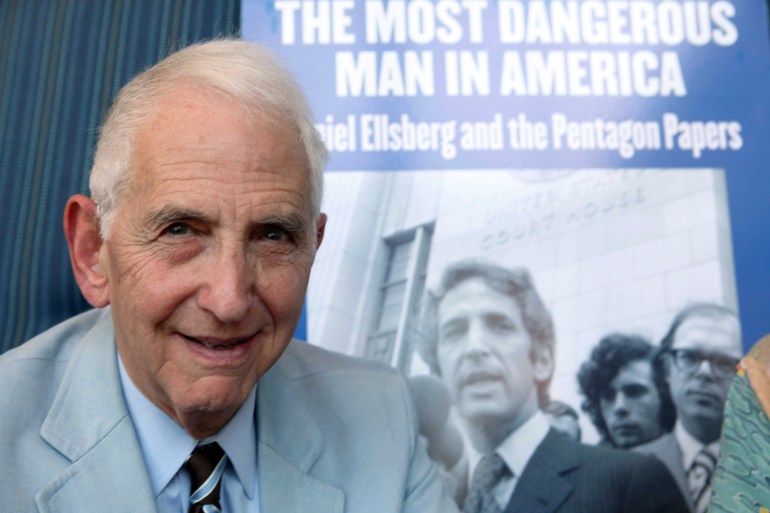

Daniel Ellsberg, Pentagon Papers whistleblower, dies at 92

Ellsberg exposed US government deception on its war in Vietnam and advocated for whistleblower rights.

Daniel Ellsberg, a whistleblower famed for exposing government deception over the United States’s war in Vietnam and an outspoken opponent of nuclear weapons, has died at the age of 92 from pancreatic cancer.

The Washington Post was the first to report that Ellsberg died on Friday, citing a statement from his family.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsUS Senator calls for probe into law enforcement mass surveillance

Top media outlets demand US end prosecution of Julian Assange

“My dear father, #DanielEllsberg, died this morning June 16 at 1:24 AM, four months after his diagnosis with pancreatic cancer. His family surrounded him as he took his last breath. He had no pain and died peacefully at home,” his son Robert said in a Twitter post on Friday.

While Ellsberg was best known for his efforts to bring a trove of secret documents known as “the Pentagon Papers” to public attention, he remained actively engaged in activism on a number of issues, such as protection for whistleblowers and the dangers of nuclear weapons, until the end of his life.

At the time of the Pentagon Papers leak, Henry Kissinger, an architect of US escalation of the Vietnam War and then national security adviser to former President Richard Nixon, called Ellsberg “the most dangerous man in America who must be stopped at all costs”.

Ellsberg had worked as a military analyst on national security issues for the Pentagon and the RAND Corporation, a prominent policy think tank, before becoming disillusioned with the US war in Vietnam and leaking thousands of pages of documents detailing government lies about the war to the media in 1971.

The episode resulted in a landmark battle over freedom of speech that made its way to the US Supreme Court. Less than two weeks after the papers were published, the court ruled that the press had the right to publish the materials leaked by Ellsberg, a crucial victory for efforts to expose government falsehoods on issues such as national security.

The US government charged him in January 1973 with theft and conspiracy under the Espionage Act, facing a maximum of 115 years in prison. The charges were dismissed in May of that year because of government misconduct and illegal evidence gathering.

Throughout his life, Ellsberg railed against the use of the Espionage Act and remained a fierce advocate for the rights of whistleblowers such as Edward Snowden and Julian Assange, both of whom released classified documents to the public revealing government abuses such as illegal mass surveillance and the killing of civilians in US wars overseas.

In a 2014 interview with Al Jazeera, Ellsberg spoke about the dangers of widespread classification of government documents and a “culture of secrecy” in the US national security apparatus.

“It’s much harder to challenge the culture of secrecy since 9/11. Just as it’s harder to challenge clearly criminal, illegal, internationally forbidden practices – such as torture,” he said.

Ellsberg was also a staunch opponent of nuclear weapons. His activism over several decades led to his arrest dozens of times.

His 2017 book, The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear Nuclear War Planner, detailed the perils of nuclear weapons and their place in US national security. It was based on his experience as a military analyst who worked on nuclear issues between 1958 and 1971.

In it, he described a moment that marked a turning point in his life and worldview: reading a government document estimating that about 600 million people would be killed in a US first nuclear attack on the Soviet Union, its satellites in the Warsaw Pact, and China.

“I remember what I thought when I first held the single sheet with the graph on it. I thought, ‘This piece of paper should not exist. It should never have existed. Not in America. Not anywhere, ever.’”

He added that “from that day on, I have had one overriding life purpose: to prevent the execution of any such plan.”

Ellsberg remained engaged with young people and activists until the end of his life, and told Al Jazeera in 2014 that he was “encouraged” by his interactions with students on issues such as surveillance.

He dedicated, The Doomsday Machine, “to those who struggle for a human future”.