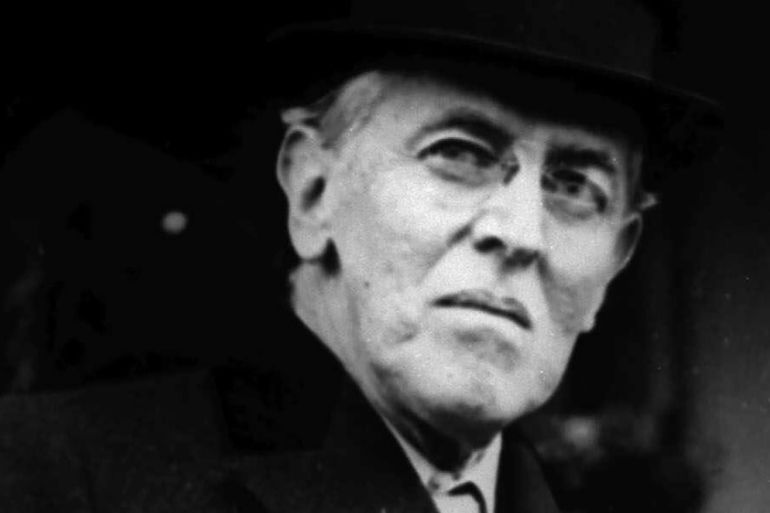

Woodrow Wilson’s racist legacy and decolonising modern sanctions

Wilson was not only an avowed racist, but also an architect of a sanctions regime that continues to kill to this day.

A Nobel Peace prize holder usually remembered for his idealism, Woodrow Wilson, president of the US from 1913 to 1921, supported segregationist policies at home and played a key role in defeating a Japanese proposal to write the principle of racial equality into the Covenant of the League of Nations. His views on race stemmed from a deeper belief in white supremacy as a guarantee of peace, order and stability.

Already in 2015, the Black Justice League, an activist student organisation, occupied the office of the Princeton University’s president, demanding that the Ivy League institution recognise Wilson’s “racist legacy” and remove his name from all university premises. Princeton refused to budge, citing Wilson’s important contribution to the university.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBiden labels Japan and India ‘xenophobic’ along with China and Russia

After deadly attack, Russia’s Central Asian workers report rising racism

‘Feel less and less like playing’: Vinicius Jr in tears over racist abuse

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the massive anti-racist mobilisations that followed, the university recently announced that it will remove Wilson’s name from its School of Public and International Affairs. That battle was finally won.

Modern sanctions

Another battle, however, awaits to be fought. Less known is that President Wilson was also one of the architects of modern sanctions, packaging them as peaceful alternatives to war. Upon returning from the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, he addressed an Indianapolis crowd with enthusiasm about the new system of sanctions that would guarantee peace. Without recourse to armed force, he said, the League of Nations would be able to “Apply this economic, peaceful, silent, deadly [and] terrible remedy. It does not cost a life outside the nation boycotted but it brings a pressure upon the nation which, in my judgment, no modern nation could resist.”

There always was a degree of irony in Wilson’s juxtaposition of peace and death. Be that as it may, history would soon prove him wrong. Not only did sanctions fail when applied to powerful states or did little to avert the second world war, but over the last three decades, their increased popularity, itself the product of their allegedly peaceful character, has cost an unprecedented number of lives. Half a million children are said to have died as a result of UN sanctions against Iraq in the 1990s, and more than 40,000 civilians due to US sanctions against Venezuela today.

More generally, sanctions do not only isolate their target but frequently set the clock back on industrial, socio-economic and political progress with disastrous effects on the social fabric and the prospects of long-term reconstruction. Israel’s longstanding siege on Gaza is a case in point.

Transnational civil society campaigns have consistently rejected efforts to cast sanctions as peaceful, and have mobilised the language of war and violence to call for their abolition: sanctions do kill, and in the context of a global pandemic, the effects of the lack of adequate medical supplies can be a death sentence and are unlikely to stop at the national border.

Imperial legacies

Wilson’s legacy, however, should also prompt us to ask to what extent was the concept of “peaceful sanctions” tied to the racist colonial order of the 19th and early 20th centuries? And how is the current proliferation of sanctions linked to the persistence and deepening of racialised imperial structures in the present?

Peaceful sanctions adopted outside a formal state of war, from so-called “pacific blockades” to embargoes, became a routine practice among colonial powers in the 19th century. These sanctions were not limited to the enforcement of international obligations or the pursuit of foreign policy objectives but were also adopted to collect debt, enforce private contracts and secure compensation for injury to their nationals. All served the same cause: to advance imperial ambitions without assuming the risks and responsibilities of war. With the establishment of the League of Nations, multilateral sanctions became part of an international arsenal used to effectively preserve the colonial status quo.

The imperial chain was not broken with the foundation of the United Nations. The Security Council’s power to impose sanctions in response to threats to peace was seen as a mechanism for policing weaker states. After decades of inactivity during the Cold War, it would be deployed to restore order in post-colonial societies, particularly in Africa, and to punish states defying the values and norms of the “new world order”, such as North Korea.

In today’s globalised capitalist system characterised by market dependency, unequal structures of production and exchange, and the dominance of the US dollar, sanctions have also proven a strategy of choice for the US and its allies.

The link between Wilson’s legacy of “peaceful sanctions” and his legacy of racism and imperialism are, therefore, difficult to ignore. One needs only to take a look at the cartography of sanctions to see clear parallels with the geography of the colonial era.

If his legacy has anything to teach us, it is that calls for the abolition of sanctions should not only be tied to a humanitarian agenda concerned with minimising human suffering, but to a decolonising project which understands the inhumanity of sanctions as a constitutive feature and symptom of imperial ordering.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.