‘Ambiguous by design’: What’s in the Kosovo-Serbia deal?

Proposed settlement is focused on conflict avoidance rather than achieving lasting peace, analysts say.

A peace deal being pushed by powerful Western nations to resolve tensions between Serbia and Kosovo fails to address mutual recognition, which essentially means it would fail to achieve real progress, analysts have told Al Jazeera.

Among the provisions in the proposal touted by France, Germany and the United States, Serbia would not explicitly recognise Kosovo’s independence but would have to stop lobbying against its membership in international bodies, such as the United Nations.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAlbin Kurti: Can Kosovo bond with its ethnic Serbs?

How fragile is the peace between Serbs and Kosovars?

Kosovo-Serbia tensions: Mood on the ground, possible scenarios

The two neighbours would also have to open representative offices in their capitals under the plan, which was first leaked in November and then subsequently announced by Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic. As a concession, the Serb community in Kosovo would be granted self-governance.

Kosovo declared independence in 2008, a decade after a war that saw an Albanian Kosovar uprising against Belgrade’s oppressive rule.

Serbia does not recognise Kosovo’s independence. Neither do Russia, China and five European Union countries – Spain, Slovakia, Cyprus, Romania and Greece, which have halted its path to EU membership. Russia, Serbia’s historical ally, has vetoed Kosovo’s membership at the United Nations.

For more than a decade, Belgrade and Pristina have been holding EU-mediated normalisation talks with the goal of joining the bloc.

Gezim Visoka, associate professor of peace and conflict studies at Dublin City University, told Al Jazeera the agreement seems to be “designed more for conflict avoidance rather than building a lasting peace between Kosovo and Serbia”.

Provisions stipulated in the proposal “continue to carry on ambiguities” regarding mutual recognition, Visoka said.

The agreement does not address the five EU member states that have yet to change their position on Kosovo, and there is no clarity on Kosovo’s path to joining international bodies, such as the UN, he said.

Kurt Bassuener, senior associate at the Democratization Policy Council, a Berlin-based think tank, told Al Jazeera the deal is “ambiguous by design”.

“It’s certainly not a recognition from a Kosovo perspective of trying to move forward to full recognition and ability to join clubs in the international community,” Bassuener said.

Another Republika Srpska?

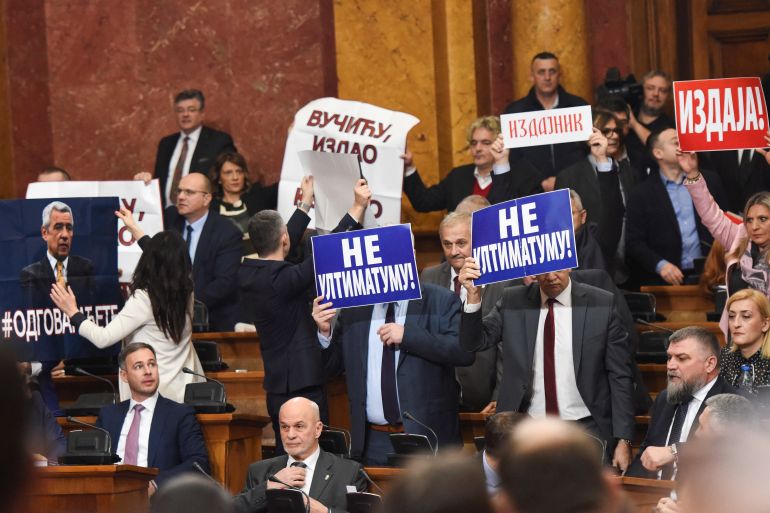

In the Serbian parliament last week, a brawl erupted between opposition and ruling party deputies during Vucic’s speech.

Opposition lawmakers held signs saying “betrayal” and “capitulation” as they interpreted the deal as de-facto recognition of Kosovo’s independence.

But Boban Bogdanovic, founder of the Serb opposition bloc from Kosovo, told Al Jazeera he “fully supports” the deal because it is a “responsible approach” to solving problems between the two countries.

