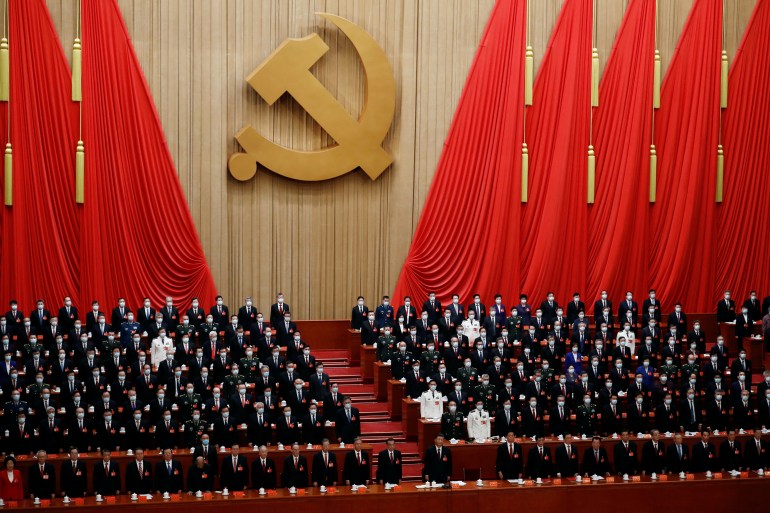

From the Party Congress in China to the midterm US elections

The Take looks at China’s latest Party Congress and its political implications within and outside the country.

The dust has settled on China’s Communist Party Congress. The party holds the gathering every five years and it is the political event to watch. This is also the case in the United States, where politicians from both major parties are bringing up China ahead of the country’s midterm elections. In this episode, we look at what the outcomes from the latest Congress could mean for China’s people and the country’s relationship with the US.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsA football player’s journey from Mali to Belgium

In Syria, facing cholera and corruption

Is Percy Lapid’s murder a bellwether for the Philippines?

In this episode:

- Yangyang Cheng, (@yangyang_cheng), research scholar at Yale Law School Paul Tsai China Center

- Isaac Stone Fish, (@isaacstonefish) CEO, Strategy Risks

Connect with us:

@AJEPodcasts on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook

Full episode transcript:

This transcript was created using AI. It’s been reviewed by humans, but it might contain errors. Please let us know if you have any corrections or questions, our email is TheTake@aljazeera.net.

Halla Mohieddeen: The dust is settling on China’s latest Party Congress. The Communist Party of China holds the gathering every five years, and it’s the political event to watch. With it comes new reports from party leadership, like President Xi Jinping, that observers scour for details, hoping for clues about where China might be headed over the next few years. And for some, hope is narrowing.

Yangyang Cheng: I think what was interesting, from the Party Congress was how much of it was not really so surprising, in a sense was, ‘Oh, this is a trajectory that’s a long time in the works,’ even though it is an extremely grim prospect.

Halla Mohieddeen: So what could those prospects mean – both for people in China, and people outside, worried about potential conflict? I’m Halla Mohieddeen and this is the Take.

[THEME MUSIC PLAYING]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Halla Mohieddeen: Yangyang Cheng moved to the US from China back in 2009 to get her PhD in physics. And she worked in the field until fairly recently.

Yangyang Cheng: And then about two years ago, in the middle of the pandemic, I made an unconventional career switch. I’m now a research scholar in law and fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, where my research focuses on the development of science and technology in China and US-China relations.

Halla Mohieddeen: It might sound like a big change, but Yangyang says it felt natural.

Yangyang Cheng: I was born and raised in China, and when I was growing up I was told that basically politics and death are the two biggest taboos. Had I grown up in a free country, quote-unquote, I might have chosen a very different career path.

Halla Mohieddeen: But science, she says, offered her more opportunity without compromise. So she studied physics and rose in her field – even working on projects like the large hadron collider, where physicists from around the world come together to study matter at its most basic form. And then around 2016, there were …

Yangyang Cheng: A lot of geopolitical earthquakes that was happening, I guess on both sides of the Atlantic.

Newsreel: China’s communist party has sharply expanded President Xi Jinping’s political power, anointing him as the country’s core leader.

Newsreel: Donald Trump wins the presidency of the United States.

Yangyang Cheng: And I felt that even though I still do love my physics work, the work that is related to policy has more urgency.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Halla Mohieddeen: Let’s turn to politics then and almost your new field if you like. The recent Party Congress that has just wrapped up in China has been quite remarkable, hasn’t it? There’s been some indications that Xi Jinping’s hold on power is solidifying. Was there anything that you noticed that might indicate that?

Yangyang Cheng: I think what was more interesting in times of Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power was seen not so much in what was said in a Party Congress reports, but in terms of who were quote-unquote, elected, or selected into the Politburo, in particular, the standing committee.

