How to prevent a putsch

Most military coups are ‘inside jobs’ and can be prevented only by improving the overall state of a country’s domestic and foreign affairs.

Africa has seen more military coups than democratic elections in recent years, to the determinant of the continent’s stability, peace and development.

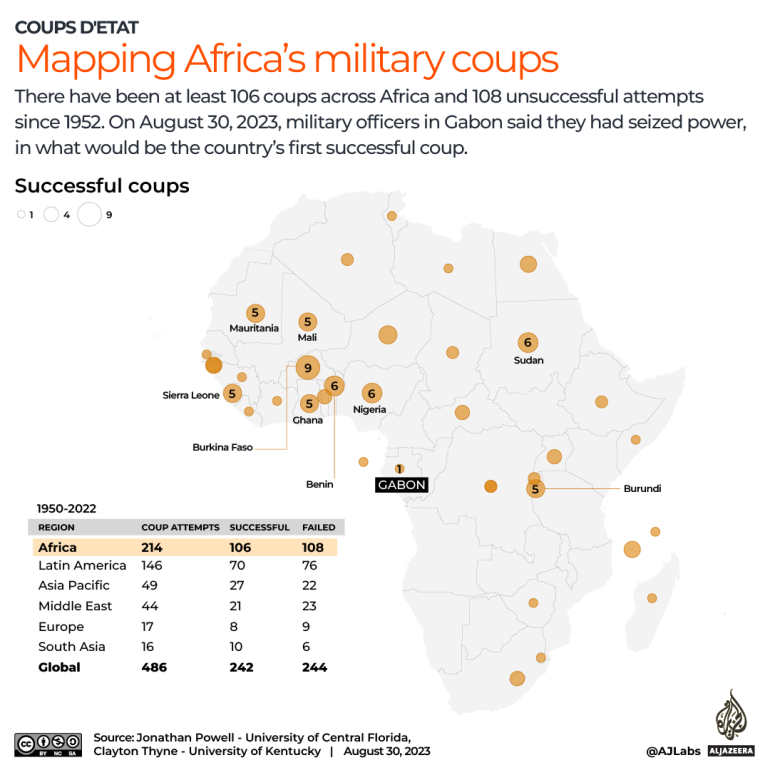

This week, Gabon’s Republican Guards staged a military coup against the country’s newly “re-elected” leader, only a month after the Presidential Guards in Niger overthrew the elected government there and following three other coups in neighbouring countries, underlining a dangerous new trend on the continent.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 817

Israeli military raids Jenin refugee camp, killing civilians

‘Nowhere to go’: Rohingya face arson attacks in Myanmar’s Rakhine State

It is no coincidence that military-ruled Burkina Faso, Mali and Guinea declared their support for the coup in Niger (and now in Gabon). All three West African states have experienced putsches in recent years, reversing democratic gains that had seen the region briefly shed its tag as Africa’s “coup belt”. In the preceding years, a number of North African nations like Egypt, Sudan and Libya also suffered from military coups, which reversed hard-earned political gains.

Needless to say, military coups or generals meddling in civilian affairs are by no means recent or limited to Africa; they are ancient and global. Indeed, every continent has had its share of military interference at one point or another since Julius Caesar of ancient Rome.

But in recent decades, post-colonial states have suffered the most from military coups. There were hundreds, if not thousands, of such interventions, homegrown or instigated by imperial powers, across Latin America, Asia and the Middle East. In the quarter of a century after World War II, more than half of the world’s governments were overthrown by coups.

With the exception of a few major “breakthrough coups” that charted a new trajectory for their nations, such as the one in Egypt in 1952, most coups have proven senseless and costly. These were either “guardian coups”, which basically reoccur to maintain the status quo, such as the three military interventions in Turkey from 1960 to 1980, or the “veto coups”, which overthrow popularly elected governments, such as the bloody 1973 American-backed putsch against Salvador Allende’s government in Chile.

Most putschists promise heaven but deliver hell. And they often prove to be no less incompetent and even more corrupt and violent than their predecessors. This has been especially the case in the Middle East and North Africa, where putschists have learned how to hold onto power for decades with the help of loyal elite forces that they place at the top of their national army.

So if coups are fundamentally terrible, why do military officers continue to thrust their way into civilian life, at times with some fanfare, in Africa and other developing nations?

Well, there are five possible drivers:

First, because they can. According to experts, short of a revolution, only military officers have the capacity to stage a takeover of a state.

Second, because they feel they need to, as when the political leadership oversteps its authority, meddles in the military’s internal affairs or endangers national security.

Third, because they face autocrats who lack legitimacy or popularity to lead.

Fourth, because they secure support from at least one segment of the population that perceives them as national saviours, or at least a necessary evil, in times of deep national crisis.

And last, because they reckon they can act with impunity, thanks to regional complicity or international silence.

Yet such military rationale proves effective only when the sociopolitical situation is conducive to such dramatic changes in the government.

Corruption, poverty, mismanagement of state assets, political repression, deep polarisation and violent extremism are among the pervasive factors that render even democratically elected governments, such as the ones in Gabon and Niger, vulnerable to military coups. In such circumstances, large segments of the population lose all faith in democracy and their government, becoming ever more passive onlookers to the military’s actions.

On a deeper level, coups benefit from the absence of a liberal democratic tradition that upholds the rule of law, the separation of powers and the will of the people – one that trickles down to each and every citizen, including those in the military, making them recognise themselves as equal members of a state collective holding defined rights and responsibilities that transcend any other affiliations and loyalties – ethic, tribal, etc.

Ken Connor and David Hebditch conclude their sardonic and equally cynically titled book, How To Stage A Military Coup, From Planning to Execution, by listing 10 conditions that make a military coup likely: a country is a former colony or overseas possession; lies in tropical latitudes; has religious, ethnic and/or tribal divisions; possesses substantial natural resources, especially oil; suffers from endemic corruption and nepotism; is strategically located; has a long-term despotic regime; has army staff trained overseas; has financing available for mercenaries; and had a coup previously.

They seem to have a point – all the African states that have witnessed coups recently check most of the 10 boxes.

In sum, there is no easy remedy to prevent coups and stop military officers from meddling in civilian affairs, considering the long accumulative history of military interventions in civilian government. Imperial powers are to blame for long instigating military coups, but many of the recent coups were staged against Western, notably French imperial powers, which stand accused of robbing these nations of their natural resources and corrupting their leaders.

At the end of the day, a coup is “an inside job” par excellence, one that is enabled by the poor state of a state’s affairs. And the opposite is also true: a better, healthier, more transparent, inclusive and democratic state of affairs is the only way to prevent putsches and chart more equitable relationships with foreign powers.