US elections 2024: Who is Republican challenger Mike Pence?

As Trump’s vice president, Pence offered evangelical ‘balance’ to the White House but broke ranks to certify 2020 election.

Former United States Vice President Mike Pence has become the latest Republican to announce a bid for the party’s ticket in the 2024 presidential election, setting up a race that will see him attempt to chip away at the early lead of his former boss, Donald Trump.

Announcing his candidacy on Wednesday, Pence said the US needs a leader who will “appeal, as (Abraham) Lincoln said, to the better angels of our nature”. He outlined a platform that he said would pivot away from the theatrics of the modern-day Republican Party and focus on more staid conservative principles.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsPence booed at NRA meeting in US as he tries to outflank Trump

Former US Vice President Pence testifies before grand jury

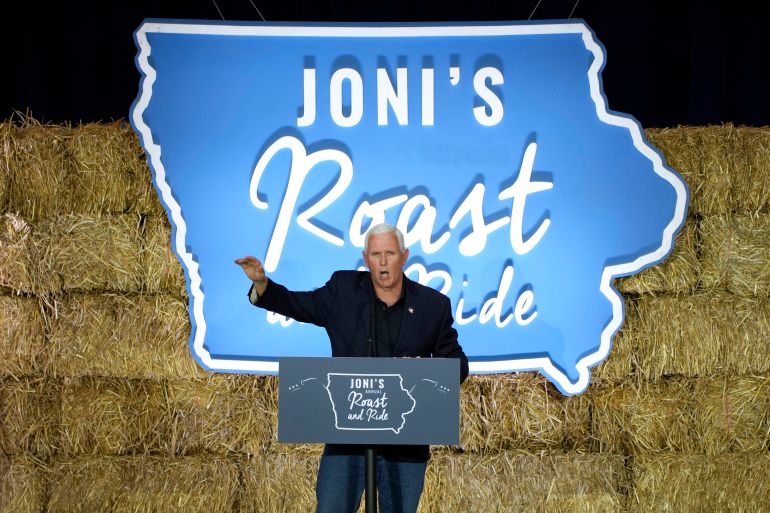

Campaign operatives have said Pence will seek a surge of support at early caucuses in the Midwestern state of Iowa, which the Republican likened to his home state of Indiana. Previously, as Indiana’s governor from 2013 to 2016, Pence shepherded into law controversial abortion restrictions and so-called religious freedom bills that reverberated nationally.

Those conservative bona fides made him a strong running mate during Trump’s 2016 race for president. A consistent proponent for religiously oriented conservative politics, the 63-year-old Pence brought self-proclaimed “balance” to Trump’s scandal-ridden — and ultimately successful — election bid.

But while the former US congressman and Indiana governor served as a loyal deputy to Trump during his four years in the White House, he became the subject of scorn when he moved to certify US President Joe Biden’s 2020 election victory on January 6, 2021.

Even for those who continue to see Pence’s conservative “steady hand” as a counterpoint to Trump, it remains unclear if the goodwill will actually translate into primary votes, said Andrea Neal, author of the biography Pence: The Path to Power.

“Many of the conservatives I know in Indiana would probably say … this is a decent man. This is an honest man. This is someone who states clearly what his principles are, even when they go against the grain of the moment,” Neal told Al Jazeera.

“But I think a lot of conservatives would also say, ‘I’m sorry that I can’t support Mike Pence because I don’t think he has a chance of winning.'”

Early life

Born in the small city of Columbus, Indiana, Pence was raised Catholic and began his early political life as a Democrat. By his own accounts, he underwent a political and religious conversion in college, spurred by an experience at a Christian music festival.

That experience began a transformation that saw Pence increasingly embrace evangelicalism, an umbrella term for a branch of Protestantism that emphasises spreading, or evangelising, a specific interpretation of Christianity. Evangelical groups have emerged as some of the most influential forces in US conservative politics, particularly in terms of opposing abortion and restricting LGBTQ rights.

“People still are perplexed when they find out that, the first time he voted in a presidential election, he voted for a Democrat,” Neal said, “because he seems like he’s a born Republican — a conservative from the cornfields of Columbus. But really, he had sort of a journey to conservatism that involves his own education, his own exposure to some of the strongest conservative minds, both nationally and in Indiana.”

