Who gets to picture and narrate Africa?

African photographers are still struggling with exclusion and marginalisation by major press organisations.

The World Press Photo Foundation recently announced the participants selected for the 2018 Joop Swart Masterclass. It is the foundation’s flagship education programme that “rewards the most talented emerging visual journalists and is designed to support and enhance diversity in visual journalism and storytelling”.

This year, far more women were selected, and that alone must be commended in a field that routinely overlooks women. Although the immensely talented Leonard Pongo, who is Belgian, but of Congolese descent, was one of the selected photographers; African-born, Africa-based photographers – male or female – were notably absent.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWall Street Journal cuts Hong Kong staff, shifts focus to Singapore

Abu Dhabi-backed group ends bid to take over Telegraph newspaper

Two Russian journalists arrested over alleged work for Navalny group

Why is this lack of representation from African countries so important?

Gifted and experienced photographers from the continent continue to be marginalised. Lack of recognition by powerful organisations like World Press Photo (WPP) and Magnum means that photographers lose out on opportunities to enhance their technical ability and network with each other and commissioning editors.

It is important to note that photographers from African countries often do not even make it to the list of nominees for competitions, because the nominators themselves are based in localities that do not give them knowledge of the existence of these photographers.

By choosing who gets to be recognised, selected for training by respected photographers and photo editors, and networked into powerful media houses, such organisations have the power to direct who pictures and narrates our world. More importantly, they get to choose who photographs and narrates the experiences of those who the geopolitical west has seen as “other”.

Inevitably, by leaving out photographers from African countries, and continuing to skew the selection process towards photographers who are from Europe and North America, the way the world pictures and imagines Africa and Africans will remain as they have historically been framed by the geopolitical west – as location of a special brand of savagery and darkness to which those in the west have no parallel experiencesor equivalent.

Last year, in an article for Al Jazeera English, titled The problem of photojournalism in Africa, I wrote a response to the New York Times’ use of troubling photographs of African refugees and migrants, as well as the larger issues surrounding the way in which photojournalists pictured Africa and Africans in deeply problematic ways. In the article, I discussed how the main reason for photojournalists’ depictions of Africans in caricatured ways was the reluctance by powerful news organisations based in the geo-political west to employ African and locally-based photographers.

In subsequent conversations, many photographers have said that African photographers, too, might feel pressured to produce certain stereotypical narratives; media houses expect and pay for caricatured, “easy-to-read” images.

Despite the pressure to get photographs that reflect simplistic notions of “tribal” conflict, savagery, disease and general darkness that reflect the geopolitical west’s expectations for “Africa”, a local photographer would almost certainly produce more nuanced narratives than a parachuted-in photographer who has little to no knowledge of a given situation.

Corporate cover-up

World Press Photo was founded in 1955 by a group of Dutch photographers, who organised an international contest as a way of creating global recognition for excellence. Its annual competition and prize is seen as the pinnacle of achievement in photojournalism, with a worldwide exhibition programmegiving the winner the opportunity to show their work in 45 countries to an audience of some 4 million people, according to WPP. Most of these locations happen to be in Europe, and none are in Africa.

Prince Constantijn of the Netherlands is the patron of the organisation which is financed through sponsorship from the Dutch Postcode Lottery and Canon, as well as partnerships with other supporters and contributors, including the Associated Press, ING Bank, and WeTransfer.

The power of this patronage and income allows WPP’s managing director Lars Boering and his 27 staff members to promote, according to its mission statement, “high-quality visual stories, we create and support the conditions that make possible the stories that matter.”

But those powerful networks of patronage and income do not seem to have figured out a way of meeting their goals of “transparency” and “diversity” when it comes including photographers from Africa in its prestigious training programme.

Although just over 20 photographers from Africa were nominated within the pool of 219 total nominees, eight photographers made the nominee list from Egypt, and two from Morocco – areas of the continent that are networked with Arab geopolitics in far different ways from other parts of what is (problematically) called “Sub-Saharan” Africa.

