Coronavirus is an impetus to decarcerate America

The pandemic, and its increasing human toll, have finally started a conversation in the US about mass imprisonment.

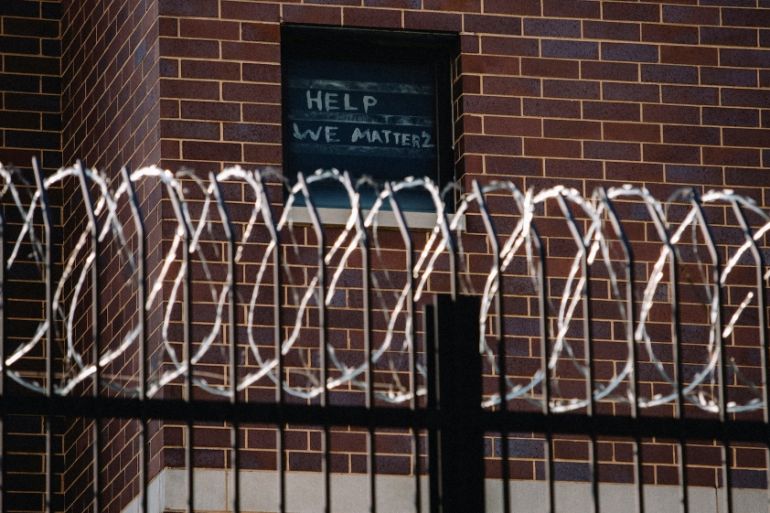

The novel coronavirus pandemic, which has already killed more than 60,000 Americans, is forcing the United States to come to terms with the deplorable state of its jails, prisons and detention centres.

The rapid spread of COVID-19 across the US led to fears that the country’s overcrowded and unhygienic correctional facilities, where social distancing is impossible, could act as incubators of the disease. Experts calculated that poorly and inhumanely managed prisons could add 100,000 extra deaths to the coronavirus death toll in the US. Meanwhile, a New York Times investigation revealed that more than 23,000 inmates and staff members in US prisons and jails already tested positive for coronavirus, demonstrating that America’s correctional facilities are at the ground zero of this outbreak.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsFamily says al-Shifa doctor was tortured to death in Israeli prison

The Abu Ghraib case is an important milestone for justice

More than 100 inmates escape from Nigeria prison after heavy rains

As a result, following the lead of other countries, authorities in many US states started to release prisoners in an attempt to stem the spread of the virus.

These releases, however, are not happening quickly enough to protect America’s imprisoned masses, and everyone else living in the communities that they belong to, from this disease. The nation is now faced with the realisation that it should not have put so many people behind bars in the first place and that mass imprisonment is not only a major human rights violation, but also a threat to public health.

Activists across the country are calling for comprehensive criminal justice reform not only to stop the spread of the virus now but also to prevent the country from once again finding itself in such a disastrous situation in the future.

In Philadelphia, where advocates unsuccessfully petitioned the state supreme court to release children from juvenile facilities during the pandemic, not only activists but also members of the justice system are calling for reforms. US District Judge Anita Brody, for example, referred to prisons as “tinderboxes for infectious disease” when granting compassionate release to a prisoner. Moreover, the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office, the Defender Association of Philadelphia and the ACLU of Pennsylvania are working in concert to decarcerate to stop the spread of the virus. Police in the state, meanwhile, is “delaying” arrests for certain low-level offences.

In California, where some prisoners complained that they feel like they are in a Nazi death camp, Governor Gavin Newsom called for the expedited release and parole of 3,500 people. The comparison prisoners made was apt, given that many Holocaust victims died not in gas chambers but of infectious diseases. Anne Frank, for example, died of typhus.

Indeed, the relationship between mass imprisonment and disease is an old one, and there is nothing “novel” about the carnage the novel coronavirus is currently causing in US prisons. Throughout the continent’s colonisation, many Native Americans died from unfamiliar diseases brought to their communities by their European oppressors. At least two million Africans died in slave ships during the Middle Passage to America, many succumbing to infectious disease and malnourishment.

Throughout slavery, the convict leasing system of Jim Crow-era segregation, and the current period of mass imprisonment and prison profiteering, negligence towards the health of the captive population has been built into the business model.

Conditions in US prisons are ripe for disease outbreaks. Correctional facilities across the country are full of older inmates from low-income communities that have limited access to healthcare. Moreover, many of these prisoners suffer from pre-existing conditions, such as respiratory problems and heart conditions, that make them more susceptible to infectious diseases. Indeed, there are studies that show American prisoners have an elevated risk of contracting infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, hepatitis B and C, HIV/AIDS, MRSA and now COVID-19. Of more than 10 million imprisoned people in the US, 4 percent have HIV, 15 percent have hepatitis C, and 3 percent have active tuberculosis.

Although prisoners have a constitutional right to health care through the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of “cruel and unusual” punishment, the care that is on offer in many US prisons is either limited, or worse, nonexistent thanks to high drug prices and the prison managers’ reluctance to reduce profit margins.

Take hepatitis C. Nationwide, roughly 97 percent of inmates with hepatitis C do not receive treatment for this curable liver disease, as drugs can cost on average about $90,000 for a course of treatment. Lock-up is expensive. If all inmates who have hepatitis C received treatment, the costs would far exceed the minimal budgets prisons put aside for healthcare, making the “business” of imprisonment completely unprofitable.

The lack of healthcare in correctional facilities is a threat not only for the imprisoned populations but for the wider society. Many inmates re-enter society at the end of their sentences with untreated health conditions. As former offenders often experience financial hardship, they do not receive treatment outside the prison either. As a result, they contribute to the spread of infectious diseases in their communities. Roughly 640,000 inmates are released nationwide each year. This means, about 75,000 hepatitis C-infected people enter the general population annually.

The lack of healthcare in US prisons, which causes former offenders to unintentionally become vectors of infection, poses a greater threat to society today than ever before. Many former offenders, who did not get tested for coronavirus during their incarceration, risk unknowingly infecting their loved ones and contributing to the spread of the disease once they rejoin society.

Today, American prisons and jails are one of the epicentres of the coronavirus pandemic. While the release of an increasing number of inmates to stem the spread of the infection is a step in the right direction, it is just a partial, short term solution. Until America shakes off its addiction to mass imprisonment, reforms its brutal sentencing regimes, ends over-policing and starts to offer adequate healthcare to imprisoned populations, correctional facilities in the US will continue to be costly hot spots for infections.

Confinement has always been dangerous, and deadly, in the US. For too long, the most vulnerable and underprivileged members of the American society, particularly those who are descendants of slaves and frequent victims of state violence, and those who are most susceptible to the negative effects of poverty, pollution and unemployment, have been unjustly locked up in inhumane conditions.

Many Americans have long been ignoring this depressing reality, and buying into “get-tough-on-crime” policies promoted by politicians on all sides of the political spectrum. The continuing pandemic, and its increasing human toll, however, have finally started a conversation in the country about the need for and the effectiveness of mass imprisonment. This conversation should not end once we defeat this deadly disease. The US must learn some lessons from its obvious failure to respond effectively to this pandemic. It must rapidly implement decarceration policies and start offering adequate healthcare to its confined population, for the sake of all Americans.

The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.