How one religious scholar fought for women’s rights and won

Reforms in the 19th century placed women so squarely in the foreground and yet achieved little for them, long-term.

|

| Raja Ram Mohan Roy argued in 181 against sati – burning widows on their husbands’ funeral pyres [GALLO/GETTY] |

Oxford, United Kingdom – “Tradition” is usually taken to be an obstacle to reform. “Traditional societies” are assumed to be reluctant to change, or worse, harbour nostalgic notions of going back to some mythical golden age. Gandhi was criticised for imagining an India of ancient “village republics” for which no historical evidence could be found. In the Islamic world, traditionalists are often assumed to wish to return to medieval times, in a pejorative sense. In many contexts the term “traditional” is actually used to mean “backward”. But can some “traditionalists” bring about radical social reform of a very “modern” sort?

One of the hallmarks of backwardness is how “traditional” societies treat women. Typically, the range is from everyday subordination to serious oppression. The issue of the place of women in society is ever present in the recent political upheavals throughout the Arab world – a world of “traditional” societies – or in Western attempts to rebuild Afghanistan, for example.

Democracy, after all, is supposed to be a great equaliser. However, at the heart of every debate about radical reform in any society is the question of whether change can only be brought about by discarding “tradition”, or by re-discovering the true meaning of “traditions”, after shedding misconceptions that had built up over the years.

|

|

Some people argue that it is not possible to give a “liberal” twist to ancient scriptures and commentaries which were composed in very different times. According to this view it is best to leave such “traditions” in history, where they belong, and move on. This may well be the sensible way forward. But if any successful reformists applied tradition to bring about major social reform, in particular the removal of oppressive and cruel customs towards women, it might be a good idea to learn what they had to say and why they succeeded.

Hindu widow remarriage

There is one such striking example from India: Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and the campaign for Hindu widow remarriage during the great Indian social reform movements of the 19th century. Ishwar Chandra Bandyopadhyay, known as Vidyasagar [“Ocean of learning”], is an iconic figure in the history of Indian social reform. He was a Bengali Brahmin Sanskrit scholar.

His image is that of a quintessential pandit, traditionally dressed in dhuti-chador. This was no Anglicised “brown sahib”. Yet this Sanskrit scholar battled to end child marriage and high-caste polygamy, and to enable Hindu widows to re-marry. He succeeded in getting legislation passed to permit Hindu widow remarriage, despite fierce opposition from many within his own community – and married his own son to a widow as an example.

In our times, this might be the equivalent of a Quranic scholar leading a feminist revolution in an Islamic country. Was this just an exceptional individual and a fortunate turn of events? Or are there relevant political lessons that we might draw in terms of motivation, timing, negotiation and external intervention, that culminated in the Hindu Widow’s Re-marriage Act in 1856?

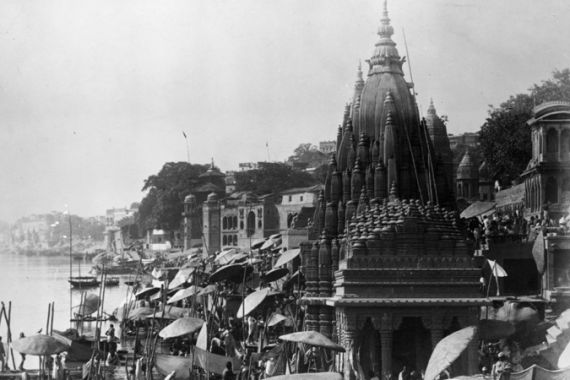

The plight of Hindu widows in India gained international notoriety recently when Indian film-maker Deepa Mehta tried to shoot her film Water in Varanasi, one of the “holy” cities to which widows were traditionally packed off to live out their lives in penury, often preyed upon by the hypocritical lechery of patriarchal societies. Even though Mehta had been given permission to shoot her film there by the Indian government, which had first inspected the script, she and her crew faced angry mobs accusing her film of being “anti-Hindu”.

She had to abandon filming in India, and eventually, shot the film several years later in Sri Lanka. Mehta’s film was set in the 1930s, nearly 80 years after Vidyasagar’s successful campaign to change the law. But stories about the ill-treatment and marginalisation of widows in India appear in the media even today. As we all know, legislation does not change society; the real revolution is that one within people’s minds.

Modern reforms

What is fascinating about Vidyasagar is the way in which a traditional Sanskrit scholar in a patriarchal society used his command of the ancient scriptures to argue against opponents in his own community, and to campaign for very “modern” reforms, against child marriage, polygamy and the mistreatment of widows. He set an example of enlightened leadership from within cultural or religious communities for the progress of their own people.

|

| The plight of Hindu widows in India gained international notoriety when filmmaker Deepa Mehta tried to shoot her film Water in Varanasi [GALLO/GETTY] |

Columbia University Press has now published the first complete English translation of his two books on Hindu Widow Marriage, translated by Brian Hatcher, Packard Chair of Theology in the Department of Religion at Tufts University in the United States, together with a lengthy analysis of Vidyasagar’s campaign for widow remarriage.

The English translation, both of Vidyasagar’s arguments in Bengali and his copious references to the Sanskrit texts, makes his case for social reform accessible in full for the first time to readers around the world. Curious readers may well be fascinated, if sometimes disheartened, by the glimpses of the Hindu scriptural view of society at large, quite apart from the perspective on women that emerges from the passages quoted by Vidyasagar to make precise logical points.

