Khamenei’s power consolidation gambit

Recent insinuations by Ali Khameini shows a political struggle between the supreme leader and the president.

|

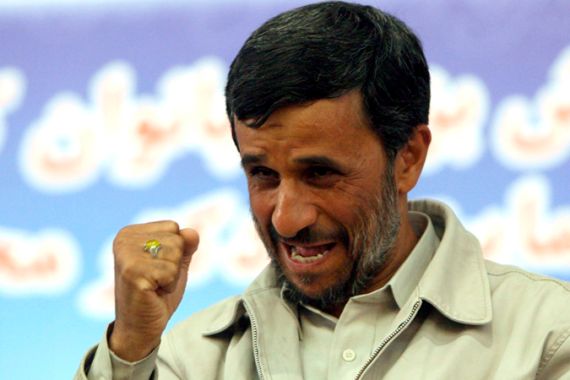

| A power struggle between Khameini and Ahmedinejad might lead to the abolishment of the presidential post [EPA] |

Recent comments by Iran’s Supreme Leader have sparked intense debate inside the Islamic Republic. When Ayatollah Ali Khamenei hinted at abandoning Iran’s presidential system three weeks ago, a flurry of commentary followed. Some interpreted his remarks as a concerted push towards absolute power, while others warned against further damaging the country’s republican institutions. It is now clear that the Supreme Leader has embarked upon a sustained strategy of eliminating political opposition; decreasing turbulence during his reign, and shaping Iran’s long-term political development around his rule.

Indeed, a series of public manoeuvres by prominent conservatives shed light on long-standing (and until recently, private) project put in place by Ayatollah Khamenei – which has now been completed. Most recently, conservative parliamentarian, Mohammad Dehghan, followed the Supreme Leader’s comments by announcing that Khamenei’s expert committee has already finished amending the constitution. Thus, barring an unforeseen change of heart by Supreme Leader Khamenei, the Islamic Republic will no longer hold elections for a directly elected president. Dehghan’s comments reveal that over one year ago, the Supreme Leader formed an expert committee to permanently amend Iran’s constitution.

The Supreme Leader’s conservative followers have led the public discourse on abolishing Iran’s presidency. Majles Chairman, Ali Larijani stressed Khameni’s musings were “anti-dictatorship,” and instead “will help better coordinate the activities of the three branches of the government” – a targeted response to accusations that Iran is turning into an autocracy. Parliamentarian Hamidreza Katouzian also stated: “A notion has been recently discussed…that in a country blessed with the Supreme Leader, there is no need for a president…the country can have a prime minister appointed by the parliament.” Katouzian’s remarks laid the groundwork for Iran’s most powerful man to enter the fray.

With the benefit of twenty-twenty hindsight, Khamenei’s consolidation should come as no surprise. Presidential elections have long been problematic for his accumulation and projection of power. During Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani’s presidency, it was often unclear which man wielded more power. What Khamenei then lacked in religious credentials and political prestige, he made up for by cultivating close ties to Iran’s security and hard-line clerical establishments. Mohammad Khatami’s presidency was the foremost challenge to Khamenei’s rule. Khatami’s ascent represented the birth of Iran’s reform movement, and a larger debate within the Iranian system over the future of its power structure development.

One thesis – favoured by reformists and pragmatists – supported reducing the powers of the Supreme Leader and empowering the Presidency. The opposing thesis – favoured by various conservative factions that have increased in political prominence over the past decade – supported turning the president into a quasi-prime minister with the Supreme Leader at the helm of policymaking. However, the reformist effort to develop civil society, and in turn strengthen the reform movement to push for deep changes in the system, did not go unnoticed by Khamenei.

Throughout his tenure as Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei has utilised control of Iran’s judiciary to enforce his rules. When the legislative branch became an obstacle during the refomist-dominated sixth Majles – with the chairmanship of Mehdi Karroubi – Khamenei countered. Utilising the judiciary, he purged nearly all sitting reformist parliamentarians. Each Majles since has coalesced around his rule. With the Judicial and Legislative branches showing fealty, Khamenei set his sights on the Executive. In 2005 and 2009, contested presidential elections were used to eliminate political opposition and send a message to conservative factions that full allegiance to Khamenei was non-negotiable.

In addition to boycotting Iran’s 2012 Majles elections, the great hope for the Green Movement was centred on the 2013 presidential elections. Khamenei’s plan to abolish the presidency was thus predicated on decreasing the possibility of turbulence from other power centres. With reformist politicians calling for a boycott, a confident Khamenei has sought to checkmate his opposition. A boycott was the primary hope for Iran’s reformists to punish and increase pressure on the Supreme Leader. By abandoning the presidency, Khamenei is punishing reformists by cutting their popular base and permanently removing their vehicle for pressuring the system into making changes.

Ayatollah Khamenei has a long-standing track record of political counter-moves that seek to secure an Islamic Republic governed under his rule. Throughout 2010, he strategised on securing his system for the future – doing so in silence. It is now clear that Supreme Leader’s hidden management team and Security Council has thus far been successful. What would have been considered shadow government structures fifteen years ago are now the governmental bodies running the Islamic Republic.

The primary objective of the Supreme Leader’s power consolidation gambit is to ensure that all power centres prioritise executing his directives. Prominent conservative factions have accepted the central role of Ayatollah Khamenei and a domestic vision for Iran that is more Islamic than democratic. Iran’s opposition has accepted neither Khamenei’s central role nor his vision, but their options for pushing back are increasingly limited. Barring unforeseen domestic political upheaval, this is likely to remain the status quo.

Sahar Namazikhah is an Iranian journalist based in Washington DC and previously editor of several daily newspapers in Tehran. Reza Marashi is Director of Research at the National Iranian American Council and a former Iran desk officer at the U.S. Department of State.