Three of the nominees are from South Africa, two from Nigeria, and one photographer each from a scattering of other African countries. Of the three South Africans, only Nocebo Bucibois a black photographer; the other two are white.

In a country with South Africa’s racial dynamics, which continues to offer far more opportunities to those who are white, it is (laughably) not uncommon to hear grumbling about black artists and photographers getting opportunities over those who are white in closed conversation circles.

Yet of the large young, talented black photographers who are making their way, the South African nominators only found one black person to nominate. Perhaps not many black photographers applied.

If that is the case, is it not part of the mandate of WPP’s on-the-ground people and nominators to cultivate less-represented photographers’ portfolios for presentation?

On Twitter and Facebook, photographers expressed their ire. It was obvious that despite good intentions, the cycle of exclusion continues, and the excuses continue. Andile Buka noted, wryly:

https://twitter.com/Andile_Buka/status/985779834864488448?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

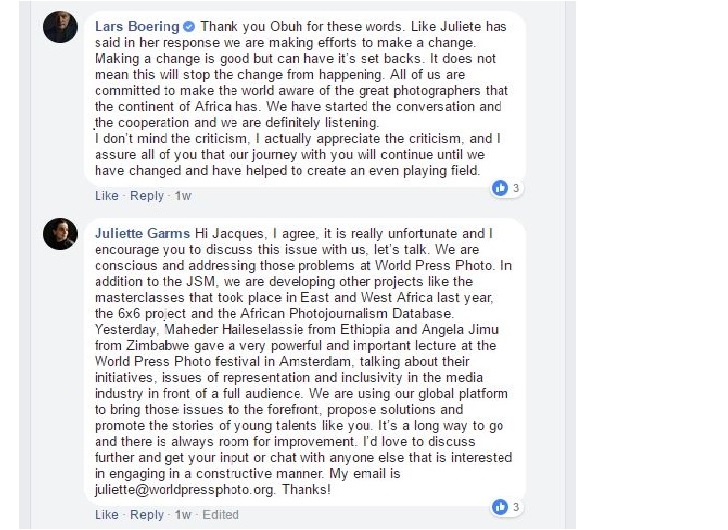

When Jack Yakubu Nkinzingabo – a Rwandan photographer and founder of Kigali Center for Photography – expressed his disappointment in a Facebook post, the responses from WPP’s managing director Boering and education programme coordinator Juliette Garms were predictable:

To be honest, I laughed when I saw these responses. Black and brown people (and women, and anyone from a group that’s been systematically excluded) will only recognise all this rhetoric too well. What is there to “discuss” at this stage?

No one who is “conscious and addressing those problems” would leave such glaring gaps in who exactly is chosen to nominate, where they are located, what their (national, racial and gender) positionalities are, and where the nominees come from. We are not a gender and colour-blind world. “Those problems” to which Garms so delicately alludes – conveniently without naming them – are built on structural racism and personal prejudices.

WPP’s selection process reflects exclusionary practices – created by such tired, old, obvious ways of privileging certain groups and erasing the presence of a specific “other” that’s historically been excluded for the same exact reasons. “Discussion” has been on-going, apparently without much result, for decades. If one has to still “discuss” the obvious, I can only laugh.

Garms’ and Boering’s rhetoric are almost stereotypical examples of corporate evasion and cover-up. Their practices leave those employed as “tokens” in a terrible position (case in point – the anecdote Garms puts forward to “prove” WPP is making an effort).

Those who are thus tokenised are aware of their predicament. They realise that refusing to partake robs them of an invaluable opportunity to make headway in an industry that rarely opens doors for black people from Africa, and for women.

Photographers also know that if they directly confront a powerful organisation like WPP, they will be further marginalised, marked “troublemaker”, and not invited even as a token.

African photographers speak up

Of the many people who responded to my own criticism of the WPP’s choices for the Joop Swart Masterclass, which I posted on Facebook, it was mostly African diasporic photographers who operate outside Africa – who have more opportunities to network – as well as those photographers who already have well-established careers, who felt comfortable enough to make public statements.

