Can Eritrea’s government survive the coronavirus?

Eritrea’s failure to efficiently respond to the pandemic could bring down its authoritarian government.

The majority of political leaders across the world responded to the continuing coronavirus pandemic, which has already killed more than 190,000 globally, by calling for increased international cooperation and welcoming any financial, medical and humanitarian aid that is offered to them by foreign entities to help protect their constituents. This is why New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo happily accepted China’s proposal to send 1,000 ventilators to his state, and Italy gratefully welcomed hundreds of Cuban doctors who offered their help in the country’s fight against COVID-19.

Similarly, when the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba’s founder Jack Ma offered to send hundreds of ventilators as well as hundreds of thousands of personal protective equipment (PPE) to 54 countries in Africa, most African leaders, such as Ethiopia’s Abiy Ahmed and Rwanda’s Paul Kagame, swiftly accepted the donation and expressed their gratitude.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMexico’s teachers seek relief from pandemic-era spike in school robberies

‘A bad chapter’: Tracing the origins of Ecuador’s rise in gang violence

Why is the US economy so resilient?

The leaders of Eritrea, a country ranked 182/189 in the United Nations’s 2019 Human Development Index, however, surprisingly chose to reject the vital equipment Ma offered to send them. On April 5, the head of Economic Affairs for Eritrea’s ruling People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) party, Hagos “Kisha” Gebrehiwet, publicly confirmed that the Eritrean government rejected Ma’s donation. Talking as a guest speaker at the bi-weekly Hagerawi Nikhat (“national consciousness”) teleconference, an exclusive online seminar in which senior party officials get a chance to communicate with their cadres in the diaspora, the man in charge of Eritrea’s economy said the country does not want to become a “dumping site” for “unsolicited donations”. Accepting such offers would be against “the principled stance of the Eritrean government which advocates for self-reliance,” he added.

Within the very same online seminar, Gebrehiwet explained that the Eritrean leadership is now trying to buy the medical equipment needed to treat COVID-19 cases from the incredibly competitive Chinese market and arrange the shipment of these items to Eritrea on chartered planes.

Of course, despite its rejection of foreign aid, the Eritrean government does not have the necessary funds to swiftly make such purchases. As a result, it turned to its own long-suffering citizens and launched aggressive fundraising campaigns to make them donate the little money they have to the state to help the efforts to combat the virus. Thanks to these aggressive campaigns, some of Eritrea’s most penurious citizens, including members of the national service, have already been coerced to make donations. It is not yet known, however, whether these donations proved sufficient for the country to buy everything it needs to contain the spread of the virus.

While the Eritrean government undoubtedly hindered the country’s ability to respond to this public health emergency by rejecting Ma’s generous donation, this was only one example demonstrating its tendency to value its own image and survival more than the wellbeing of its constituents, even during a pandemic.

While Eritrea is one of the most isolated countries in the world, it did not escape the pandemic. The first COVID-19 case in Eritrea was reported on March 21, and, as of April 28, there are 39 confirmed cases in the country, of which 19 have recovered according to the Ministry of Health. The country has been in a nation-wide lockdown to slow the transmission of the virus since April 1.

The pandemic has not yet reached its peak in Eritrea, but all signs indicate that the country is heading for catastrophe.

Eritrea’s healthcare system is not strong enough to handle a deadly and highly infectious disease like COVID-19. Even before the pandemic, the country’s healthcare facilities had been suffering from an acute shortage of supplies. At certain times, patients have even been asked to buy intravenous (IV) infusions from private pharmacies before being admitted to hospital. The Eritrean government closed all private clinics in 2009. In the second wave of state seizure that started in June 2019, it also took control of 29 Catholic hospitals, health centres and clinics. Meanwhile, the unfavourable working conditions pushed many Eritrean physicians to flee the country, causing major staff shortages in hospitals.

And lack of quality public healthcare is not the only reason why the coronavirus pandemic is likely to have catastrophic consequences for Eritrea.

Although many countries, including some developed nations, are suffering from a shortage of essential products as a result of the pandemic, the magnitude of the problem is double in the case of Eritrea where import and export businesses have been banned since 2003.

As, even during normal times, Eritreans can only buy rationed essential supplies that are on sale in the governing party’s stores, they could not stockpile to prepare for the lockdown. Moreover, even if the state miraculously managed to secure extra goods to put on sale, Eritreans would not be able to do any extra shopping as they are not allowed to withdraw more than $330 in any given month from their own savings. This, despite Eritrea being a complete cash economy.

Since the mid-2000s, Eritrea’s President Isaias Afwerki has been spending most of his time supervising dam constructions. Yet the country’s major cities, including the capital, are still suffering from a chronic shortage of running water and electricity. In August 2018, the regime rounded up many water-tank truck owners. Many of them remain in prison. All water bottling companies were closed in June 2019. This makes it impossible for many Eritreans to follow the hygiene protocols necessary to curb the spread of the virus.