Halla Mohieddeen: The Politburo is one of China’s most important decision-making bodies. It has 25 members. And the most important seven of those members make up the standing committee, which is led by Xi.

Yangyang Cheng: The way it’s being stacked with his loyalists in an almost, like, absolute faction. And one particular personnel choice that struck me was Li Qiang, the second in line, who is most likely going to be premier next year.

Halla Mohieddeen: Before this month, Li Qiang was most known for being the party secretary in Shanghai. And earlier this year, under his tenure, Shanghai was known to have one of the most restrictive COVID lockdowns.

Newsreel: People in Shanghai are losing their patience for the city’s strict coronavirus lockdown.

Newsreel: People are being confined to their compounds, their houses, their apartments, You get the occasional delivery here, but that is about it.

Yangyang Cheng: One might have thought that this might be a tarnish on an official’s career, but apparently he’s being promoted for it. And I think that implication probably means that the building of state capacity, these surveillance and control infrastructure, in the name of COVID-19 prevention are going to be a daily reality of Chinese life for a very long time to come.

Halla Mohieddeen: It’s fascinating, isn’t it? Because if you’re not familiar with the way the Chinese political system works, it can be quite infuriating watching from the outside. It’s so choreographed, so opaque, and you’ve just laid out there quite clearly that, you know, having one person moving into a particular job that gives a real insight into what could lie ahead for China’s political governance.

Yangyang Cheng: I think that is an interesting point, and I think on one hand, looking at these small developments, in terms of personnel and in terms of like, say the Party Congress report, what is probably more interesting than the report itself is the changes in these specific phrases. How many times they’re mentioned, certain phrases appearing or disappearing. These shifts are probably more informative than just a singular text itself.

Halla Mohieddeen: And we’ll get to those shifts in a minute.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Halla Mohieddeen: But first, there’s a moment that Yangyang noticed – along with a lot of other people watching the congress.

Newsreel: Questions are still swirling about an incident involving former President Hu Jintao. He was escorted out of the main auditorium in the Great Hall of the People on Saturday

Newsreel: Was Hu ill or defiant? Was he purged? Pick your theory. We’ll probably never know.

Halla Mohieddeen: Hu Jintao was president of China from 2003 until 2013. And there’s been a lot of speculation as to why he was removed from the hall. State media later said he was suffering a health episode, and Yangyang says she doesn’t have a reason to dispute that.

Yangyang Cheng: However, I think what was probably more telling is the reactions from his colleagues while he was being escorted out of the venue. No one turned around to look at him.

Halla Mohieddeen: Here’s Yangyang’s interpretation of what happened.

Yangyang Cheng: This is a climate of fear and paranoia, so no one could turn around to look at a former leader because they do not know how their reaction might be interpreted as a sign of political allegiance or personal loyalty.

Halla Mohieddeen: Because as a former party leader, I mean, that’s a role that traditionally carries an enormous amount of respect, isn’t it?

Yangyang Cheng: Yes, but also just even if he was not in the top leadership, even, he was just an ordinary delegate, there is still some kind of reaction. And so I felt on that level of rigidity, that level of orchestration that the show must go on. And that is by itself a demonstration of power.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Halla Mohieddeen: Let’s talk about some of the things that Xi actually laid out in his reports. He mentioned security more than the economy, and that seems to be a first. What do you think’s behind that change?

Yangyang Cheng: I think security was mentioned about 90 times. Economy was mentioned about 60 times. However, I should also note that the word development, fazhan, was mentioned over 200 times. So I wouldn’t necessarily see this as a shift away from economic development or the economy in general. But I think what this indicates is what kind of development. For example, if we look at the Chinese government’s policies in Xinjiang with these brutal crackdowns and surveillance and mass internment.

Halla Mohieddeen: Policies that the UN examined earlier this year.

Newsreel: Michelle Bachelet’s long-awaited report is a damning indictment of China’s treatment of the Uighur population. It found that Uighurs and other mostly Muslim groups held in detention camps have been subjected to torture.

Yangyang Cheng: A lot of that is down in the name of security and counterterrorism. But a lot of that is also done in the name of development.

Newsreel: China has condemned the report. It says its policies in Xinjiang fight what it calls terrorism, and provide Uighurs with better economic opportunities.

Yangyang Cheng: So when we see this emphasis on security and the emphasis on development in the latest party report, I think the questions we need to ask is what kind of development, what motivates it, and whose interest it serves.

Halla Mohieddeen: And so what kind of development do you think that, that Xi is pursuing then, and whose interests is he hoping to serve?

Yangyang Cheng: I think it is a little bit too early to tell. But in general, I think any kind of policy, from Beijing and from the Chinese leadership is, first of all, to serve the interests of the party in the sense of solidifying party control. Everything else comes secondary to that.

