Camp Zaatari, Syrians, and a new cosmopolis

Zaatari Camp is a microcosm of how Syrians are going back to point zero of their history, to reimagine it anew.

Topping the mid-August news was the horrific footage “shot by an independent journalist for Britain’s ITV News” that “appears to show victims of an alleged chemical attack that activists said killed hundreds of people” in Syria. In his assessment of this latest round of carnage in Syria, Marwan Bishara concludes, “Judging from their initial statements, I doubt the horrific death of another thousand civilians has fundamentally changed the position of those who’ve been either complicit or indifferent to the killing of one hundred thousand Syrians.”

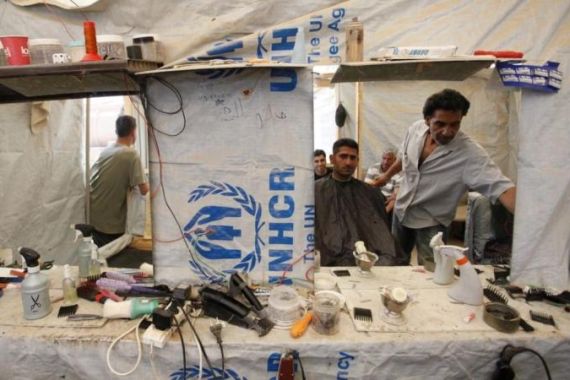

Under these circumstances it is neither surprising nor comforting to learn that “one million children have fled Syria conflict: Half of all who fled civil war are children and many under age of 11, joint UNHCR and UNICEF report says”. What is to become of these children? Known and unknown refugee camps are awaiting them. Let’s visit one such camp, through the lens of one particularly caring artist.

Art in the time of trouble

Mario Rizzi is an Italian photographer, filmmaker, and video installation artist who is now based in Berlin. For more than a decade, he has done some extraordinary work. Born and raised in Italy, Rizzi studied classics and psychology before turning his attention to photography at Ecole de la Photographie, Arles, France and the Slade School of Fine Arts, London, UK (for more on his art see his website here).

A quick look at his career shows his deeply caring and vastly cultivated camera work. Rizzi has a soft touch in his videography, his camera imperceptivity attending his subject with minimum of intrusion.

|

|

| Life inside Jordan’s Zaatari refugee camp |

An accomplished, widely exhibited, and respected artist in his field, Rizzi has committed his art to investigating the consequences of globalised neo-liberalism on human life in its simplest and most immediate meanings. He patiently and judiciously attends to the daily lives of people he films, and through their stories teaches us otherwise hidden consequences of the grand narratives of our history.

Mario Rizzi’s “Al Intithar” (“Waiting”), made on and about the Syrian refuge camp Zaatari in Jordan, is the first in a projected trilogy “Bayt/House”, reflecting on the emergence of a new civic imagination as to how, as he puts it, “the narration of a revolutionary event can be closely entangled with the narration of simple everyday events in the lives of unknown people”. He says:

“I worked several times in the Muslim world, mainly in Palestine and in Turkey, exploring the relationship between privacy and civil engagement and considering the notions of border and inequality, particularly in relation to issues of identity and presence.”

Camp Zaatari

The Syrian refugee camp Zaatari lies seven kilometres to the south of the Syrian border inside Jordan. As Mario Rizzi reports at the time of his filming, “There are already 45,000 refugees living here, and still more people arrive: 10,000 additional refugees every week. The capacity of the camp is 70.000 people. Many Syrians would like to go home: living conditions in the camp are by no means easy and they are often far away from their husbands and sons, many of whom have stayed behind to fight.” At the writing of this essay the total number of Syrian refuges outside their homeland has swollen to more than a million.

Rizzi opts to personalise the politics of the despair he sees:

“The film’s protagonist is a widow from Homs whose husband was killed in an attack by the Syrian army. Director Mario Rizzi followed this widow’s life at the camp for seven weeks. Life’s rhythms are dictated by the place, and life here is all about waiting.”

How does Camp Zaatari compare with other camps in history, and how are we to understand the lives of the Syrians now living there? As Rizzi’s camera guides us through the camp, we see how “the bared life” of Syrians is “the state of exception” (as the Italian philosopher Georgio Agamben would call it) – but an exception that, as the title suggests, awaits the future life. Agamben feared that camps – from Auschwitz to Guantanamo – revealed the “nomos of the modern” and that it signaled the rise of totalitarianism, not against democracy but in fact through democracy. But here on Camp Zaatari, something more radical is on display, for it is here that the Arab revolutions go back to point zero of their history.

|

|

| Syria’s war children suffer mental illness |

What Agamben was theorising was the condition of the camp as a state of exception, where sovereignty becomes absolute. On the site of Camp Zaatari, the bared lives of the campers are the naked subjects of the sovereignty. Law here has categorically lost its self-transcendence. Agamben takes the camp as that state of exception that does not prove the rule but in fact has become the rule. Rizzi’s camera demonstrate and navigates the moment when the state of exception has become the rule, but not sustaining the rule – here that rule is being re-written.

In the same spirit that in his Remnants of Auschwitz (1998), Agamben engaged with the issue of the manner in which one can bear witness to the horrors of the camp, Rizzi’s camera becomes the witness that tries to overcome the gap between the abiding truth of what is happening in front of us and the fractured facts that in fact obscure them.