If not impossible, the regime has also made it very difficult for Eritreans in diaspora to help their family members back home. Eritrean citizens living abroad are required to pay the so called “diaspora tax” first if they want to send goods to their home country. Wiring money back to Eritrea is also not easy for members of the diaspora, as they are forced to use an extremely deflated fixed currency rate imposed by the government to do so.

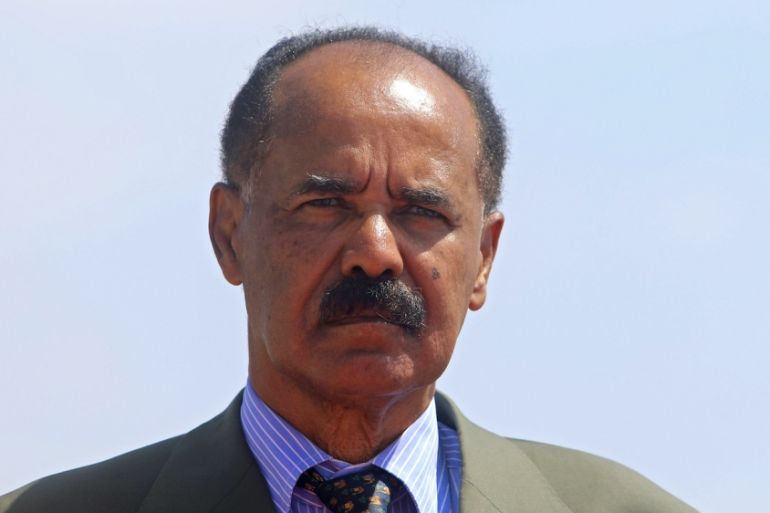

Eritreans are also suffering from a lack of political leadership during this difficult time. While the leaders of most countries are doing daily briefings to inform their citizens on the latest developments about the pandemic, President Isaias has not spoken to the Eritrean people or media for almost two months after giving an interview to the state-run media in mid-February, in which he did not even mention the growing threat posed by the new coronavirus. His prolonged absence from public life led to rumours that he is incapacitated or even dead.

Inside sources told me the president was in the port-city of Massawa during his months of absence from public life, as he reportedly plans to relocate his temporary office to Gedem, near Massawa. Sources close to the matter also told me that it has been very difficult to get hold of him during this time. In an extremely centralised system, where senior state officials cannot make the smallest decision without the president’s approval, one can only imagine the damage caused by Afwerki’s absence during such a crucial time.

After his prolonged absence, on April 18, the president suddenly sent a five-minute recorded message to the Eritrean people from an unknown location. Afwerki only mentioned the pandemic in the introduction of his message and went on to tell his constituents that COVID-19 should not “derail the development programmes” his leadership has embarked on. The president’s message made it clear that the pandemic is just a secondary concern for the government. The Ministry of Information, however, only translated into English the short section of the message where the president mentioned the pandemic.

As it became clear that Eritrea is not going to be able to protect its citizens from COVID-19, rights groups, exiled scholars, and the UN’s Special Rapporteur on the situation of Human Rights in Eritrea, have called on the Eritrean government to release the tens of thousands of prisoners of conscience who have long been languishing in overcrowded and unsanitary prisons. Many also expressed concern about the thousands of students who are living in cramped conditions at the Sawa military training centre.

During his online seminar, Gebrehiwet also responded to these calls, brushing them off as “hypocritical”. Rather than offering an explanation as to how they are planning to stop the virus from spreading like wildfire in prisons and military schools, he claimed these would be the best places for anyone who needs to be in quarantine.

In response to the growing criticism of its COVID-19 response and concerns over the wellbeing of its citizens, the Eritrean government issued a statement on April 6, accusing the UNHRC of “harassment” and claiming that the state’s “enemies” are using the pandemic to push for regime change.

While the accusation that rights groups, media organisations and the UN itself are using the pandemic to push for regime change in Eritrea is clearly unfounded, there is a very real chance that this public health emergency is going to spell trouble for Eritrea’s authoritarian government.

History shows that public health crises such as pandemics, food shortages or extreme pollution harm all governments, but pose the most significant threat to authoritarian regimes. The 1973-1975 Ethiopian famine, for example, was the final trigger that ended Emperor Haile Selassie’s reign in the country. In Sudan, it was Omar al-Bashir’s repeated failure to handle such crises, such as the cholera outbreak of 2017 and the spike in the price of bread in 2018, that led to the demise of his 30-year regime.

The Eritrean government demonstrably failed to respond efficiently to the most significant public health threat the world has faced in a century. If it does not change its ways, accept the global community’s help and take action to save the lives of already-suffering Eritreans, it is unlikely to survive past this pandemic.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.