Halla Mohieddeen: It’s hard to tell what people across China might think about Xi’s reports, but we did get some form of dissent ahead of the meeting in the form of a single protest on a bridge. Can you tell me about what happened?

Yangyang Cheng: I remember that moment very, very clearly when I saw the videos. And initially, I didn’t quite understand what was going on. And then there were some discussions of just where this bridge was, and I think it was confirmed both by the geolocation, but also because of Chinese censorship that the name of the bridge and the surrounding neighbourhood was quickly being censored on Chinese social media.

Halla Mohieddeen: We now know the location to be Sitong Bridge, which sits over a busy Beijing overpass.

Yangyang Cheng: And then the message itself is absolutely remarkable.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Yangyang Cheng: The banner said in this kind of fashion, buyao, yao. So he says no to confinement. We want freedom. No to continuous PCR tests. We want to be able to eat. No to the dictator. We want to vote, in this really succinct but also really catchy phrasing. And then there is another side to the banner that basically said remove Xi Jinping the dictator from office.

Halla Mohieddeen: Protests happen often in China, Yangyang says, but they’re usually more directed at an individual grievance – say a labour issue, or a real estate dispute.

Yangyang Cheng: But this message on Sitong Bridge was directed directly at the top leadership and at Xi Jinping himself. That boldness and that directness, I do think it is a moment that will be remembered in Chinese protest history.

Halla Mohieddeen: The bridge protester’s act of defiance has already inspired others to speak out, too.

Yangyang Cheng: So we see that these reverberations across China with other people, scrawling a message on the door in the public restroom, which is probably the only public space in China that’s outside the ubiquitous surveillance by the Chinese state.

Halla Mohieddeen: There have already been comparisons with the famous tank man, who obstructed Chinese security forces in Tiananmen Square back in the 1980s. But Yangyang says she’s reminded of another Chinese dissident, Lin Zhao, who was imprisoned and eventually executed under Mao Zedong.

Yangyang Cheng: And during her imprisonment, she also at times used her own blood to write these letters and these poems denouncing Mao and denouncing the party’s policies. And that act, one would think, is just suicidal. But because Lin Zhao, with her irrepressible spirit of dissent, she left a mark. It was not that the entire country had gone into madness or silence. There was at least one voice. And so future generations can look back and find these little markers of hope.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Halla Mohieddeen: After the break, a look at how politicians in the US are using China as a political tool of their own, ahead of the country’s midterm elections.

Halla Mohieddeen: I’ve been speaking with Yale policy scholar and physicist Yangyang Cheng about China’s latest Party Congress. We also heard from others about what the meeting may have signalled.

Isaac Stone Fish: I think we do have to remember that politics dominates in China and national security is going to be a growing concern, which is why there’s so much more focus on security than economy.

Halla Mohieddeen: That’s Isaac Stone Fish. He’s a former journalist and the founder of the firm Strategy Risks. We asked him about how the US has been reacting to China. And there’s one risk in particular he mentioned:

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Isaac Stone Fish: Policy towards China is playing quite a large role in the US midterms because there’s a lot of worries in the United States, both about the Communist Party’s influence in America, but also the question over Taiwan. Both sides are perilously close to a war. If China decides to invade Taiwan, which it’s been very clear that it’s willing to do, the US very well might get involved in that war. And that could be a regional war. It could also very possibly be World War III. So it’s a major policy concern. It’s a major global issue, and it’s something that doesn’t get nearly enough attention.

Halla Mohieddeen: The potential for war might not be getting that attention. But US politicians have emphasised their concern over a potential Chinese incursion to Taiwan for some time. US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi made a trip to Taiwan herself back in August.

Newsreel: House speaker Nancy Pelosi arrived in Taipei just before 11pm local time.

Newsreel: Pelosi’s late-night landing was quickly followed by news of Chinese military drills all around the island.

Halla Mohieddeen: And it’s not the only part of US-China relations making it into the debate as the United States gears up for midterm elections. There’s concerns over spying.

Newsreel: Breaking news out of the Justice Department. Attorney General, Merrick Garland, has just announced arrests over alleged espionage involving the Chinese government.

Halla Mohieddeen: And a rising trade war.

Newsreel: Washington has imposed sweeping controls on exports of semiconductors, also known as microchips, to Beijing.

Halla Mohieddeen: Some candidates, like Democrat Tim Ryan, who’s running to represent Ohio in the US Senate, are even running campaigns around China, with ads like this:

Tim Ryan: China. It’s definitely China. One word, China.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Halla Mohieddeen: Here’s Yangyang again.

