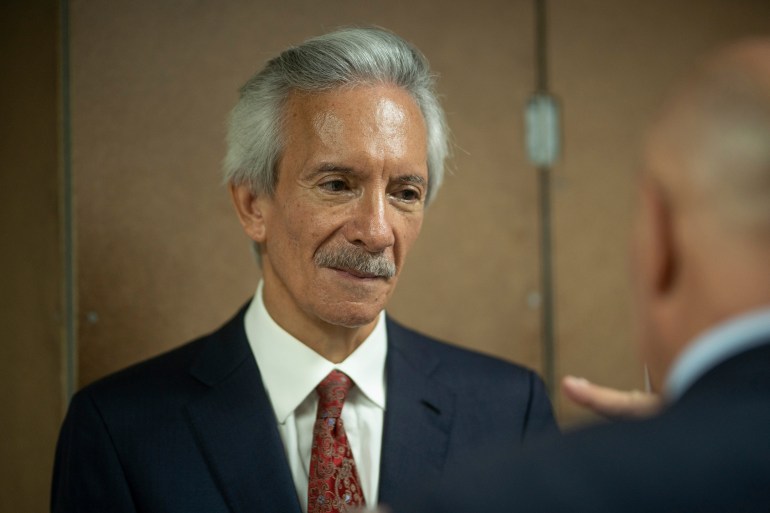

Guatemalan court convicts prominent journalist José Rubén Zamora

Critics have denounced the case against investigative journalist Jose Ruben Zamora as an attack on press freedom.

An award-winning journalist in Guatemala has been convicted on criminal charges in what human rights observers call yet another blow to press freedom and democracy in the Central American country.

José Rubén Zamora, a 66-year-old journalist and newspaper founder, was sentenced to six years in prison for money laundering.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsGuatemala elections: Campaigning begins amid public distrust

Guatemala’s past unearthed: The search for the disappeared

In his final comments before the verdict on Wednesday, Zamora proclaimed his innocence, saying his rights had been violated during the court proceedings.

“They treated us like criminals,” he said of the authorities who pursued the case. “They destroyed evidence.”

In announcing Wednesday’s verdict, the court in Guatemala City claimed Zamora had “harmed the Guatemalan economy”. The public prosecutor’s office had sought a 40-year sentence in the case.

Zamora was acquitted on charges of blackmail and influence peddling.

The journalist, known for exposing corruption in Guatemala, still faces two other criminal cases, one pertaining to signatures on customs documents that did not match. That case was filed just days ahead of the sentencing.

The trial that concluded on Wednesday lasted only 11 sessions – held over 20 days – and has generated widespread concern and condemnation.

“My father is innocent,” the journalist’s son Jose Zamora told Al Jazeera ahead of Wednesday’s conviction.

“The [Guatemalan] state has kidnapped him,” he said. “They have subjected him, within this fabricated case, to a process that has been totally a violation of his due process.”

While the public prosecutor’s office has long maintained the case against Zamora was not about his journalism, critics say the accusations and rapid nature of the trial suggest otherwise.

The case stems from allegations made by Ronald Garcia Navarijo, a former banker accused of corruption, about a deposit of $38,000 that Zamora allegedly asked someone to make on his behalf, as part of a money-laundering scheme.

The Salvadoran newspaper El Faro reported that prosecutors prepared the case against Zamora within 72 hours of receiving the accusation.

Zamora was arrested in July 2022 and kept in pre-trial detention without being able to make his first appearance before the judge for nearly two weeks.

Other irregularities occurred throughout the trial, including Zamora being forced to change lawyers eight times, with at least four of his lawyers facing criminal charges related to the case.

Zamora and the newspaper he founded in 1996, El Periodico, have long worked to expose government misconduct. The paper has played a key part in uncovering alleged corruption in the current administration of President Alejandro Giammattei, publishing over 120 investigations into the government since January 2020.

But El Periodico was forced to close on May 15 amid the fallout from the Zamora case. Its journalists were investigated, and the newsroom had been targeted multiple times in recent years for tax audits.

In a statement, El Periodico’s leadership blamed “persecution” for shuttering the newsroom, as well as “the harassment of our advertisers”. Both Zamora’s case and El Periodico’s closure have raised concerns in the international community.