For Agamben, the central figure of Muselmann is what best represents the condition of “the bare life”, of the living dead, the dead person walking, both bearing witness and being witnessed at one and the same time. Agamben proposes the figure of the Muselmann as the apparition between the human and the inhuman. On the site of the Syrian camps, Agamben’s Muselmann has become a Muslim. The fact and the phenomenon have fused – and the fear of the Muslim (the rampant Islamophobia) has met with the fear of the Muselmann on a concentration camp that is the promise of the future of the Arab and Muslim world, where the camp has become the building block of the future urbanity.

Syrian camps are the building blocks of their future – these are not death camps, they are in fact life camps, where the children of the future Syria are born and raised, awaiting their return to their homeland. But contrary to Palestinians, these Syrians’ homeland is not occupied by European colonisers. It is occupied by dead ideologies fighting their last pitch battle.

What is the difference between Zaatari and Guantanamo Bay? Guantanamo Bay is the ruin of this (American) empire, the ruins that this empire leaves behind as it goes about trying to conquer a world that is increasingly unconquerable – precisely in the same manner that Sabra and Shatila and other Palestinian refugee camps are the ruins of European colonialism that calls itself Zionism. Zaatari is the camp where the future citizens of the emerging Arab republics, having exhausted their postcolonial promises, are born. Zaatari is exactly the opposite of Guantanamo Bay – it promises rebirth, where Guantanamo delivers despair.

|

|

| Al Zaatari refugee camp interview – Ahmed |

In his “Al Intithar”, Mario Rizzi has captured the historic moment when the new citizens of the new Arab republics are being born. This is a moment of pause – a momentous pause – when the history of the Arabs is being re-written. It is a world-historic moment, a moment no living human being has ever witnessed, lived, or experienced. On the site of the Zaatari camp, the liberation geography of all successive generations is being mapped out. People – Syrians – have left their cities and squares and homes as the foot soldiers of history, whether they are fighting on the side of Bashar al-Assad or the side of his nemesis, are sorting out their differences. When the dust of their desperate wars are over, these Syrians will go back to reclaim their homeland, people it with steadfast ordinariness – and no dictator, no fanatic, and a fortiori no colonial machination, or imperial design, can rule these people with despair anymore. This is not a wish, a daydream – this is the evident fact of a people having gone back to point zero of their history, to reimagine it anew.

The end of “the Middle East”

Camp Zaatari marks the end of “the Middle East” – and the beginning of a new cosmopolis: The evidently sudden rise of democratic revolutions from Morocco to Syria and from Iran to Yemen – extending far beyond the Arab and Muslim world – has placed a categorical hold on that most pernicious of all colonial inventions: “The Middle East”. Whether it was first used by the British colonial officers in the mid-Nineteenth century to refer to areas between Arabian Peninsula and India or by the American naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan to refer to the areas around the Persian Gulf, what we are witnessing unfold right in front of our eyes is the fading out of that colonial geography of damnation and domination into an open-ended geography of liberation. You may look at Egypt, Syria, Bahrain, Palestine, Iraq, all the way to Afghanistan and wonder how. But you need to look at Camp Zaatari and learn why.

What ever the emerging contours of that geography, “the Middle East” is no more – for what is happening is the middle, or near, or far, to no East of any colonial officer who once sat in London or Washington, DC and cast a long, lasting, and domineering gaze across the Mediterranean. The Egyptian revolution, triggered by that of Tunisia, and while both have a long way to go to come to any meaningful results, has already recentred the world. The post-American world, in earnest, has started, and “the West” is no more, or “the East”, and what does not exist has no “middle”. Mario Rizzi’s camera in Zaatari camp has captured for posterity that moment of birth.

|

|

| Al Zaatari refugee camp interview – Nael |

To achieve that postcolonial geography of liberation, the battle we need to wage against counter-revolutionary narratives (pulling the world back into status quo ante) is no less urgent than the heroic battles that Egyptians, Tunisians, Libyans, Syrians and others are waging against political despotism, military interventionism, or depleted ideologies that have ruled over them for too long. Neither pan-Arabism, nor indeed pan-Islamism -which are only the mirror images of the Islamophobia that is now plaguing Europe and North America – will do. These revolutions fortunately have no charismatic leader – and they are headed towards no pre-destined conclusion, by any grand narrative, Islamism or otherwise. Their commencement is the end of Nasserism, Musaddeqism, Nehruism, and not their regurgitation.

These revolutions are not against “the West”, for “the West” – as the imaginative geography of our domination, and in the fabrication of which we “Orientals” ourselves have been co-conspirators – no longer exists. This round of uprisings is no longer between an abstract modernity and a belligerent tradition. All these tired old cliches are now in the dustbin of history. The new history is beginning at the site of Camp Zaatari, where Syrians have gone to give birth to their future. When the carnage of Bashar al-Assad and his militant nemesis is over, the Syrians will go back from Camp Zaatari to build their democracy. This is now not obvious in the heat of the battlefield – but it is evident in the ruins of Camp Zaatari.

The wretched of the earth are grabbing the bastards who have used and abused them by the throat. The world has been mapped out multiple times over. The colonial mapping of the world, with “the Middle East” as its normative epicentre and Israel as the last colonial flag still casting its European look on the regional history, is now witness to the shadow of their own demise. Afghanistan is the current site of imperial hubris, the Islamic republic, the last aftertaste of colonised minds that crafted an Islamic ideology, looking askance at the very last Arab potentate ruling de facto postcolonial nation-states, now rising to reclaim historical agency to remap their world – and on that emerging map Camp Zaatari is the new cosmopolis.

Hamid Dabashi is Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York. He is the author of Arab Spring: The End of Postcolonialism (2012).