Singapore’s death row ‘main element of its drug policy’

Dozens of people face hanging for drug offences in Singapore and the city-state has shown no sign it will soften its approach.

Singapore’s use of the death penalty was once again thrust into the global spotlight last month when Tangaraju Suppiah became the first person to be executed in the city-state this year.

His case centred on the trafficking of just more than 1kg of cannabis and made headlines around the world, with some expressing surprise at Singapore’s still strict approach to drugs.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIran executes Swedish-Iranian dual national

Singapore hangs man for trafficking 1kg of cannabis

Surge in executions of drug offenders in 2022, more on death row

Last year, 11 men are known to have been hanged by the state. Singapore’s prison authorities do not report details of these cases, so information is gathered via families of prisoners or campaign groups.

One such organisation, the Transformative Justice Collective (TJC), believes that there are currently 54 people on death row in Singapore, with all but three of them sentenced to death for drug-related offences.

“It shows that the Singapore government is very committed to the death penalty being the main element of its drug policy”, said Sara Kowal, vice president of the Capital Punishment Justice Project in Australia.

Human rights experts from the United Nations have also pointed to the number of death row prisoners who are from ethnic minorities, saying: “a disproportionate number of minority persons were being sentenced to the mandatory death penalty in Singapore”.

Research from the TJC found that almost two-thirds of the offenders handed the death penalty for drug offences between 2010 and 2021 were of Malay ethnicity, a minority in the city-state.

Al Jazeera contacted Singapore’s Ministry of Home Affairs for comment, but they did not respond.

They have said previously that the country’s “criminal laws and procedures apply equally to all, regardless of background – race, nationality, education level or financial status”.

The Ministry has also defended the use of the death penalty, arguing that capital punishment is “an essential component of Singapore’s criminal justice system and has been effective in keeping Singapore safe and secure”.

Despite international pressure, the city-state has shown little appetite for softening its tough drugs laws, and campaigners this week said they had been alerted to the hanging — scheduled for May 17 — of an inmate convicted of trafficking cannabis.

The UN says that, if retained, the death penalty should only be used for the most serious crime and that drug offences do not reach that threshold.

But the latest report on the use of the death penalty in 2022 has found that the number of global executions for drug-related offences more than doubled last year compared with 2021.

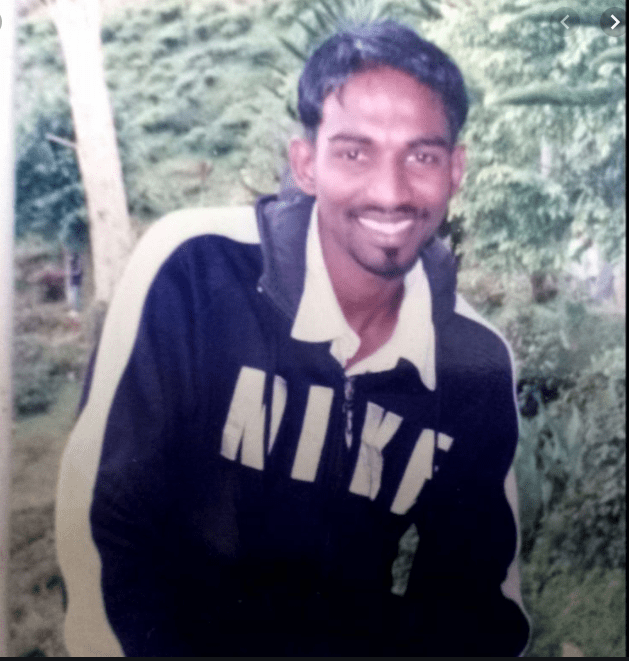

The prisoners profiled below are some of those living on death row in Singapore after being found guilty of drug charges.

Pannir Selvam Pranthaman

Pannir was 27 years old when he was arrested in 2014 at the Woodlands border checkpoint in the island’s north, which separates Malaysia and Singapore.

Inspection officers found small bags of drugs strapped to his groin and stuffed into the backseat compartment of his motorbike.

He was arrested and charged with smuggling 51g of diamorphine (heroin). Under Singapore law, anybody found with more than 2g of diamorphine is presumed to have that drug for the purposes of trafficking.

Three years after his arrest, Pannir was sentenced to death.

Pannir, a musician from the northwestern Malaysian city of Ipoh, has fought continuously for his execution to be halted, supported by his family who have set up a website and started a petition for his freedom.

They have also shared the songs and poems Pannir has written while on death row in the hope of raising awareness of his plight.

In May 2019, their worst fears were realised when Pannir was given a date for his execution.

“Before this, he had never been accused or convicted of any crime. The news of his death sentence came as a complete shock to our family, and devastated us,” Pannir’s family wrote in the petition.

Pannir filed a last-ditch criminal motion to try and stay alive. He was set to represent himself in court, but two lawyers unexpectedly agreed to take on his case.

On the eve of his execution, Pannir was granted a reprieve by the Court of Appeal after he said he planned a legal challenge to the president’s rejection of his appeal for clemency.

His family say his experience on death row in Changi Prison has transformed him, that he feels “deep remorse” for his actions, and that he now wants the chance to educate others on the risks of drug abuse.

For now, Pannir’s fate remains in the hands of the legal system. He is part of a group civil litigation suit against the Singapore Prison Service over private letters being released to the Attorney-General’s Chambers.