“They’re using all these tools to basically put [Zamora] out of business,” Carlos Martinez de la Serna, programme director with the US-based Committee to Protect Journalists, told Al Jazeera.

“[This is] sending a very chilling message to journalists – that basically reporting on corruption is a crime,” he said.

Attacks on press freedom

As the case against Zamora comes to a close, another case against journalists from El Periodico is set to begin.

In February, a judge authorised the investigation of nine journalists and columnists from El Periodico on charges of “conspiracy to obstruct justice”, following a request from the lead prosecutor in Zamora’s case. The charges stem from the publishing of stories critical of the legal proceedings against Zamora.

On June 5, the public prosecutor’s office officially requested all the stories published since July by the journalists and columnists in the case.

But the persecution against journalists extends beyond El Periodico’s newsroom, according to observers.

“The press is being harassed at the level of exposure of Jose Ruben Zamora, as well as other low-profile journalists and even community journalists,” Renzo Rosal, a political scientist at Guatemala’s Landivar University, told Al Jazeera.

“Journalists who carry out their work in the interior of the country are victims of the same logic: the logic of persecution, the logic of criminalisation, so that no one investigates anything,” he explained.

Critics say the criminalisation of journalists has become further entrenched since President Giammattei took the oath of office in 2020. A number of renowned journalists have been forced into exile, while others have faced criminal charges and threats.

For example, Anastasia Mejía, a community journalist in Joyabaj, El Quiche, was arrested in 2020 on charges of sedition and arson following her coverage of protests against the mayor of the largely Indigenous municipality in Guatemala’s western highlands. The charges were dropped a year after she was first accused.

In another case from 2022, Carlos Choc, a community journalist from the eastern municipality of El Estor, faced the criminal charge of “instigation to commit a crime” following his coverage of anti-mining protests.

Eventually, Choc was exonerated, but the threats against journalists in El Estor remain, as police continue to intimidate other journalists working in the area.

Rolling back democracy

The verdict in the Zamora case comes within days of Guatemala’s general election on June 25, which has likewise been plagued by controversy.

The country’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal has ruled to exclude three presidential candidates from the race on charges of noncompliance with the country’s election laws. Those disqualifications – which targeted at least one frontrunner – have raised questions about the fairness of the elections and Guatemala’s democratic institutions.

“Today the elections are another indicator of serious democratic erosion,” Rosal says.

Human rights observers have warned that Guatemala has recently seen a sharp rollback of its democracy and its anti-corruption efforts, even beyond the upcoming elections.

Nearly four years ago, the administration of former President Jimmy Morales oversaw the closure of the International Commission Against Impunity (CICIG), a United Nations-backed initiative to address crime and corruption that enjoyed public support of 70 percent.

Giammattei’s administration has continued the trend of dismantling anti-corruption bulwarks, through prosecution of the judges, lawyers and activists involved in those efforts.

Accusations of corruption have also permeated the Guatemalan public prosecutor’s office in recent years. Both Attorney General Maria Consuelo Porras, who was controversially re-elected in May 2022, and Rafael Curruchiche, head of the Office of the Special Prosecutor Against Impunity, have been sanctioned by the United States for corruption and anti-democratic actions.

Critics say Guatemala is currently undergoing its greatest challenge since the country’s return to democracy in 1985, after decades of military rule. Back then, those democratic reforms paved the way for the 1996 peace accords that brought an end to the country’s 36-year-long internal conflict.

But for those who lived through those tumultuous times, Guatemala’s current democratic crisis is a painful setback.

“I struggled for the peace process so that there would be peace in Guatemala,” said Claudia Samayoa, a founder of the Human Rights Defenders Protection Unit in Guatemala (UDEFEGUA). Her organisation grew out of the peace accords and sought to implement its terms in the post-conflict period.

But Samoyoa explained that UDEFEGUA has likewise come under attack, with its leadership facing accusations of influence peddling in relation to Zamora’s case. The organisation has denied those allegations, dismissing them as a smear campaign against its human rights work.

“We have regressed in the exercise of the most basic right of defence,” Samayoa said. “These cases are backwards.”