On the Ukrainian David, and the Russian Goliath

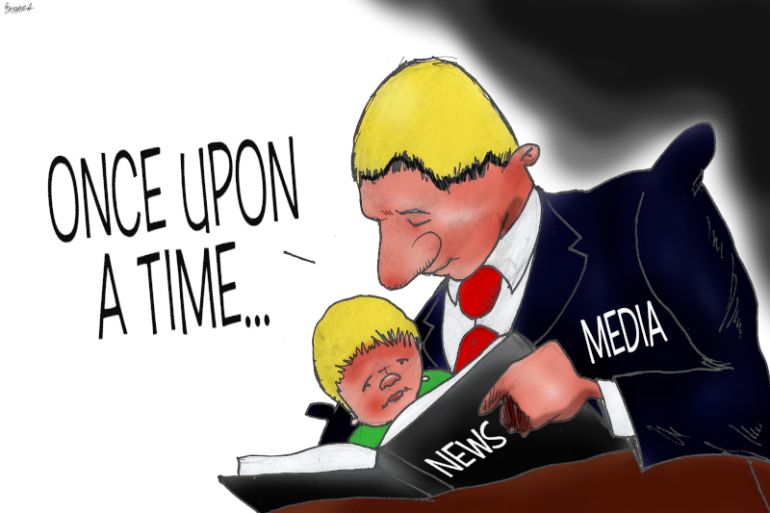

The media is working hard to sell us a black and white narrative on Europe’s latest war, in which small, brave and pure Ukraine is facing a big, evil and brutal Russia.

I have been wondering why the Western media’s 24-hour coverage of the ethnic conflict in Ukraine has left such a sour taste in the mouth. It is not just the racism of the reporters and the hypocrisy of the response to the awful humanitarian crisis the Russian invasion has provoked, though those are galling in themselves. I think it is more the tone of the coverage, how hard the narrative of the Ukrainian David – small, brave, pure – facing down the Russian Goliath – big, unwieldy, stupid and above all, evil and brutal – is being pushed. If there is one thing I have learned, it is that the world is rarely so black and white and to be suspicious when people try to present it that way.

The Russian state in many ways has made it easy. It makes for the perfect villain. A history of repression and mass murder at home and abroad, of backing tyranny, and jailing and assassinating dissidents makes it hard to empathise with. And in Vladimir Putin, the former KGB agent (which itself carries nefarious undertones, thanks to Hollywood), the villainy easily becomes personalised. On the other hand, there is Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the comedian who became president and is now the embodiment of Ukrainian (and by extension, Western) bravery and grit in the face of insurmountable odds.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 810

How significant is Russia’s new offensive in northeastern Ukraine?

Russia intensifies attacks on Ukraine’s Kharkiv region

It is not that I am not horrified and repulsed by the Russian invasion, and particularly by the horrendous impact it is having on ordinary people. It would be inhuman to fail to empathise with the suffering imposed on Ukrainians and people of other nationalities. In fact, that should go without saying. But that we are compelled to state so unambiguously or risk being branded Kremlin apparatchiks, speaks to the enforced compliance with the single, simplified story of good vs evil. It is a story that will not countenance complexity. The Russians cannot have any legitimate grievance (even when one disagrees with their gruesome methods) and the Ukrainians’ faults are either airbrushed out or minimised.

Thus, the media does not dwell too much on the many warnings about what the expansion of NATO would unleash. Neither is too much ink spilt on the systemic racism displayed by the Ukrainian state which, even in its hour of dire need, has problems acknowledging the humanity of non-Europeans. When not dismissed out of hand, the complaints by foreign students are given short shrift in the media. Similarly, while denouncing the distortions of truth and lies in the Russian state press, Western media seems happy to excuse similar distortions and lies from Ukraine’s media-savvy government. Violations of the laws of war by Russians are condemned while justifications are sought for Ukrainian videos of Russian PoWs and for images of children being trained to fight.

The establishment and enforcement of a single media narrative from which any departure is strongly discouraged is, of course, nothing new. During the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, which was just as objectionable and bloody as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, reporter Peter Arnett was fired for “grant[ing] an interview to state-controlled Iraqi TV, especially at a time of war,” and “discuss[ing] his personal observations and opinions in that interview.” As reported in The Guardian, Arnett had said in the interview that his Iraqi friends told him there was a growing sense of nationalism and resistance in response to the “nauseating” actions of the American and British invaders. Sound familiar?

The world is a complex place. Just because a people are victims of a horrible crime does not mean they cannot themselves do terrible things. By erasing the complexity and trying to replace it with a tale of pure Ukrainians and debased Russians, Western media is creating what Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie famously called “the single story”. Power, she says, is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of them. “Show a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become”.

The problem with a single story is not that it is necessarily false. Many of the media reports coming out of Ukraine are true. However, they ignore complexity and doing that distorts rather than explains the world, its conflicts and its contradictions. The media’s attempts to establish a single story of the conflict are about power, not truth. That’s why I find the coverage so disturbing. The reports are not news. They are morality tales posing as the news.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.