Yangyang Cheng: Think this is probably one of the most interesting developments coming from this midterm when we would usually think foreign policy is something that only affects presidential campaigns at the top level. How much of these local state races, including not just congressional races, but governor races, like the one in Georgia where China is being discussed so much, and not just by one party, but by both Republican and Democratic candidates?

Halla Mohieddeen: Take that example in Georgia, where Democratic candidate Stacey Abrams went after her Republican counterpart, Brian Kemp, for his policies that encouraged Chinese investment in the state’s farmland.

Stacey Abrams: Republicans and Democrats have raised the alarm over the rise in the Chinese Communist Party-backed companies purchasing American farmland. To date, they’ve purchased more than 1 million acres of farmland in the state of Georgia.

Yangyang Cheng: That is a fascinating development, but it’s also deeply worrisome. I think it is a sign of very unpleasant times to come.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Halla Mohieddeen: And it’s already hard for a lot of Chinese people working in the US right now, especially scientists. Part of this stems from a fear of surveillance. Former US President Donald Trump launched something called the China Initiative back in 2018, to prosecute what he considered to be Chinese spies in US research industries. And while current President Joe Biden ended the programme earlier this year, after outcry over concerns of racial profiling, the stigma is still there.

Yangyang Cheng: It is really difficult to be an overseas Chinese student these days when you are still new to a country, still pursuing a degree, studying, navigating a new environment, seeing the worrying developments in your birth country, but also seeing the rising hostilities here in the US, where Chinese students are either being seen as just cash machines for tuition income for their schools or being accused of being potential agents of the Chinese state, or carriers of the COVID-19 virus, that’s a very difficult position to be in, especially for young students.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Halla Mohieddeen: Over the past decade, we’ve seen a variety of types of China policy from the US government, and a lot of it focuses on science. Why do you think that is?

Yangyang Cheng: I think this is actually in line with why China is being a new focus in a lot of these local and state races, when a lot of these blames are being placed on Chinese investments in the US, manufacturing jobs moving to China. And so a lot of these problems that are being directed at China, are actually not problems with regards to China or the authoritarian political system of the Chinese state, per se. These are problems of capitalism.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Halla Mohieddeen: Yangyang says the issue here isn’t China versus US, democracy versus autocracy, or any of the binaries that get floated around. It’s more about money and capital: who has it, who doesn’t, and where it’s moving.

Yangyang Cheng: The Chinese economy over the past four decades transitioned to embrace the capitalist market. And this is why manufacturing jobs moved to China and such, right? Because it was in the periphery, and it’s where western interests, US interests can continue to extract profit from. And scientist students coming from China are very much being seen in this way. They are human capital.

Halla Mohieddeen: For a long time, the US welcomed Chinese scientists, people like Yangyang, because they were seen as a benefit to US companies. But as China’s profile grew on the world stage, that image started to shift.

Yangyang Cheng: Right now what we are seeing is China and the US are battling for control over the top position in this capitalist hierarchy. And this is the fundamental underlying reason for a lot of what these geopolitical tensions and these suspicions on scientists and technologies and intellectual property theft are coming from.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Halla Mohieddeen: As someone who’s lived in both countries, What do you think people should understand about the potential for a great power conflict between the US and China?

Yangyang Cheng: I think people need to understand that war is not inevitable. However, there are certain interests who may want a path to conflict as a way to solidify and accumulate power.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Yangyang Cheng: So I think what is more important at the moment is to see why powerful interests are so aligned in this narrative of whether you call it great power competition or strategic rivalry, systemic competition, whatever, why they are the ones who have so much power.

Halla Mohieddeen: And when it comes to challenging that power, Yangyang is also thinking about those pockets of dissent she does see – like the Sitong Bridge protester and the people he’s inspired.

Yangyang Cheng: In these difficult times, it is particularly important to hold on to these voices, to hold on to these hopes, and to help expand it and let it grow. And I think that is where freedom dreams can still bloom, even if it’s in a very dire situation.

And that’s The Take. This episode was produced by Negin Owliaei with Ruby Zaman, Chloe K Li, Alexandra Locke, Ashish Malhotra, Amy Walters, and me, Halla Mohieddeen. Our sound designer is Alex Roldan. Aya Elmileik and Adam Abou-Gad are the Take’s engagement producers. Ney Alvarez is Al Jazeera’s head of audio. We’ll be back on Monday.

Episode credits:

This episode was produced by Negin Owliaei and our host, Halla Mohieddeen.

Ruby Zaman fact-checked this episode.

Our production team includes Chloe K. Li, Alexandra Locke, Ashish Malhotra, Negin Owliaei, Amy Walters, and Ruby Zaman.

Our sound designer is Alex Roldan. Aya Elmileik and Adam Abou-Gad are our engagement producers. Ney Alvarez is Al Jazeera’s head of audio.