeria’s rebel group Boko Haram has repeatedly attacked schools, churches, mosques and markets, but state institutions such as police stations and military facilities have remained primary targets.

The group provoked global outrage in April 2014 when they kidnapped 276 schoolgirls in Chibok, northeastern Nigeria. The kidnapping received global condemnation and sparked the solidarity campaign #BringBackOurGirls.

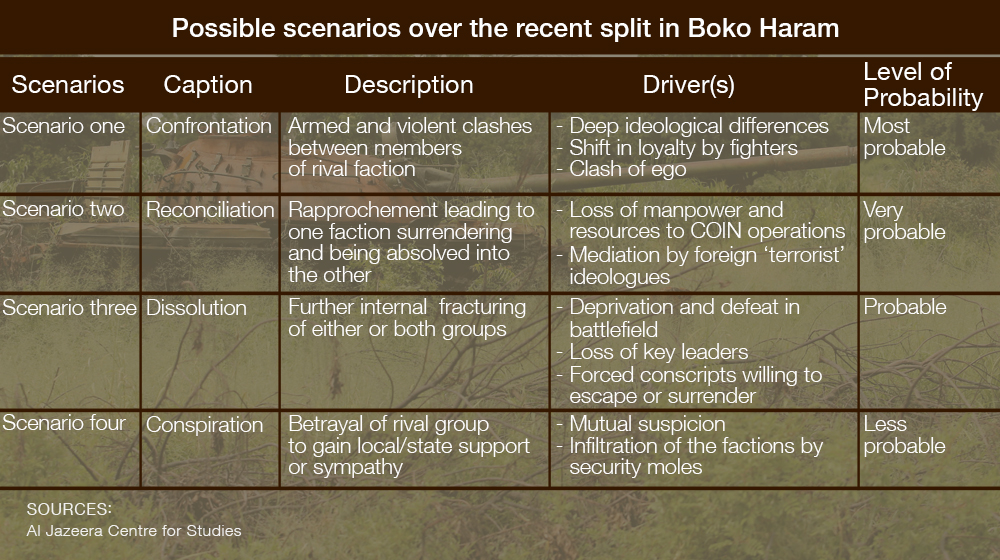

In August 2016, Boko Haram split into two factions after long-time leader Abubakar Shekau rejected an attempt by ISIL’s Abu Musab al-Barnawi to replace him. Al-Barnawi is believed to be the son of late Boko Haram founder Mohammed Yusuf and used to be Boko Haram’s spokesman. Sporadic fighting broke out between the two factions, one headed by Shekau and the other by al-Barnawi and some believe that the division could break the spine of the Nigerian rebel group.

Since the start of the insurgency, the violence has resulted in more than 32,000 deaths and over two million people displaced.

But how did Boko Haram emerge and rise to power? What motivates them and why do they continue to thrive?

This documentary explores the origins and ideology of the rebel group and its bloody rise to power.

![Some of the 21 Chibok schoolgirls released by Boko Haram during their visit to meet President Muhammadu Buhari In Abuja, Nigeria [REUTERS/Afolabi Sotunde TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/054e4d5c91aa4ad19e79e31412490a82_18.jpeg)

Mohammed Yusuf and the origins of Boko Haram

Boko Haram, also known as Jama’at ahl al-sunna li-da’wa wa-l-qital, was established in 2002 in the town of Maiduguri, northeastern Nigeria, by 32-year-old Mohammed Yusuf.

Yusuf set up his own mosque in a run-down neighbourhood ... People were intrigued ... There was a lot of curiosity in this radical rejection of the Nigerian state ... It was packed with people ... Yusuf fed the orphans and the street children. It became more than just a mosque.

With the return of democracy in 1999, Nigerians hoped for an end to widespread corruption within the elite and for fairer distribution of wealth.

To bring an end to corruption in politics, the Muslim majority in the north of the country wanted to see Islamic law applied more strictly. And Boko Haram took advantage of this popular demand.

“He [Yusuf] was quite a gifted preacher who became very popular because he was a good orator. And above all, he was a political preacher. It was that which spoke to his followers, the people of Borno. He talked a lot about lies… because for him, the politicians were liars,” says Elodie Apard, French Research Institute for Africa.

