How a ragtag army defended Bosnia and Herzegovina against two aggressors

ARBIH, formed in April 1992, managed against all odds to successfully defend the country’s sovereignty.

![ARBIH Krajina [Courtesy of Faruk Sehic/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_9273-1713293303.jpg?resize=770%2C513&quality=80)

Faruk Sehic’s left foot was so heavily injured in March 1994 that he couldn’t walk.

He’d just been hit by shrapnel on the battlefield of Hasin Vrh mountain in western Bosnia.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBosnian Serb leader Dodik stands trial for defying peace envoy

European Commission to recommend EU accession talks with Bosnia

Schrödinger’s genocide

Having broken the front lines of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBIH), Serb forces (known as VRS, Army of Republika Srpska) were near enough that Sehic could hear them shouting to each other.

As Serb forces fired shells at them nearby, his colleague was carrying him, but with each detonation, they would fall to the ground.

The outcome did not look good, but surrendering was never an option for the young commander, 24 years old at the time.

“I had some bullets in my automatic rifle, and I was thinking completely rationally to kill myself so that I’m not captured alive and tortured,” he told Al Jazeera from his home in Sarajevo. “It’s better to decide for yourself.”

Sehic did not know of a single soldier from his brigade who made it out alive after being captured.

But before he would pull the trigger on himself, special units of the ARBIH arrived just in time, saving their front line and their soldiers.

April marks the 32nd anniversary of the start of the war in Bosnia, which caught much of its population off guard.

On April 15, 1992, Bosnia’s armed groups united and ARBIH was officially formed to defend the country’s population and sovereignty against attacking Serb forces who wanted to create a greater Serbia and were supported by Belgrade.

Later into the war, ARBIH also resisted Croat forces (known as HVO) whose goal was creating a Greater Croatia, directed by Zagreb.