That case was recently adjourned for 10 weeks, granting Pannir more time.

Syed Suhail bin Syed Zin

Syed Suhail bin Syed Zin was arrested in Singapore in August 2011. He was 35 at the time.

The Singaporean was convicted in 2015 for possessing 38g of diamorphine for trafficking. He was sentenced to death a year later.

Like Pannir, Syed has previously been assigned a date for his hanging. He was also given a stay of execution with just a day to spare.

He learned of the date of his execution in September 2020, when Singapore’s borders were closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It meant many of Syed’s close relatives in Malaysia were unable to visit him. He reflected on this in a letter to his lawyer just three days before he was scheduled to hang.

“The insensitivity and the entirely new level of cruelty that decision makers have decided to unleash, is felt more so by my loved ones, even though it is directed at me”, he wrote.

Syed’s sister, Sharmila, shared another letter that she had received from her brother in April 2022.

“The harshness and cruelty that some have claimed is just, is not. Two wrongs do not make a right. In the end, there is only a legacy of bloodshed that posterity may not even want on their hands anymore,” he wrote.

Syed is now part of the same civil litigation as Pannir. His execution has also been stayed as he awaits the outcome of that case.

Saridewi Djamani

Saridewi Djamani is one of only two women understood to be on death row, according to the TJC.

“Because we are not as closely connected to the families of women on death row, and because the women are held separately from the men, we don’t get a lot of information coming to us about their conditions and treatment”, Kirsten Han, a Singaporean who campaigns against the death penalty, told Al Jazeera.

A drug user, Saridewi was 40 years old when she was sentenced to death in 2018.

She was charged with possessing just more than 1kg of “powdery substance”, which included 30g of diamorphine, for the purpose of trafficking.

Her case centres around events that took place at her apartment in Singapore in June 2016.

It was there that prosecutors say she met a Malaysian man who gave her a plastic bag of drugs in exchange for envelopes which contained at least 10,050 Singapore dollars ($7,526) in cash. The court documents show the man had an additional envelope containing 5,500 Singapore dollars ($4,119) when he was caught.

Police officers arrived at Saridewi’s flat shortly after. The investigators alleged that when she heard them arriving, she immediately started throwing the drugs out of her kitchen window.

It was only afterwards that she let the officers into the apartment where they arrested her following a search of the flat and its surroundings, they said.

Local media reported that Saridewi claimed she was stocking up on heroin for Ramadan, the Muslim fasting month, because she thought she might need to take more of the drug.

The court dismissed her defence and court documents show that a further appeal was unsuccessful.

Little else is known about Saridewi, and none of her family have come forward to publicise her case.

Datchinamurthy Kataiah

Datchinamurthy was 25 when he was caught with almost 45g of diamorphine at the Woodlands Checkpoint.

With his three sisters, he grew up in Johor Bahru, a Malaysian border town home to many who commute daily to Singapore for work. He was heading from there into Singapore when he was arrested.

Datchinamurthy was sentenced to death in 2015 and failed in an appeal a year later. In his defence, Datchinamurthy claimed he thought the drugs were Chinese medicines.

In April 2022, he was notified of his impending execution. Datchinamurthy was set to be hanged just two days after fellow Malaysian Nagaenthran Dharmalingam was executed.

Nagaenthran’s case had sparked international condemnation of Singapore, after he was found to have an IQ of 69, suggesting an intellectual disability.

On the eve of his scheduled execution, Datchinamurthy had to represent himself during an appeal hearing, as his family were unable to secure legal counsel.

Despite this, Datchinamurthy won. He is also part of the civil litigation case along with Syed and Pannir. The court ruled that he should be granted a stay of execution while that case makes its way through the courts.

Just days before that dramatic last-minute appeal, words from Datchinamurthy’s mother were read out at a rare protest against the death penalty in Singapore.

“These are our children, birthed from our bodies, and you won’t let us touch them”, read TJC’s Kokila Annamalai on behalf of Lakshmi Amma.

Her words reference how families can only see relatives on death row behind a glass panel, with no contact allowed.

Masoud Rahimi Mehrzad

Masoud Rahimi Mehrzad was arrested for drug offences in May 2010. He was 20 at the time — young enough to still be serving compulsory National Service in Singapore.

Driving a rented sports car to Bishan MRT station in the heart of the island, he was tailed by police officers.

At the station, Masoud met a Malaysian man who got out of his own car and climbed into Masoud’s Mazda RX8. Shortly afterwards, the pair parted ways but both were arrested later at separate locations.

Officers searched Masoud’s car and found drugs, some of which were in a bag branded with Mickey Mouse. He was charged with the possession of 31g of diamorphine for the purposes of trafficking and faced the same charge for 77g of methamphetamine (crystal meth).

According to court documents, Masoud told police that he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety.

Masoud also claimed that the drugs were planted in his car by an illegal money-lending syndicate after he told them he no longer wanted to work for them.

The High Court rejected this defence and Masoud was convicted.

Like many prisoners on death row, little more is known about his situation.

In 2021, Masoud’s sister signed a public letter calling on Singapore’s President Halimah Yacob to abolish the death penalty.

A year later, he was among a group of death row inmates trying to find out more about whether their private letters had been passed to the Attorney General. Unlike Pannir, Masoud’s case was dismissed.