Ramadan Mubarak, Guantanamo

As I mark my seventh Ramadan as a free man, I look back at the many holy months I spent in Guantanamo with mixed feelings.

Ramadan is a special time of year for Muslims around the world. It is a month that brings families, communities and entire countries together. For me, it was always a time of peace, spiritual dedication and reflection, and family bonding.

I remember fasting since I was a little child. My mother started training me when I was five years old, first having me complete half-day fasts. Then when I turned seven, I was able to do a full-day one, which earned me a lot of praise from family and friends.

As kids, we would stick out our tongues to each other to prove that we were fasting. A red tongue meant no fasting; a white and dry one, however, was a definite sign of it.

Most of the year my father worked abroad to provide for the family, and my mother was the one who raised and took care of us. In Ramadan, however, my father would come back to be with us.

We would start getting ready for iftar before sunset and my dad would sometimes cook the food. We would prepare special dishes, exchange food with other families and give it away to the poor. After dinner, we would go to the mosque to pray the nightly tarawih prayers.

We loved the special atmosphere Ramadan had and we all waited impatiently for this month to come each year.

In 2001, after I was sold to the CIA by local warlords in Afghanistan, I spent my 18th Ramadan in a black site – naked, blindfolded, and chained all day in a cold, dark cell under the ground. The American agents would blast loud music constantly and would only stop it when they would take me out for an interrogation. I didn’t – and couldn’t – know when Ramadan started, as I had no way to estimate the time of day.

I was given a “meal” every other day which basically involved soldiers pushing food and water into my mouth, feeding me “Meals Ready to Eat” (MREs). There was no going to the toilet, I defecated where I was chained. I lost so much weight that I passed out and I was given intravenous transfusions every few days.

Still, I wanted to observe Ramadan and decided that whenever they fed me, it was when I broke my fast. When I told the interrogators that I needed to fast because I thought the holy month had started, they mocked me.

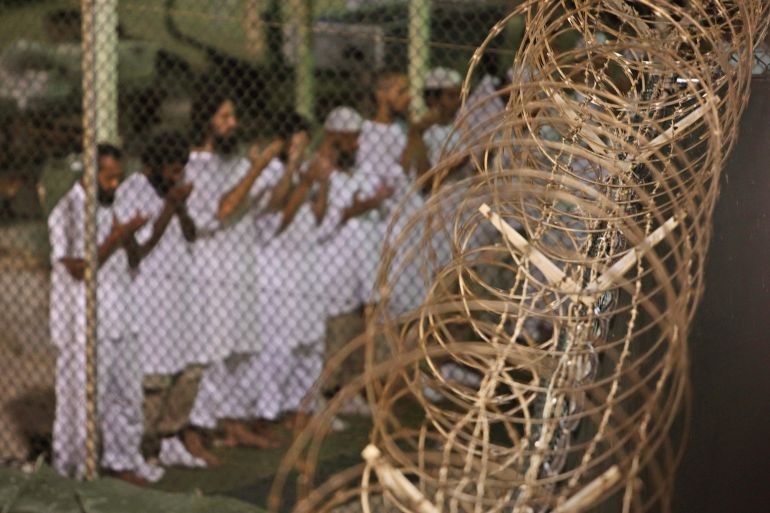

By the time my 19th Ramadan came, I had already been transferred to Guantanamo along with hundreds of other Muslims. We were quite a diverse group; some 50 nationalities were represented and 20 languages spoken.

We were so isolated that we didn’t realise it was Ramadan until the Muslim chaplain came and told us. It turned out we weren’t supposed to know the time and date, as it was a “matter of camp security and safety”.

“Ramadan Kareem, Ramadan Mubarak”, we congratulated each other in different languages. We all knew that Ramadan was going to be hard, given the living conditions in the camp.

The guards made it difficult to fast, serving food not before sunrise and after sunset – when we would start and break our fast – but when they decided to.

We would take the food and try to hide it so we could eat later, but the guards kept conducting cell searches and punished anyone who hid food by putting them in solitary confinement and depriving them of food.

So we decided simply to refuse to eat. We spent a few days not eating and asked them to bring the food on time, threatening to go on a collective hunger strike. After a few days, they gave us two meals, one before dawn and the second after sunset.