Failed congressional bids against a Democratic incumbent in 1988 and 1990 — the latter of which saw Pence’s campaign run an ad that critics blasted as racist for its depiction of an Arab man — led to a decade of withdrawal from direct involvement in politics.

He instead worked in conservative think tanks and as a talk-radio host, honing an ideology and identity in which he described himself as “a Christian, a conservative and a Republican, in that order”.

In 2000, Pence ran for an empty US congressional seat, this time proving victorious. For 12 years, he would represent Indiana in the House of Representatives, a conservative rabble-rouser with his star on the rise.

‘Walks the walk’

During his tenure in Congress, Pence gained a degree of national notoriety for regularly railing against his own party, accusing its leadership of being too liberal on fiscal and social issues.

He also resisted expansions of Medicare — a government health insurance programme for the elderly — and regularly called for the government to withhold federal funds from Planned Parenthood, an organisation that provides reproductive healthcare and abortions.

In 2013, he became governor of Indiana, where he again drew national attention for his deeply conservative policies.

They included passing what at the time was one of the most sweeping restrictions in the country on abortion, which was then still federally protected under the 1973 US Supreme Court ruling Roe v Wade.

Indiana’s law banned abortions sought because of fetal abnormalities, while requiring aborted fetuses to be buried or cremated instead of disposed of as medical waste. The ban was, however, ultimately blocked by the courts.

Pence also passed a “religious freedom” law that critics say allowed businesses to discriminate against LGBTQ people, although he later amended the legislation.

Still, in his career, Pence showed the evangelical segment of the Republican Party that he “walks the walk and talks the talk”, according to Scott Waller, a professor of political science at Biola University in California.

As of 2014, about 38 percent of Republicans identified as some form of evangelical Protestant, according to the Pew Research Center. The demographic remains a significant force in the party.

“For the rank and file — and, to a certain extent, the more elite level of evangelicalism — Mike Pence is that guy, a ‘one of our own’ type thing,” Waller said.

That reputation made Pence particularly appealing to Trump’s 2016 campaign, which roiled both the business community and the more religious segments of the party, according to Justin Buchler, a professor of political science at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio.

“Trump’s hand was sort of forced by coalition politics to pick Mike Pence as his running mate,” Buchler told Al Jazeera.

“Pence, as a religious conservative, shored up Trump’s weaknesses with some of the religious conservatives in the country. And being a governor, he assuaged some of the fears of the Chamber of Commerce types who just wanted to make sure that everything would be a little bit more stable.”

For his part, “Pence took the offer thinking that it would be one possible path to the presidency for himself,” Buchler explained.

January 6, 2021

Then came the 2020 presidential election and a pressure campaign by Trump and his allies to convince Pence not to certify Biden’s election victory.

Pence, as vice president, also served as president of the US Senate. And some Trump supporters erroneously believed that position granted him the power to interfere in the counting of the Electoral College votes, a routine post-election procedure.

Pro-Trump rioters ultimately stormed the US Capitol in an attempt to disrupt the count, some of them chanting, “Hang Mike Pence.”

But the certification of the election in the hours afterwards represented to some supporters a form of rehabilitation for Pence after what many considered a marriage of convenience to Trump, according to Neal.

“I think most conservatives I know here in Indiana were proud of what he did on January 6, and the testimony that came out during the January 6 [congressional investigation] really seemed to vindicate him in many ways,” she said.

Since then, Pence has spoken out about the former president, saying, “History will hold Donald Trump accountable.” He also abandoned a fight against a federal subpoena and in April testified before a grand jury investigating Trump’s post-election conduct.

But the spectre of January 6, 2021, is unlikely to dissipate any time soon, Buchler said. Even as Pence’s actions made him a folk hero to some, large segments of Trump’s base — regularly stoked by the former president — still see the former vice president as “persona non grata”.

“From the perspective of 2012, [Pence] is exactly the kind of politician that you would expect to run for president and have a chance,” Buchler said. “But that’s not where the Republican Party is right now.”

“There’s no way to win the nomination of a party when the electoral base likes seeing people chant that you should be hanging.”