Yusuf’s message quickly resonated with people in the Borno region where the level of poverty was as high as 69 percent in 2011.

Nigeria is the leading economic power in Africa, but more than half of its population lives below the poverty line. Plagued by corruption, which is endemic among Nigeria’s elite, politicians have gradually lost the trust of the people.

“Poor people identified with this [Yusuf’s] discourse because they were promised paradise. They promised an Islamic state with Shariah, which is a form of social justice. Then the rich would no longer siphon off public money. They joined this group because they believed it would improve their lives through the more rigorous practice of Islam,” explains Marc-Antoine Perouse de Montclos, professor at the French Institute of Geopolitics.

READ MORE: The women who love Boko Haram

Nigerian authorities were increasingly concerned about the growing popularity of Boko Haram and Mohammed Yusuf’s influence on the people.

“Yusuf’s sermons were clearly against the state and were very violent in tone. Although Yusuf was not engaged in an armed struggle against the state, his discourse was contributing to it which was disturbing to the authorities. He was widely followed and really very popular. He became a threat,” Apard says.

In June 2009, a federal government task force stopped a group of Boko Haram members riding motorbikes as part of a funeral procession. The task force sought to enforce a law that required to wearing of helmets, but they refused to comply, and police officers opened fire on them.

“In a sermon that followed, Yusuf said that if the military was capable of killing people during a funeral, they had no respect for anything. They can come and kill you even if you are doing nothing. He said: ‘Now you have shown yourselves, you’ve killed us en masse, the next time you show yourselves, we will be ready. We will be prepared for you and when you come you will see. Then you will see what you are up against,'” says Apard.

![Since the start of Boko Haram's insurgency the violence has resulted in more than 32,000 dead [Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/934e16648bd84633a947b8ff04eacef1_18.jpeg)

The battle of Maiduguri and the death of Mohammed Yusuf

| Who is Abubakar Shekau? |

|

Abubakar Shekau became the leader of Nigerian insurgent group, Boko Haram, in July 2009, after the group’s founder, Mohammed Yusuf, was allegedly killed in police custody. According to experts, Shekau has neither the charismatic streak nor the rhetorical skills of Yusuf, but he has an intense ideological commitment and ruthlessness. Since he took power, Boko Haram has become more radical and violent. Under his leadership, the insurgency has spread to neighbouring countries, killed more than 20,000 people and driven more than 2.2 million from their homes. Shekau’s age is unknown, but he is believed to be in his 40s. He was born in Nigeria’s northeastern state of Yobe. He studied theology under local clerics in the Mafoni area of Maiduguri, then attended Borno State College of Legal and Islamic Studies for higher studies on Islam. He is believed to speak four languages, Arabic, Hausa, Fula and his native Kanuri. According to analysts, he is a loner and communicates with Boko Haram members through a few select confidants. The group communicates and claims responsibility for attacks by posting video or audio messages of its leader. The Nigerian military has announced Shekau’s death several times, but he has always reappeared alive on video. In March 2015, Shekau switched allegiance from al-Qaeda to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and declared that Boko Haram be known as the ISIL’s West Africa Province. In August 2016, ISIL, also known as ISIS, announced Abu Musab al-Barnawi as the group’s new leader, prompting a message from Shekau challenging the announcement of his replacement. Boko Haram has now split into two factions – one loyal to Shekau and the other to Barnawi. |

The outpouring of emotion triggered by the shooting provoked real tension among the followers of the group.

The sermons of Mohammed Yusuf were fierce, but behind the scenes the leader of Boko Haram urged caution. His position, however, became untenable. The hardliners of the movement, led by Abubakar Shekau, called for immediate revenge.

Bishop Naga Mohammed recalls the time in Maiduguri after the shooting:

“This time, it was terrible. The Boko Haram held the city at stake for almost a week. That was the genesis. We don’t know what had happened anyway, but later on they turned the town upside down. There was no Christians, there was no Muslims. Mosques attacked, churches attacked, all the civil societies have been attacked.”

The army intervened and according to Professor Perouse de Montclos there was a r eport by the government of Borno which was never published saying that 1,000 people were killed – most of them civilians.

The tension escalated and a full-scale military operation was undertaken in just a few days.