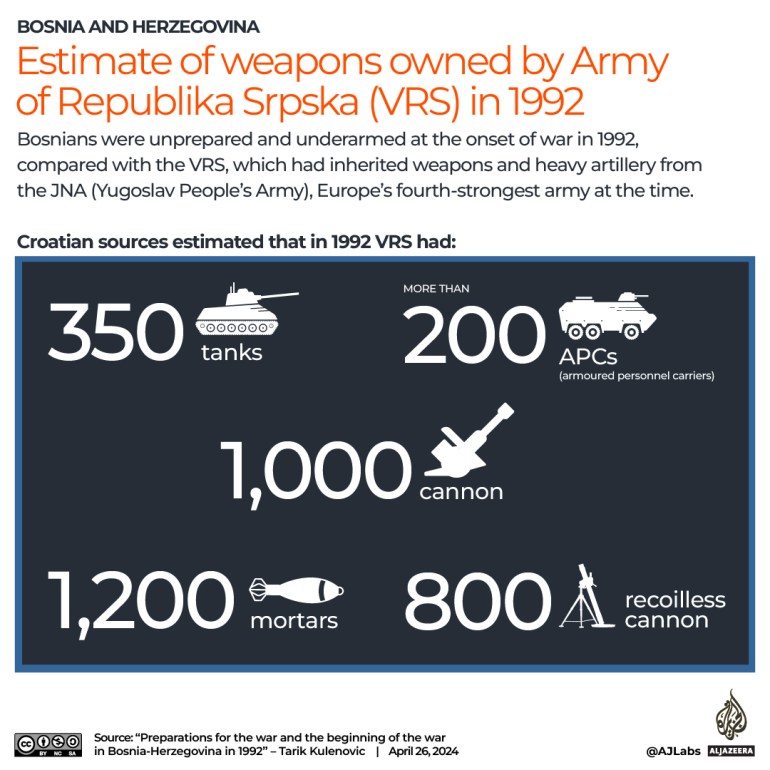

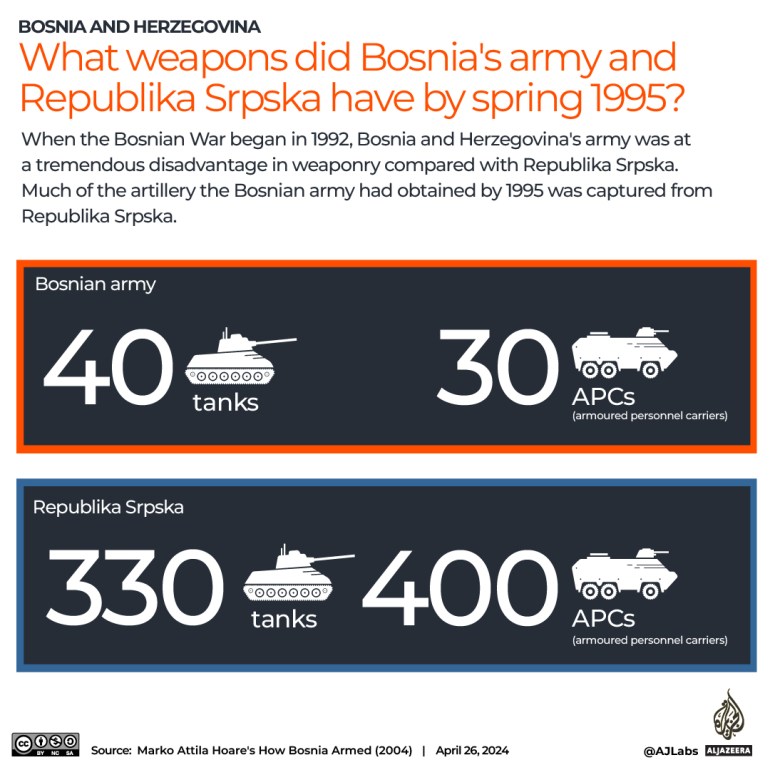

The UN Security Council imposed an arms embargo in September 1991 for territories of former Yugoslavia, following the war of independence in Slovenia and then Croatia. The embargo lasted for the entirety of the Bosnian war, with the argument that if the embargo was lifted, it would fuel more bloodshed.

But in reality, it disproportionately limited ARBIH’s chances of defending the country and its civilian population as Serb forces, for instance, were already heavily armed having inherited the stockpile of the JNA (Yugoslav People’s Army), at the time the fourth strongest military force in Europe.

Despite being caught unprepared and defenceless, the ARBIH managed against the odds to fight Serb and Croat forces.

In March 1992, 22-year-old Sehic was studying veterinary medicine in Zagreb, the Croatian capital when the Serb Volunteer Guard (also known as Arkan’s Tigers), a Serbian paramilitary unit headed by the Serbian strongman Zeljko Raznatovic (Arkan), began heavily attacking Bijeljina, a town in northeastern Bosnia by Serbia’s border, at huge human cost.

![The 'Tigers' were first accused of war crimes during fighting in Croatia 1991 [Ron Haviv/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/201412872927851734_20-1714126288.jpeg?w=570&resize=570%2C380)

Yugoslav army units and Serb paramilitary forces continued their campaign of “ethnic cleansing” as they made their way south along eastern Bosnia, killing civilians in Zvornik, Visegrad and Foca.

Evident that a war was starting, Sehic returned to his hometown of Bosanska Krupa in western Bosnia in April 1992 to defend the country.

“My dad gave me a rifle he took off a dead Serb soldier, and I joined the Territorial Defence (the first armed forces in Bosnia, that later officially became ARBIH).”

On April 21, 1992, gunfire started in Bosanska Krupa and Sehic, along with all of his friends and local acquaintances joined the defence, wearing and owning nothing more than their civilian clothes – jeans and sneakers.

They became refugees overnight, Sehic said, as Serb forces had occupied the right side of the bank where their homes were.

![ARBIH [Courtesy of Faruk Sehic/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/800_0821-1713293768.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C514)

‘Tremendous disadvantage’

At the start of the war, ragtag groups of civilians-turned-defenders formed spontaneously across the country with whatever weapons they had – mostly hunting rifles and outdated guns.

In May 1992, they managed to defend the capital and the presidency from occupation when the JNA and Serb fighters attempted to force the legal government to surrender.

With scarce means and without military equipment, citizens managed to defend the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina.#SarajevoUnderSiege 21/24

Photo©️Jordi Pujol Puente pic.twitter.com/xsI9TuosL5— SniperAlley.Photo (@SniperAlleyPhot) May 1, 2020

By the end of the war, the loosely connected groups of defenders had evolved into seven corps and were quickly reclaiming back territory in Bosnia.

Manpower wasn’t a problem as some 200,000 people had joined to help.

The morale to defend Bosnia was high and the troops were young. Many were just 16 or 17. Few were older than 25.

“There was this big, positive idealism … people have this biological instinct that gives you huge energy,” said Sehic.

“My ideal was a Bosnia which was multiethnic, multireligious, multicultural, single, whole, undivided, independent … these were words that we, ordinary people, believed in. We fought for this idea, for Bosnia.”

According to Marko Attila Hoare, historian and associate professor at the Sarajevo School of Science and Technology, the VRS meanwhile had “suffered from increasingly poor morale, resulting from their involvement in systematic atrocities against civilians and from unclear war aims”.

“The Bosnians began the war in 1992 at a tremendous disadvantage, given their leadership had not expected war while their fledgling armed forces were woefully underarmed in comparison to the great Serbian aggressor,” Hoare told Al Jazeera.

“But the pressure of fighting a war for national survival against genocidal destruction steadily distilled into the Bosnian defenders the morale and discipline needed to resist successfully, while Bosnia and Herzegovina’s military leadership steadily established an efficient military organisation and managed to capture or import more weapons.

“Even after the aggressor occupied around 70 percent of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the first year of the war, the defenders still occupied the heartland around the Sarajevo-Zenica-Tuzla triangle, with greater resources of manpower than were possessed by the so-called ‘Republika Srpska’.”

‘Insanely brave’

The obvious differences in the quality and quantity of weaponry meant the odds were stacked against Bosnia’s survival.

General Jovan Divjak, deputy commander of ARBIH, said in February 1995 that from more than 200,000 Bosnian soldiers, only 50,000 were armed.

