Differences remain as talks to protect high seas enter final day

The High Seas Treaty has been years in the making, but disagreements remain over issues including benefit sharing.

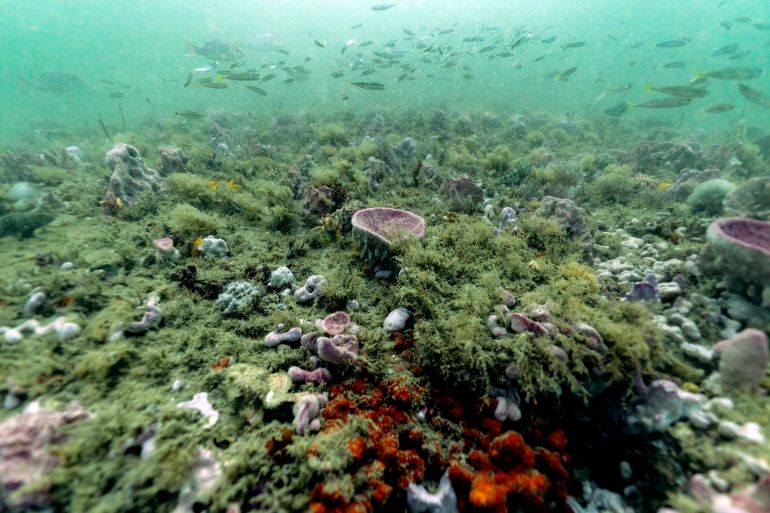

UN member states are wrangling over the terms of a treaty to protect the high seas, a rich and largely unexplored ecosystem that covers nearly half the planet.

After more than 15 years of informal and then formal talks, negotiators on Friday were coming to the end of two more weeks of discussions, the third “final” session in less than a year.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsBalloon ‘panic’ intensifies push against China in Washington

UN ocean treaty talks: ‘Life support system of our planet’

The High Seas Treaty would ensure that governments meet their commitment to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and ocean by 2030, as agreed in Montreal in December.

But before Friday’s scheduled end of discussions, longstanding disputes remained unresolved.

They included the procedure for creating marine protected areas, the model for environmental impact studies of planned activities on the high seas, and the sharing of potential benefits of newly discovered marine resources.

While more is known about the surface of Mars than the depths of the high seas, valuable resources are known to lie kilometres under the surface.

Hydrothermal vents – or fissures on the seabed – are rich in minerals necessary for the batteries that are essential in the age of renewable energy, while marine genetic resources are thought to be precious sources of information that could unlock the secrets of life.

Environmentalists have called for the treaty to establish ocean sanctuaries to protect high sea ecosystems, which create half the oxygen humans breathe and limit global warming by absorbing much of the carbon dioxide emitted by human activities.

North-South ‘equity’

The high seas fall under the jurisdiction of no country, as countries’ exclusive economic zones extend up to 200 nautical miles (370 kilometres) from coastlines.

“Who owns the high seas is the question at the moment,” Laura Meller, Grenpeace campaigner, told Al Jazeera. “The treaty is our biggest opportunity to put conservation and equity at the heart of how we look after our oceans after decades of mismanagement and exploitation.”

Developing countries without the means to afford costly research have said that they fear being left behind, while others make profits from the commercialisation of potential substances discovered in international waters.

Steve Widdicombe, a marine ecologist at Plymouth Marine Laboratory, told Al Jazeera that researchers were “just starting to peer into the murky depths and understand what is there”.

Widdicombe called for prudence, “as our ability to impact on a system far away currently outstrips our evidence or knowledge of what exist there.”

At a short plenary session Friday morning, the conference’s presidency urged delegates to be “flexible as much as you can” in the “final push” that could run late into Saturday’s early hours.

Observers were hoping for a political boost from the Our Ocean conference taking place in parallel in Panama, where many government officials were discussing the protection and sustainable use of the oceans.

If an agreement were to be reached, it remained to be seen whether the compromises made would result in a text robust enough to protect oceans effectively.