Cedric Nunn, a South African photographer with a long and distinguished career, remembered that he attempted to address the issue of exclusion of African photographers by WPP about 20 years ago, as then director of Market Photo Workshop.

“I was not afforded the dignity of a response … I think they just didn’t give a damn what anyone said in the colonies, and now they have to make some polite mumbles.”

Like others with whom I discussed this latest instance of exclusion, Nunn, too, said, “We came to the conclusion that we needed our own standards and institutions that would have a different set of values attached, and depart from the sensationalistic images” that agencies based in the geopolitical west preferred, and sometimes demanded.

French-Ivorian photo editor Anna-Alix Koffi, who served as a nominator for the Joop Swart Masterclass in previous years and as a judge this year, notes that the process is fraught to begin with.

Though there were many Egyptian photographers nominated, few from other parts of Africa were nominated, she pointed out. And judges – inevitably – bring unconscious biases to the table, unless they have been immersed in processes of addressing and countering their existing prejudices.

Last year, when Koffi was part of judging the Masterclass in West Africa, she pointed out that African photographers dealt with enormous obstacles, such as lack of finance and mobility. For many African passport-holders it is nearly impossible to obtain visas to travel within Africa and outside Africa.

But her honest comment had been met with scepticism, and her statement was scrubbed and shaped into a neat, generic “thank you WPP” message.

Koffi concluded:

“It’s a very good thing that a major and prestigious organisation such as WPP are interested in creating opportunities for photographers from Africa. […] But it’s a long process that requires more involvement from more organisations. At the moment, however, ‘Africa’ is like a piece of soap in western hands – they don’t really know how to handle it.”

It’s too complex to do it from the outside. There are surely good intentions, but what they really need are people who are there, imbedded into photographers’ networks, who understand the local gender and class dynamics, and even racial or ethnic group dynamics of the locale. There are African specialists from the field that they can hire. In the case of WPP, they should have an office in Africa with locals to make sure it’s genuine and long-term success.

A myriad of other structures – including prizes – maintain photographing Africa a game for white, European photographers, most of whom continue to re-imagine and re-present it exactly as their cultural history has trained them to do.

Toronto-based Liz Ikiriko, an independent curator and photo editor concurred. “WPP has learned the language of co-opting without creating any significant and long-lasting opportunities for African photographers. Those practices are also reflected in other, smaller competitions.”

As a member of the jury for the Contemporary African Photography prize (run by Ben Fuglister in Berlin), she also realised that problematic dynamics are inherent to the selection process, which resulted in very few African-born photographers being included.

“I was shocked to realise that there was no way of identifying African and/or Diasporic submissions. That was not a requirement and of course, because [Fugulister’s] circles are mostly European, the submissions are 80% from white European photographers who shoot in Africa. I spent considerable time [trying to] identify African photographers and prioritising their contributions in my voting. I’m happy to see that a few of them were shortlisted but of course there are many Europeans in the shortlist.”

Because this prize is framed as “a photography prize not a photographer prize” it means that well-meaning efforts to imagine the playing field as equal yields few photographers who are actually African. Instead, it is slated to reward, once again, Europeans who fly into Africa to photograph locations with which they are not familiar, often through the same, unquestioned and stereotypical lens.

As one photographer who wished to remain anonymous said:

“There is a difference between good intentions and real actions that create space for those we’ve historically and actively marginalised. We’ve seen plenty of well-intentioned initiatives, but if they are not making headway, WPP and others need to recognise that they may not actually be doing anything but making themselves feel better.”

It remains important to critique the prejudices and myopia of so-called “international prizes” (that really privilege Europeans and North Americans), training programmes, and photographers’ agencies.

But it is also important, as Koffi and Nunn suggested, to have African-built spaces and organisations to promote local photographers and operate with a different set of values and outlook.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.