“Not one of our units is fully armed because of the arms embargo,” he said.

Sehic said in the beginning, the diaspora collected and sent money to the brigades, which they used to buy ammunition, bullets and guns flown into an improvised military airport near the town of Cazin by hired Ukrainian pilots from Croatia.

But when HVO attacked ARBIH in early 1993 and a separate war ensued between the two, that route of supplies also came to an end.

Sehic recalled they only had light weapons and no armoured vehicles, while Serb forces had heavy artillery and “everything that we didn’t have”. The Fifth Corps had only two or three tanks which they had captured from Serb forces. Most of ARBIH’s heavy weaponry was obtained by capturing it from Serb forces on the battlefield.

“That was the case in the rest of the corps. We made up for the lack of weapons with our courage,” Sehic said.

The battle at the mountain of Hasin Vrh against Serb forces in the winter of 1994 where he was injured, was particularly difficult, so much so that one shift lasted for 48 hours, he recalled.

It was of paramount importance to defend their position at the plateau – if Serb forces were to descend, they would take control of the hydroelectric power plant a few kilometres away that was the only source of electricity in the region.

Full of energy and enthusiasm, the troops ascended the hill towards the front line. A fierce battle with 1,000 soldiers, including the respected 505 Buzim Brigade led by the renowned commander Izet Nanic, awaited them.

Dressed in white to blend in with the snow, it was difficult, rocky terrain and they were fighting for a small space of just 100 metres (328 feet).

“In those positions at the top … they were shelling us the whole day and then attacking on foot,” Sehic said. “Unfortunately, we didn’t have enough shells to reciprocate whenever they shelled us.”

They managed in the end to defend their position but due to a lack of weaponry, especially shells, the ARBIH suffered significantly during the two-month offensive. Some 371 of their soldiers were killed, including many from Sehic’s unit.

In his 511 brigade of more than 2,000 people, 503 soldiers were killed during the war – “a huge number”, with many more injured.

Rade Rakonjac, a member of the Serb Volunteer Guard and Arkan’s bodyguard, attested to the achievements of Bosnian troops in an interview with the Serbian Happy TV channel.

“That Fifth Corps, especially the 505th Buzim Brigade, they’re fierce fighters,” he said.

“The 505th Buzim Brigade, it’s something unbelievable. As much as they are our enemy, I always spoke words of praise [about them]. Because they’re really – but really brave; if you can say they’re insanely brave, then they’re insanely brave.

“Seventeen military actions on Plazikur, a hill in front of Velika Kladusa [in western Bosnia] – 17 military actions, 17 attacks and we couldn’t move them (from their position); it’s unbelievable.”

Sehic, quick-thinking and able to control his fears in a war zone, was promoted to platoon commander.

“Whoever is faster, whoever sees better, that person will win. Everything unravels very quickly,” he said. “The speed of your reaction will save you.”

Following Croatia’s Operation Storm in the summer of 1995, during which it regained its territory in Croatia proper from rebel Serbs, ARBIH in September retook swaths of land back and freed towns.

“The goal [from the beginning] was to go back home … and we did return, we freed our city,” Sehic said.

In autumn of 1995 as a platoon commander, he led a unit of 135 men and on September 17, 1995, the 511 Brigade troops which Sehic was a part of, liberated his hometown of Bosanska Krupa.

As for the HVO, Hoare said they were dotted all over Bosnia.

“When it joined the aggression against Bosnia, its units were frequently left vulnerable and unable to defend themselves from the more numerous Bosnian army.

“The ARBIH essentially defeated the HVO during 1993. Coupled to this, the US put pressure on the Tudjman (president of Croatia at the time) regime in Zagreb to make peace with and cooperate with the ARBIH, resulting in the Washington Agreement of March 1994. This led to Croatian-Bosnian military cooperation against the overextended Serb front lines, which the Great Serbian forces were wholly unable to defend.”

The Dayton peace agreement formed in November 1995, brought an end to the war but also ARBIH’s advancements on the ground. The peace deal divided the country along ethnic lines into two entities – the Bosnian-Croat-run Federation entity and Republika Srpska entity, run by Serbs.

Although Bosnia remained a whole country with its borders intact, three decades on, the country still struggles to move forward, with the president of Republika Srpska, Milorad Dodik, a denier of the Srebrenica genocide, doubling down in his calls for Republika Srpska’s secession.

Over the years, his threats of seceding and joining Serbia have grown steadily.

“[The situation now] is worse than war. In war, you know who your enemy is, you know what you’re defending and why. You could be hungry, thirsty. Now it’s as if there’s some kind of peace, but Dodik is always threatening secession,” Sehic said.

“In Sarajevo, the politicians say (known as the ‘Trojka’): ‘There won’t be a war, it’s just an election campaign’, but an election campaign can’t last for 25 years.”

Recalling the people’s ideal of an undivided, multiethnic and multireligious Bosnia for all, Sehic said: “[The country that] we have now with Dayton, it was imposed on us. But Bosnia still exists as a country. There is that idea that remains in us that maybe one day there will be such a country.”