For instance, a passage from Parashara, one of the most important of the treatises that forms the basis of a legal code in orthodox Hinduism, states: “If in dire circumstances a Brahman eats in the house of a Shudra, he may be purified by mental anguish or by one hundred repetitions of the Drupad formula.” Subsequent passages demonstrate how various foods may be eaten by Brahmans in Shudra homes even if circumstances are not that “dire”.

However, for those less inclined to delve into “shrutis” and “smritis”, Hatcher’s critical analysis of the reform movement is a must-read. It charts earlier attempts at reform by Indians, the uproar in the orthodox Hindu community caused by Vidyasagar’s proposals, the debate over the use of scriptures for “modernist” reforms, and the complex historical interactions between the colonial administration and Indian social reformers, which may explain the successful passing of legislation against “sati” (burning widows on their husbands’ funeral pyres) and for widow remarriage – and the failure of the campaign against high-caste Hindu polygamy.

Abolition of ‘sati’

Crucially, it highlights the novel ways in which Vidyasagar waged his reform campaign, using colloquial language and, effectively, mass media of the time, to reach a wide audience and start a genuine public debate. One gets the distinct impression that had he been around today, Vidyasagar would have been blogging and an avid user of online social networks.

It is commonplace in the West to refer to reformist legislation such as the outlawing of “sati” as British efforts to eradicate barbarous practices in their colonised lands. Indigenous reform efforts tend to get obscured in the colonial history of “benevolent paternalism”, as does the effect of the meeting of East and West.

Raja Ram Mohan Roy, considered the father of modern India in many respects, argued against “sati” as early as 1818, using both “rational” argument and scriptural justification. By a fortunate historical accident, the liberal-minded William Bentinck arrived as Governor-General ten years later, providing Roy a powerful ally. He passed a law abolishing “sati” in 1829.

The demand for widow re-marriage had actually been raised in Bengal as far back as 1757, when Raja Rajballav of Vikrampur sought sanction for the remarriage of his widowed daughter. The pandits he consulted ruled that widow remarriage was allowed by Hindu law, but were opposed by the more orthodox Raja Krishnachandra of Nadia. Several others discussed reforming the practice in the years that followed. Vidyasagar’s successful campaign must therefore be considered in the context of this background, as well as his own significant efforts.

Vidyasagar first published an essay against child marriage in 1850. Five years later, he wrote his first essay arguing in favour of widow re-marriage in the reformist journal Tattvabodhini Patrika. It caused a storm in the Hindu community and brought Vidyasagar “instant notoriety”. Orthodox pandits gathered to oppose him. “Some opponents were simply too inured to long-practiced evils; others were clearly afraid of the powerful faction leaders who could threaten supporters of the cause with social ostracism,” writes Hatcher in his introduction to the text.

|

|

Within a month, Vidyasagar published the essay as a short book, a thousand copies of which were snapped up so fast that 3,000 more had to be printed right away. In the end, a reported 15,000 were sold, making Vidyasagar’s book a controversial bestseller of his day.

‘Prizes to oppose Vidyasagar’

To answer the criticisms of his first book, Vidyasagar published his second, much longer book, a few months later. Of his critics, he wrote: “I want to thank them a thousand times over… I would have been far more troubled had they shown no concern or been too indifferent to reply.”

His critics had not always displayed the same civility. They appear to have fallen into three categories. There were those who argued that it did not matter what the ancient texts stated; what mattered was the custom as practiced over centuries. A second group reflected the nascent nationalism taking hold of India: as India was not ruled by a representative body, its legislative interference into local customs was improper. The third group reacted with shrill hysteria: they “questioned the vitality of Vidyasagar’s faith as a Hindu … They also questioned his bona fides as a pandit….They even at times questioned his basic grip on reality,” notes Hatcher.

Some of the denunciations came from people who had supported reform in the past, but changed sides, most likely due to the orthodox views of their wealthy employers. Prizes were offered to oppose Vidyasagar. Often, the criticisms had little to do with scholarship and more to do with politics or careerism. But by using the local spoken language and the new technologies of print media, Vidyasagar had widened the debate and was willing to let the public make up its own mind.

Legitimate questions have been raised, such as, why should “modernist” reformers expend so much energy on using ancient scriptures as justification? Similar questions are asked of those who try to offer a “liberal” or “modernist” interpretation of religious texts in Islam or Christianity. Is that really possible, it is asked, or should one merely say, “that was then, this is now”? By relying on “traditional” texts, it is argued, one further enshrines their legitimacy.

A congruence of interests between reformers and those wielding political power is clearly a key factor for successful legislative reform. By the time Vidyasagar attacked the practice of polygamy among high-caste Hindus in the 1870s, the revolt of 1857 had created an unbridgeable chasm between Indians and their colonial masters. Indian nationalists were more interested in “cultural preservation” and the British had lost their reformist motives. The campaign failed.

Hatcher has argued that Vidyasagar’s “genius lies in … advancing a contemporary reformist cause in terms faithful to his own intellectual heritage”, a sentiment which would probably resonate across societies striving to emerge beyond the Western hegemony of thought and communications that has lingered for so long after the end of territorial domination.

But equally, it might be asked why “the great reforms of the 19th century placed women so squarely in the foreground and yet achieved so little for them in reality”? Was it because changing mindsets is inherently a very gradual process, or was it because the means employed – interpretation of scriptures – was itself ultimately self-defeating?

Sarmila Bose is Senior Research Associate, Centre for International Studies, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford. She was a journalist in India for many years. She earned her degrees at Bryn Mawr College (History) and Harvard University (MPA and PhD in Political Economy and Government). She is also the grandniece of Subhas Chandra Bose.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.