Some Boko Haram members died, some escaped, and Yusuf was arrested. While in jail, he was asked to reveal the name of his right hand, and he named Abubakar Shekau.

“He didn’t know he was going to die at that moment, he knew he was in a bad position. But Yusuf had been arrested several times before. He did not know that he would be shot 10 minutes later in the street,” says Apard.

Once arrested Yosuf had the right to been taken to court, but the government had given the order to shoot him.

“Yusuf was the dove of Boko Haram. Once he was killed, you have killed the dove. You have killed the structuring element of the group, which would disintegrate into small autonomous cells and clandestine groups. The vultures immediately took power after his extrajudicial execution in 2009,” says Perouse de Montclos.

The army’s role as a ‘recruiter for Boko Haram’

After the death of Mohammed Yusuf, the survivors of the battle of Maiduguri gathered in Niger to prepare their revenge. In July 2010, Boko Haram launched their first attacks in the state of Borno.

“Their target group was initially security forces and ‘bad’ Muslims, corrupt Muslims who were in government. It was not the Christians. But in 2010, Christian minorities were targeted with planned attacks,” says Perouse de Montclos.

The attacks against Christians provoked a widespread outpouring of emotion in the country. This added to the targeted murders of security forces, traditional leaders and politicians considered to be corrupt by the group.

After Boko Haram carried out a suicide attack on the headquarters of the national police in Abuja, President Goodluck Jonathan was forced to send the army to the northeast, but it was an army that was ill-prepared and poorly educated.

These people came with ignorance.... they perceived that everybody was Muslim. And if you are Muslim you are supporting Boko Haram, even though you are not supporting Boko Haram openly. So the army treated civilians the same as they treated Boko Haram.

“The soldiers sent to fight in Borno did not speak the local languages, so when they said ‘Hands up’, the people did not understand and didn’t raise their hands. They shot at the crowd. Every time there was an attack against the military, there were acts of revenge … Action. Reaction. So if the attack started in a certain neighbourhood, they would burn that neighbourhood …”

“This built the legend of Boko Haram and people wanted to join the group – not because they followed the ideas … but because they were afraid of the repression by the military … The army has played a big role as a recruiter for Boko Haram,” says Perouse de Montclos.

In May 2013, President Jonathan declared a state of emergency.

Boko Haram’s territorial expansion

The summer of 2014 marked Boko Haram’s year of territorial expansion.

The group seized several towns in the northeast of the country and the Nigerian army was on the verge of defeat. In the south of the state of Borno, Boko Haram took the town of Gwoza without any resistance.

Fear was imposed in the areas controlled by Boko Haram and the purging of what they called “bad” Muslims and the hunting of Christians continued and got worse.

“What is happening is not a jihad, it’s genocide. What are your objectives? What do you want to achieve?… It’s a faithless Muslim organisation engaged in carnage. And then unfortunately the media and the people took it as Islam, but there’s no Islam there,” says Adam Muhammad Ajiri, professor of Islamic studies, University of Maiduguri.

The civilians who fled the fighting and the massacres crowded into camps in the region. More than two million people, forcibly displaced, have lost almost everything and most of them are severely traumatised.

![Women who have fled violence in Nigeria queue for food at a refugee welcoming centre in Ngouboua, Chad [Reuters/Emmanuel Braun]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/44226df1f5d9463a8d9fa6e5432fbcc2_18.jpeg)

Technical defeat: ‘They won’t kill the ideology’

As Boko Haram continued to advance, France – at the request of then Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan – organised a summit to discuss security in the region. An international military coalition was formed and the armies of neighbouring Chad and Niger now had the right to pursue into Nigerian territory.

After several months of fierce fighting, the coalition managed to drive Boko Haram from the large cities in the state of Borno. In December 2015, Muhammadu Buhari, the new Nigerian president, declared that Boko Haram technically defeated.

Even though Boko Haram has suffered many military setbacks against the international coalition, the group still threatens isolated villages in the region – challenging the claim of victory by the Nigerian military.

“They may crush the movement, but they won’t kill the ideology, which is based on the gap between the rich and the poor in Nigeria. The ideology it brought, that Yusuf started, can spread everywhere. Even if the movement has been crushed, maybe in two or three years time we will have to see what they do and where it will re-emerge,” says Apard.