But then the guards started intentionally delaying our meals and would even steal from them. The MREs we were given were already meagre – we even called them “Meals that Refused to Exist” – and still they always took what they liked from them, usually the sweets.

We literally starved during this time.

When we tried to do a long nightly tarawih prayer, the guards didn’t let us. They told us we were allowed to pray only five times a day and could not pray collectively. While we stood to pray, they harassed and mocked us, and conducted cell searches. The guards knew that we can’t talk while praying, yet they considered this a refusal to respond and punished us for it.

If anyone didn’t respond, the guards would call the Immediate Reaction Force (IRF) team to forcibly extract a prisoner from his cell even while praying. Interrogations doubled during that Ramadan to intimidate us even more.

At one point, the interrogators started a new tactic to divide the prison population by offering to move prisoners to a quiet block if they cooperated with them. None of us bought into this; we stayed united and did things our own way.

Apart from the many challenges we faced during our first Ramadan in Guantanamo, we also spent the holy month thinking a lot about our families and homes, we missed them and missed observing Ramadan with them.

But we also realised that we had a new family – one big Guantanamo family. We talked about the different Ramadan traditions we had back home and the food we cooked. The beautiful memories we shared brought happiness and made us appreciate the holy month even more.

And so the Ramadans in detention rolled on, one after the other. We always prayed for freedom and justice, not only for ourselves but for everyone in the world who was unjustly imprisoned and oppressed.

When the holy month would come, we would sometimes be caged in solitary confinement. At other times we were in open cages where we could pass food to each other. When there was no food, or it was served too late, prisoners would share a single date or one apple or a slice of bread they managed to hide from the guards.

Sometimes the food would return to the person who first passed it on because each prisoner wanted his brother to eat first. Such moments filled my eyes with tears. Waddah, a Yemeni prisoner, was known to only eat one meal a day and would always send his meals to other prisoners, to those who starved. “I can’t bear seeing my brothers starve,” he told me. This tender man did not make it alive out of Guantanamo.

In 2006, we had one of the hardest holy months.

We were a year into our collective hunger strike, for which we were punished by being brutally force-fed. The camp administration had made rules even harsher and our living situation had worsened. The appointment of Lt Ron DeSantis – the present governor of Florida – as Judge Advocate General to supposedly ensure we are treated humanely did not make a difference

Three months before the start of Ramadan, three of our brothers – Yassir, Ali and Mana’i – died. The camp administration said they committed suicide; we knew they were lying. Two of them were approved to be released from Guantanamo; why would they take their own lives? While an official investigation by the US government maintained that the deaths were suicides, people who investigated the matter separately, including a former guard, suspected that our brothers were killed during torture.

That Ramadan, we fasted and prayed with broken hearts.

The following year, we spent the holy month in solitary confinement. The camp administration pressed on with brutal force-feeding but at least we managed to convince them to do it before dawn and after sunset to observe fasting times.

The situation continued like that till 2010, when the Obama administration decided to slightly improve our living conditions, having failed to close Guantanamo, America’s black hole. We negotiated with the camp administration to allow communal living in return for an end to the hunger strike.

That year we had one of our best Ramadans. I still remember the day it started – it was August 11, 2010. We had better food, refrigerators and microwaves, and our families and lawyers sent us spices and sweets. Prisoners from different countries cooked their dishes and shared them with everyone.

Each two blocks out of the six housing prisoners were allowed to be together during Ramadan, so we had a collective iftar every day. We shared our food with some guards and camp staff who liked it.

We were free to be together 24 hours a day so we could do all our prayers together. For the first time, we felt it was Ramadan, although we were away from our families. Some of the guards tried to fast too, we encouraged them and prepared special food for them.

During Ramadan in 2011, there was a Muslim navy guard who would always pray and fast with us. He would join us for iftar and we became very close friends. He contacted me this year and we said Ramadan Mubarak to each other.

As I mark my seventh Ramadan as a free man, I still think of my brothers, my big Guantanamo family, and the many holy months we spent together.

This Ramadan, 31 men are breaking their fasts in Guantanamo without their families, far away from their homes, having been imprisoned for more than two decades. Seventeen of them have been cleared for release.

We must not rest until all of them are free and are able to sit at the iftar table with their loved ones.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.