“The agreement guarantees rights to the Serbian community from the international community,” he said.

The 100,000 Serbs in Kosovo are the nation’s largest ethnic minority. About half live in northern Kosovo near the Serbian border, where they form the majority of the population. They do not recognise the government in Pristina there and have their own administrative and health systems.

International officials have stressed the need for Kosovo to establish an Association of Serb-Majority Municipalities (ASM) in northern Kosovo.

Forming the ASM was stipulated in an EU-mediated 2013 agreement to normalise relations between Serbia and Kosovo, but the Constitutional Court of Kosovo ruled against it, declaring that it was not inclusive of other ethnicities and objecting to the ASM’s executive powers.

Many Albanians, including Prime Minister Albin Kurti, have expressed concern that it would only create another mini-state or another Republika Srpska, the Serb-run entity in Bosnia and Herzegovina, formed as part of the Dayton peace agreement.

The peace accord, signed in 1995, ended the war in Bosnia, but it was not meant to be a lasting solution. Twenty-seven years later, there is a growing threat of the Republika Srpska’s secession to join Serbia, which is pushed by its president, Milorad Dodik.

“A mono-ethnic association in a multi-ethnic Kosovo is not possible,” Kurti told journalists last week.

Last week, Derek Chollet, US counselor of the Department of State, and Gabriel Escobar, US deputy assistant secretary of state, made assurances that the ASM would not be mono-ethnic and wrote in a joint op-ed for a Kosovo news website that they “strongly oppose any form of entity that resembles Republika Srpska”.

The ASM would not add a new layer of executive and legislative power in Kosovo, they wrote.

Bogdanovic said there is no reason to fear another Republika Srpska forming in Kosovo. Establishing an ASM would provide an “opportunity to cooperate with mother Serbia and, most important of all, harmonise relations with Pristina”, he argued.

“The [ASM] cannot have territorial autonomy … and will be formed in accordance with the constitution and laws of Kosovo, not Serbia,” he said.

But Visoka said an ASM is “unlikely” to resolve the conflict.

“It risks laying the foundations for more troubles that fragment rather than unite ethnic communities in Kosovo,” Visoka said.

“It makes sense to explore creative and constitutionally permittable mechanisms for accommodating minority rights only when there is mutual recognition and interstate normalisation between Kosovo and Serbia,” he said.

“We have tried in the past the creation of minority protection mechanisms without mutual recognition and they have not been as effective as desired precisely because they lack clarity on the question of Kosovo’s recognition,” Visoka argued.

Western governments have a track record of unfulfilled promises towards Kosovo, he added, and diplomatic assurances and guarantees will not be enough to persuade the government to establish an ASM.

‘Not clear what the goal of the West is’

Tensions in north Kosovo have risen recently. In December, ethnic Serbs set up roadblocks to protest the arrest of a policeman suspected of being involved in attacks against ethnic Albanian police officers.

After the barricades went up, Kosovar police and international peacekeepers were shot at.

In November, hundreds of Serb officials – including police officers, judges, mayors and members of parliament – resigned from state institutions en masse to protest against the decision to ban Serbs from using Belgrade-issued licence plates on their cars, a decision that Pristina later scrapped.

Meanwhile, Belgrade has encouraged ethnic Serbs in Kosovo to defy Pristina’s rules.

For Bassuener, the ASM “is designed precisely to do what Russia attempted to do with Ukraine between 2014 and a year ago, which is to limit Kosovo’s ability to exercise sovereignty even within its own territory let alone on the international stage”.

“For the West, it’s just about saying we got something that we can call progress and we quieted it down,” Bassuener said.

“I think Vucic is hoping to maintain his ability to continue this formula of geopolitical arbitrage where he extracts maximally from all stewards while giving away as little as possible,” he said. “I don’t think anybody is really being sincere or honest about there being some goals in this process, except for Kosovo. I think not just the prime minister but also the president, they’ve been very clear about their overarching goals.”